16 Charts that Changed the Way We Looked at America’s Schools in 2021

By Kevin Mahnken | December 15, 2021

If 2020 was a year unlike any other, 2021 was…the same, only more so.

Schools in thousands of districts remained closed for months at a time, forcing teachers and students to make the best of remote learning modalities that were adopted under emergency conditions. Bitter partisan disagreements erupted around districts’ COVID mitigation efforts, then spread to history curricula, youth sports, and school board races. It was another year, in short, lived beneath the cloud of the greatest disruption to K-12 schools in our history.

But 2021 was also the year when the pandemic’s mysteries began to be answered. Ample research has shown that learning loss — however contested the idea is in ever-raging education policy debates — is real, and its primary victims are the students who were already behind before the pandemic began. The student exodus from traditional public schools has been tabulated, and the surge in homeschooling and charter school enrollment is becoming clear. And research efforts have been launched to measure COVID-19’s influence on everything from fertility rates to child obesity.

In the meantime, researchers are also telling us more about some of the perennial questions of education policy: Has Common Core actually changed instruction? What about right-to-work laws? And what was the long-term legacy of redlining on schools?

Here, laid out in charts, maps, and tables, are 16 discoveries that changed how we think about schools in 2021.

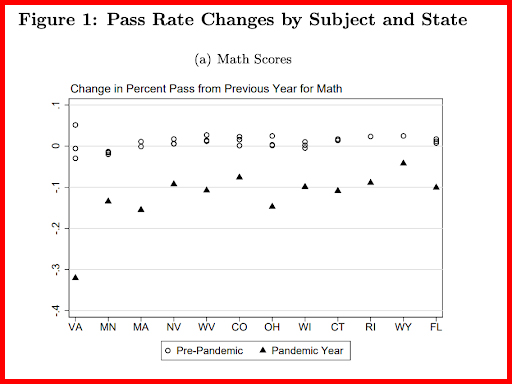

Serious learning loss followed remote schooling

The academic effects of the transition to remote schooling were feared, but largely ambiguous last year. With more data available in 2021, the picture is getting both clearer and more concerning.

Perhaps the most alarming findings come from a recent working paper by economist Emily Oster and several co-authors, which examined standardized test scores from this spring for children between grades three and eight. Across 12 states, exam pass rates declined significantly (an average of 14.2 percentage points in math and 6.3 points in English) compared with the year before the pandemic; but in school districts that chose to offer full-time, in-person classes, those losses were significantly reduced. Unfortunately, areas with lower scores and higher shares of African American students provided less in-person learning, and the impact of virtual schooling on reading scores was larger in districts serving a majority of non-white students.

Among the major predictors of whether a school opened its doors or stayed remote during the pandemic was partisanship. That first became clear last fall, when multiple studies showed that school districts’ reopening decisions were much less correlated with local COVID infection rates than with local voters’ choice of Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. Those patterns persisted throughout the 2020-21 school year, with data from the school calendar aggregator Burbio indicating that schools in Trump-voting states offered twice as much in-person school on average than those in states that favored Joe Biden (872 hours versus 440 hours).

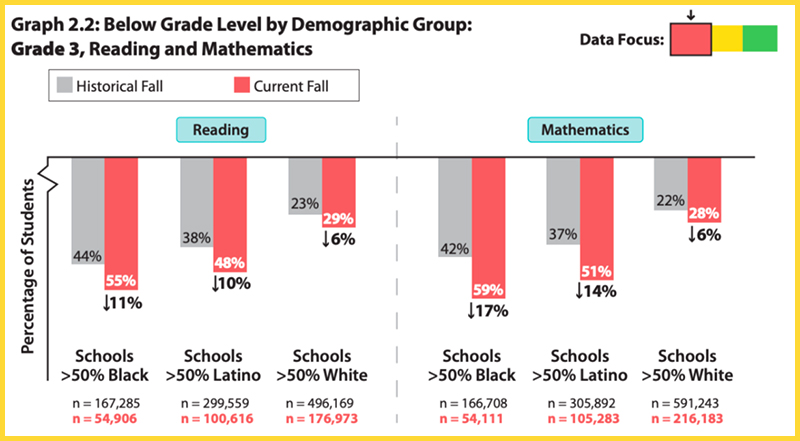

Finally, since last spring, educators have warned that COVID-19 would pose greater dangers to disadvantaged students. Those suspicions are supported not just by Oster’s study, but also evidence from Curriculum Associates, the group behind the online i-Ready assessment. Data released in November showed that third graders in less affluent districts, as well as those predominantly enrolling African American and Hispanic students, were much more likely to score significantly below grade-level in math and reading than they were before the pandemic. The scoring dips were considerably smaller in whiter and better-off areas.

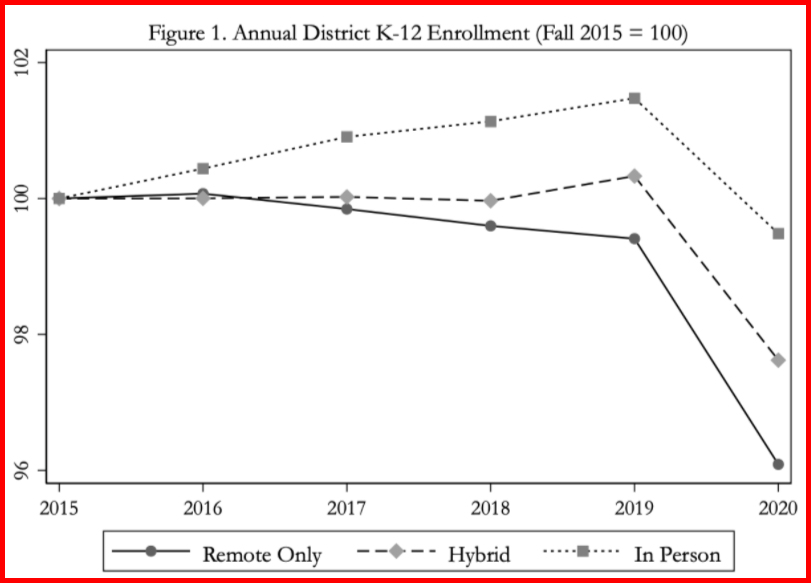

Virtual switch led to drop in school enrollment

As the pandemic’s academic consequences were becoming known this year, school officials were awakening to a related phenomenon. Families, especially those with young children, were moving away from public schools. Numbers revealed by the National Center for Education Statistics this summer showed that America’s total K-12 enrollment dropped by roughly 3 percent — or 1.5 million students — during the 2020-21 academic year. Declines in Vermont, Mississippi, and Puerto Rico were over 5 percent.

Studying the development across hundreds of school districts, researchers at Stanford pointed to a contributing factor: the switch to online learning. In a working paper circulated in August, economist Thomas Dee and his co-authors asserted that roughly 300,000 students left schools directly in response to the transition to all-remote classes. The departure was overwhelmingly driven by families with children in kindergarten or elementary school, with higher grade levels essentially unaffected.

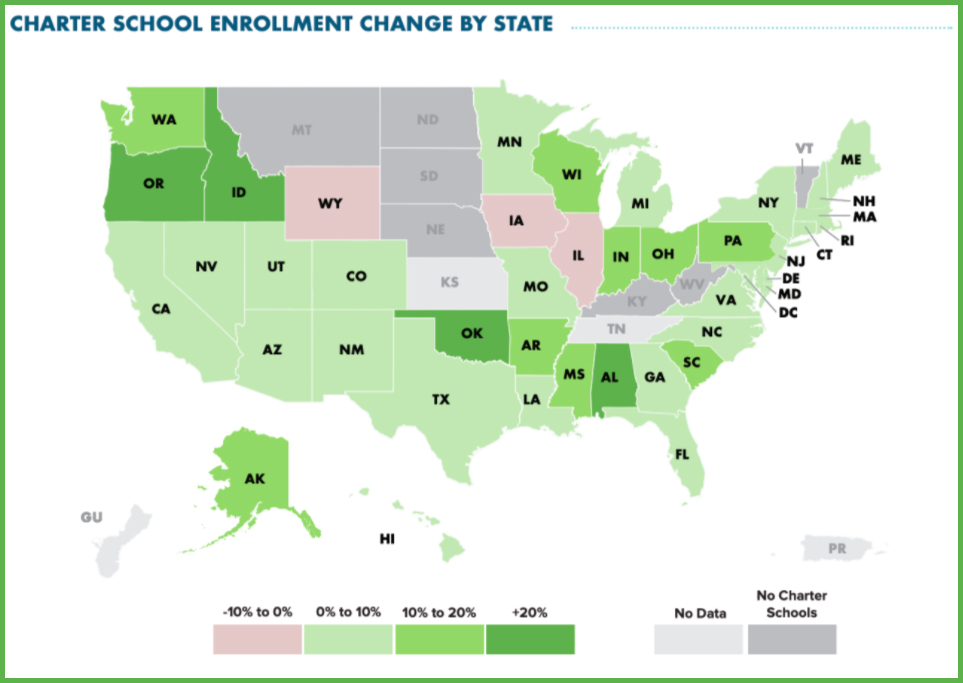

Families headed to charter schools

The exodus of students from traditional school districts was eventually felt in a variety of other educational settings. In cities like Boston and San Diego, Catholic schools — which had seen enrollment plummet in the early days of COVID — saw huge new demand for seats as fall got underway. At the same time, the U.S. Census Bureau reported a doubling of the percentage of households opting to homeschool their kids.

Meanwhile, American charter schools experienced their own surge in interest. According to information collected by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, the sector took in 240,000 new students during the 2020-21 school year — more growth than had occurred over the preceding six years. That included ten states that saw charter enrollment expand by more than 15 percent.

As the Alliance’s president, Nina Rees, told The 74’s Linda Jacobson, the novel coronavirus “forced families to rethink where and how education could be delivered to their children. And now that they know what’s available, why would they go back to an option that never really worked for them in the first place?”

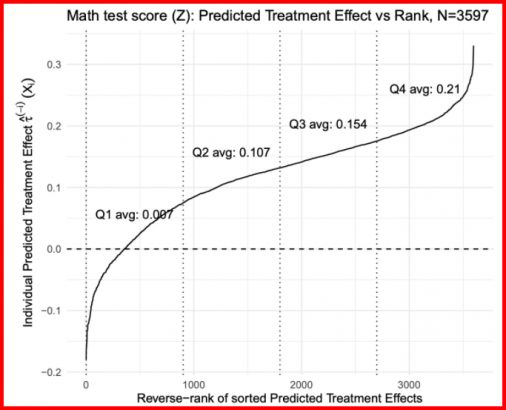

More evidence points to promise of tutoring

Even before COVID, a groundswell of expert support was building behind the idea of using intensive tutoring to bolster the achievement of struggling students. A well-publicized 2020 meta-analysis of nearly 100 tutoring studies demonstrated the promise of one-on-one or small-group tutoring, even suggesting that family members or volunteers could make a big difference in kids’ learning outcomes when education professionals weren’t available.

As if that evidence weren’t enough, a compelling new study was released in March to strengthen the case further. An analysis conducted by an array of well-known scholars showed that Saga Education’s tutoring initiative — originally pioneered in Boston’s high-performing network of Match charter schools before being implemented on a wide scale in Chicago — led students to achieve enormous growth in math scores and course grades over several years. Randomly selected Chicago high schoolers who received an hour of tutoring each day experienced double the growth of an average student over the course of a year. The huge size of the student sample (5,000 students) also dispels fears that the impressive gains might not be scalable.

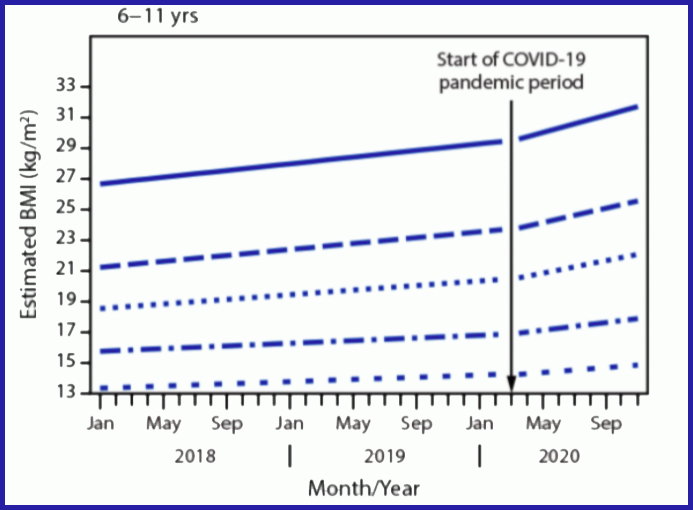

The pandemic made kids more overweight

In addition to the historic challenges it presented to schools and learning, the pandemic represented an ordeal of inactivity for tens of millions of young people. Many, cut off from friends and consigned to learning from the couch, moved around considerably less and saw their diets significantly altered during the school day.

The mass transition to a sedentary childhood held unmistakable repercussions for their health. Multiple studies, including one from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have now shown that rates of obesity increased dramatically during the year following school closures. In a sample of over 400,000 school-aged patients, the CDC’s researchers found, body mass index rose at almost double the rate that it did in 2019. The changes were most prevalent in younger children, as well as those who were already overweight or obese.

Achievement was sinking long before the pandemic

The pandemic-era revelation that aroused the most concern this year actually had nothing to do with COVID-19. Instead, the remarkable decline in long-term scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — referred to as “the nation’s report card” — were measured in late 2019 and early 2020, before the public health crisis forced schools around the country to shut their doors.

The scores, made public by NCES this fall, represent the first time in the history of the “Long-Term Trends” assessment that scores actually dropped between testing rounds. While prior NAEP releases, including discouraging science results from earlier this year, had pointed to a disconcerting divergence between higher- and lower-performing students, they didn’t prepare experts for the scale of the drops measured since 2012: three points in math and five points in reading for 13-year-olds, and no progress made on either subject by nine-year-olds.

As the final assessment of American achievement taken before the arrival of COVID, the scores offer a grim accounting of the K-12 status quo. As George Bohrnstedt, a senior vice president and institute fellow at the American Institutes for Research, told The 74’s Kevin Mahnken, “It’s really a matter for national concern, this high percentage of students who are not reaching even what I think we’d consider the lowest levels of proficiency.”

Little evidence of Common Core’s impact

Though it can be a little hard to recapture the enmity a decade later, the emergence of Common Core during the Obama administration was the most contentious question in education policy for several years. Though the hundreds of pages of content standards were developed by non-partisan sources and voluntarily adopted by states, many parents and politicians believed they were an encroachment on local control of schools and a possible Trojan horse for liberal politics. Meanwhile, proponents argued that Common Core held the promise of dramatically improving instruction and setting more kids on the path to college.

But after more than a decade of development and implementation, several studies have suggested that the ambitious reform actually hasn’t made much of an impact on how kids learn, period. Most recently, research published by the American Education Research Association in April found that the standards led to only modest growth in math scores in states that adopted them early — and even those benefits were driven mostly by well-off students who were already more likely to be doing well academically.

The meager results, combined with similar findings in other recent studies, may raise the question of how much Common Core actually ended up changing instruction in states where it was adopted.

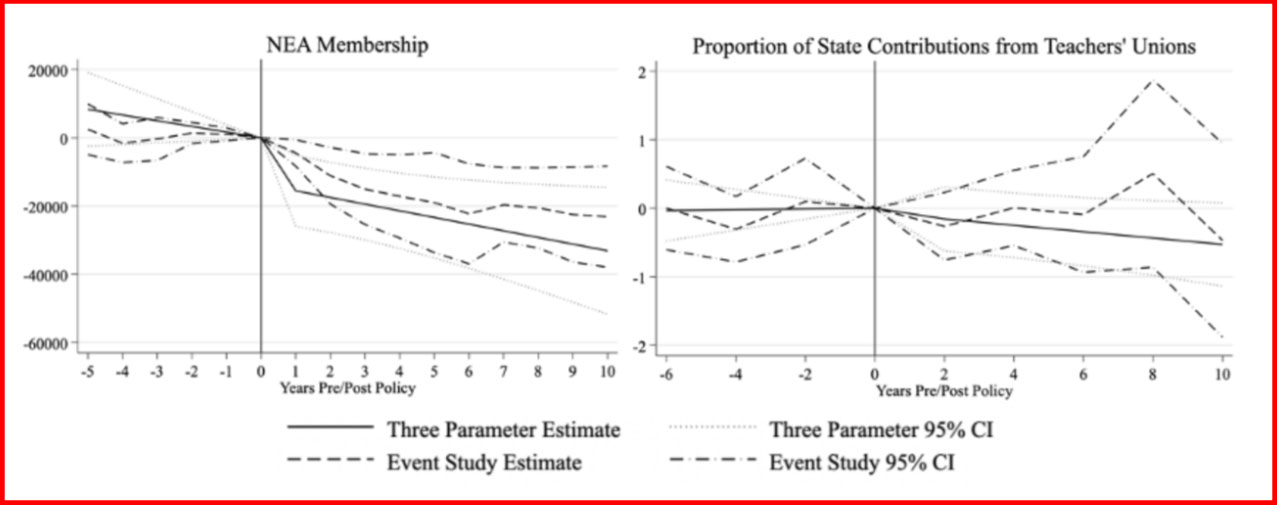

Right-to-work shows no academic benefits

Another massive mid-2010s edu-controversy was embodied in two cases focusing on organized labor: Vergara v. California and Janus v. AFSCME, the latter of which forbade teachers’ unions from collecting mandatory “agency fees” from non-members in lieu of dues. When the Supreme Court ruled, 5-4, against the practice, it was theorized that the decision would effectively turn the entire country into a right-to-work zone for public-sector employees.

A working paper released in February investigated what the effects of that switch might be by studying the academic and political effects of right-to-work laws. Examining multiple outcomes in the aftermath of right-to-work policies being enacted across seven states since 1990, Brown University researcher Melissa Arnold Lyon found that — as advertised — the laws weakened union strength (as measured by membership and contributions). But there was no evidence that they led to the introduction of new education reforms, such as merit pay or charter schools. And the apparent effects of the laws on student achievement, as measured by NAEP scores, were negligible.

More research will be needed to assess the wide-ranging impact of Janus on labor influence, school expenditures, and even election results. For the moment, however, policies challenging teachers’ unions don’t seem correlated with big changes to education policy or K-12 learning.

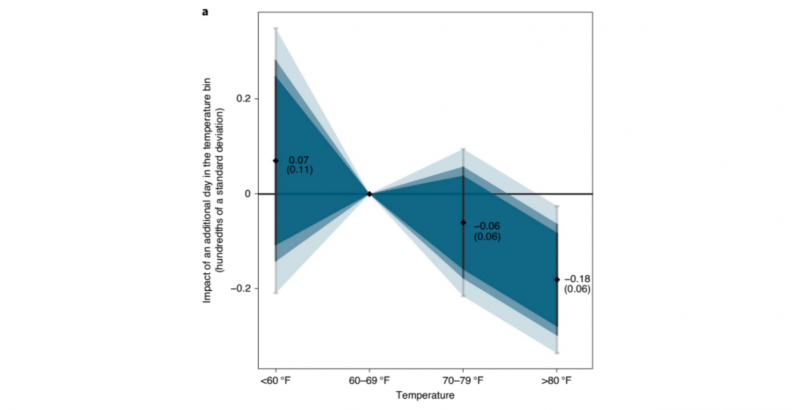

Classroom heat can seriously hinder learning

For years, advocates have complained of the environmental learning challenges faced by some under-resourced schools, including the absence of air conditioning in some states where late-summer heat can regularly disrupt the first weeks of the school year. Calls for better-managed school facilities grew as the threat of COVID forced educational leaders to think about how to better ventilate classrooms.

In an intriguing article published in January, researchers from UCLA, Stanford, and Boston University gathered student achievement data from nearly 60 countries and over 12,000 U.S. school districts, examining standardized test scores against “detailed weather and academic calendar information” to examine the effects of increased heat on learning. The answer: The more days students were exposed to temperatures over 80 degrees, the worse they performed on the PISA, an international exam testing 15-year-olds in math, reading, and science. Given the relatively poorer academic performance often detected in tropical countries and southern U.S. states, the results may partially explain why academic achievement can vary so much by region.

Long-term gains from ethnic studies

This fall, California became the first state to require students to enroll in a semester-long ethnic studies class in order to graduate high school (the mandate will not take effect until the end of the 2020s, though all schools will offer the classes by 2025). The state has been pushing in this direction for years, unveiling a model curriculum this spring after a lengthy public comment period.

At the same time the proposal was being considered, research into the academic effects of ethnic studies instruction has been ongoing. One study — published in September and conducted by academics at Stanford, the University of California, Irvine, and the University of Massachusetts — found that San Francisco students who were assigned to take an ethnic studies course in ninth grade were less likely to be absent from school, more likely to graduate, and more likely to enroll in college. The pilot program under examination enrolled less than 200 students, raising questions about whether its benefits can be scaled up; but the authors were encouraged by the persistence of the gains that students made over several years.

COVID ‘birth dearth’ underway

Fertility rates have been consistently dropping in the United States since the Great Recession. It’s a long-term development with untold significance for American society, especially concerning population growth and the strength of the economy. But it’s already changing the face of education, with school districts increasingly confronting financial shortfalls and debating whether to close or consolidate schools that enroll shrinking numbers of kids.

If anyone hoped that a year of young people trapped inside their homes might turn things around, they were sorely mistaken. Data released this spring by the CDC made it clear that childbearing only declined further during 2020, with total births falling 4 percent to their lowest level since 1979. In all, fertility dipped for women across all racial, ethnic, and age groups.

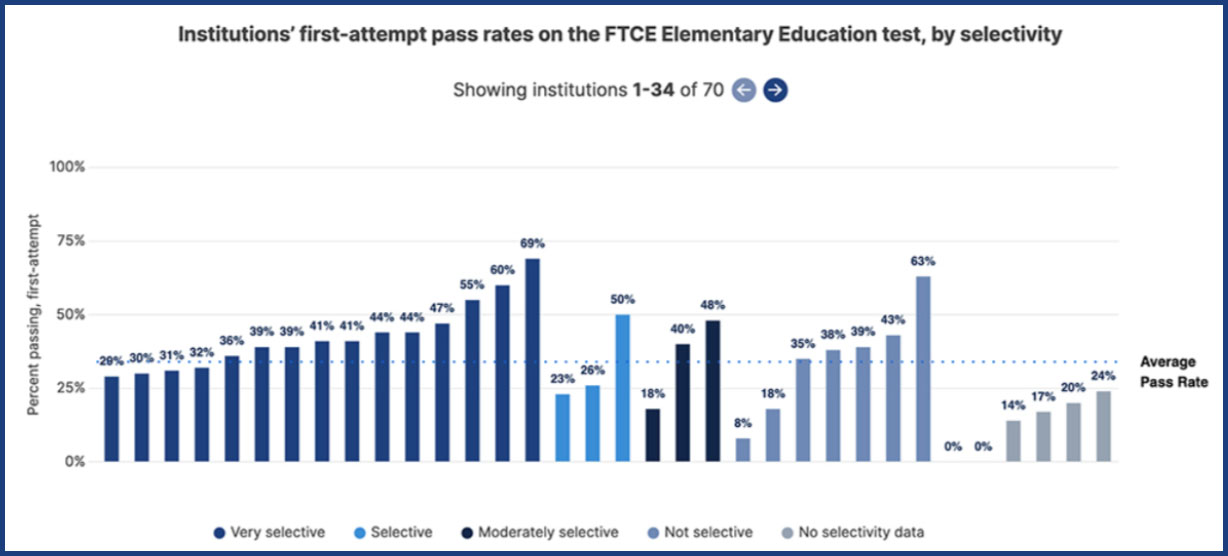

Teaching candidates fail licensure exams in huge numbers

It’s a well-known problem that educators and state officials rarely talk about: Teaching candidates, even after years spent in graduate courses and student-teaching programs, often struggle to pass their licensure exams. Just months away from stepping into a classroom, many have to shell out money they don’t have in order to succeed on a second and third attempt; some, discouraged, walk away from the profession entirely.

In an effort to shine a light on the issue, the National Center for Teacher Quality — a reform-oriented advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. — published institution-level pass rates for teacher preparation programs in 38 states in a report released this summer. The results are startling: Twenty-nine percent of all programs reported that less than half of their participants passed their state’s licensure exam on the first try between 2015 and 2018; the average “best-attempt” pass rate (i.e., the frequency with which test-takers ever pass) was just 83 percent.

“The whole point is, you’re supposed to be preparing candidates for licensure,” NCTQ president Kate Walsh told The 74’s Kevin Mahnken. “And nobody points out to the kids going into these programs, ‘Your chances of getting a license at this institution are nil.’”

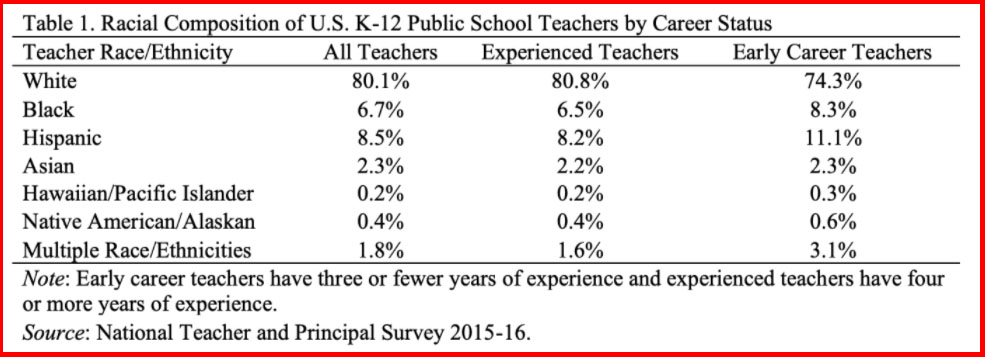

Burden of teacher layoffs falls heavily on disadvantaged students

As COVID shut down the economy and decimated jobs by the millions in the spring of 2020, many warned of the havoc that could be visited on schools by a protracted economic downturn. Pointing to research that followed in the wake of the Great Recession, some experts warned that slower growth and diminished local tax revenues could lead to a cascade of negative effects on schools, including cuts to teaching jobs.

Thanks to the historic infusion of federal funding that flowed to districts over the last two years, the theorized financial crunch on districts was averted. But a recently released policy brief from Brown scholars Matthew Kraft and Joshua Bleiberg offers a persuasive account of the educational pitfalls that can accompany sudden teacher layoffs.

Surveying the existing research, the authors highlighted the particular ramifications of teacher firings on educational equity. Ultimately, they conclude, poor and nonwhite students feel the impact disproportionately because their schools are more likely to rely heavily on K-12 aid provided by the state; since that revenue is more sensitive to recessions, disadvantaged students are generally more exposed to deeper budget cuts and staff shortages during fiscal contractions. That phenomenon is magnified by the fact that the schools serving those students are more likely to be staffed by early-career teachers, who are often the first to be targeted by layoffs.

“The Great Recession caused the largest labor force decline in the history of U.S. public schools until the COVID-19 pandemic,” Kraft and Bleiberg write. “Although the immediate future looks brighter than many analysts predicted at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the long-term prospects of potential teacher layoffs remain.”

Mexican-American integration changed lives…

Brown v. Board of Education is one of the most celebrated triumphs in the history of American jurisprudence, a milestone for both the civil rights movement and the struggle to ensure that every student receives a worthy education. But another federal court case, transformative if comparatively unrecognized, stands in its shadow: Mendez v. Westminster, a landmark 1947 lawsuit that rolled back segregation of Mexican-American students in California.

With the release this summer of a working paper on the litigation’s long-term impact, Mendez will hopefully begin to receive the attention it deserves. The study, authored by economists at the University of Colorado Boulder and Texas A&M, finds that desegregation led to a sizable increase in educational attainment — 1.9 years on average — for Mexican-American students born after the case versus those born 10-20 years before.

…and so did redlining

But long-gone policies that originated in racial prejudice can leave a modern-day impact on schools as well. In particular, the strong link between real estate markets, property values, wealth, and school assignment has often kept non-white families from accessing high-quality schools and led to school funding disparities that further disadvantage poor students.

Perhaps the foremost case is that of redlining, which denied home loans and other financial services to the predominantly non-white residents of many inner-city neighborhoods. In a working paper circulated this year, two Harvard doctoral candidates traced the latter-day legacy of the federally sanctioned discrimination on K-12 schools. Their findings are stark: Schools in formerly redlined zones still receive less per-pupil funding than those located elsewhere, they are still significantly racially segregated, and they still find themselves on the wrong end of pervasive achievement gaps.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter