Kids Left Schools Last Year Because of the Switch to Remote Classes; Early Numbers Suggest They May Not Be Coming Back Soon

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

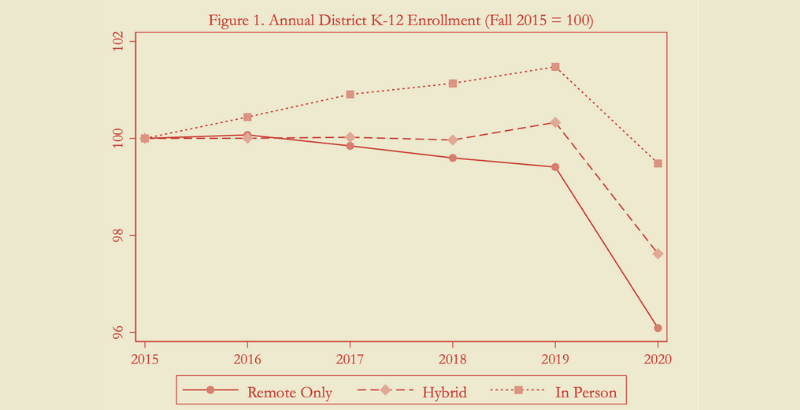

With the release of new data in recent months, a clearer picture is emerging of how K-12 enrollment has responded to the pandemic. Studying figures from hundreds of school districts, researchers at Stanford have found that roughly one-quarter of the decrease in students is directly attributable to the move to all-virtual instruction, and that the trend mostly affected the very youngest students. And early indicators from states and school districts suggest that total enrollment won’t bounce back to the pre-COVID status quo this year.

Thomas Dee, an economist and one of the Stanford co-authors, said that it wasn’t yet clear if or when the declines would be reversed, or how families might plan their re-entry into local schools. But a clear line connected remote schooling to fewer kids, he argued.

“Unsurprisingly, parents particularly didn’t want younger children — kindergarten or elementary-grade kids — sitting in front of a computer all day,” Dee said. “We’ve seen that in the enrollment declines, and what it implies is that some kids were missing out on those early developmental experiences, educational experiences we know can be really critical and have lifelong implications for them.”

According to the study, released in August as a working paper through the National Bureau of Economic Research, kindergarten enrollment fell by 3-4 percent in districts that opted for all-virtual instruction last fall. Elementary school enrollment fell by about 1 percent, while middle and high school enrollment was mostly unchanged.

To reach those conclusions, the research team painstakingly assembled data on student enrollment, as well as grade-level enrollment, from state departments of education, comparing 2020-21 figures with those of the preceding four school years. They also relied on data from Burbio.com, which tracks how school districts are offering instruction during the pandemic. The authors ultimately assembled a sample of 875 districts serving over one-third of all American K-12 students. While about half of those districts opened the 2020-21 school year in remote-only instruction, the other half was divided between those holding in-person classes and those using a hybrid model.

All told, they found that offering all-remote classes led to an enrollment drop of 1.1 percentage points, or roughly 300,000 students. Notably, the scale of disenrollment resulting from all-remote school was greater in demographically identifiable areas, such as rural districts and those serving more Hispanic students. The effects were almost twice as large in districts with lower concentrations of African American students, a phenomenon that could reflect attitudes previously expressed in public polling: Black parents of school-aged children were more than twice as likely as white parents to say they favored online classes, according to a survey conducted before the 2020-21 school year began.

The Stanford findings dovetail somewhat with those of other recent publications. A research brief released in September by scholars at the University of Michigan and Boston University also detected evidence of significant enrollment drops in Michigan public schools, with coinciding increases in private school enrollment and the rate of homeschooling. Another paper co-authored by Dee and University of Hawaii professor Mark Murphy showed a 4 percent decline among K-12 students in Massachusetts between the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years, with larger effects in smaller districts and those serving more white families. Finally, national data from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools points to a huge increase in charter enrollment last year.

Dee described the initial numbers coming out of states and districts as an imperfect tool, but one that currently offers the best guide to how families across the country have reacted to the unprecedented disruptions of COVID-19.

“I view the enrollment data as a sort of canary in a coal mine: a leading indicator that doesn’t capture the nuance we want in understanding what’s going on with kids, but that has the virtue of being available relatively quickly and comprehensively, representing the whole universe of public schools.”

‘Counts aren’t rebounding’

While education observers are still getting a sense of how many students left traditional public schools last fall, the first inklings about the current school year are already becoming available. And so far, they don’t foretell a mass return of students who sat out last year.

Figures released this week by the Los Angeles Unified School District — the second-largest in the U.S. after New York City — show about 27,000 fewer students showed up for classes this September than last September. That represents a 6 percent decline in total enrollment, even as schools in L.A. have long since reopened for in-person classes.

Disenrollment has also persisted in Hawaii which has already released student counts for this year. Total kindergarten enrollment on the islands — which operate as a single, statewide school district — saw one of the steepest declines in the country during the pandemic, falling from 13,074 in 2019 to 11,103 in 2020. But while some have predicted an early education “surge” this year as parents finally place their kids in kindergarten, it has so far been absent; kindergarten enrollment is up by about 350, but still remains about 12 percent below the pre-pandemic status quo.

“What we’re seeing is that the fall 2021 counts are not rebounding to what we saw [before the pandemic],” said Mark Murphy, Dee’s co-author on the Massachusetts paper. “I think it’s starting to suggest that what we saw in fall 2020 may occur more commonly in fall 2021 than we originally thought.”

Instead, Murphy noted, the number of first graders has grown — an indication that families who “red-shirted” their children last year may have opted to place them directly into first grade this September. Meanwhile, the two-year decline between 2019 and 2021 is still substantial in grades two, three, and four.

Murphy did reflect that changing perceptions of the COVID threat may still be influencing the decisions of families. The emergence of the Delta variant in late summer resulted in a spike in both cases and hospitalizations in Hawaii, which likely preyed on the minds of concerned parents.

“There may be some changes in the response to how families are thinking about enrolling their children given the changing dynamics, and the greater intensity of the Delta variant may impact individuals’ behavior.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter