Falling Birth Rates Spur Clash over Race and School Choice in Michigan

By Kevin Mahnken | June 24, 2021

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

The well-heeled suburban enclave of Grosse Pointe, just across the border from Detroit, is home to some of the best schools in Michigan, according to just about any measure you choose. Online raters like Niche and U.S. News & World Report have issued high grades to both the district as a whole and its high schools. The local average SAT score places comfortably above the national average. And just in the last five years, separate elementary schools were selected for the prestigious National Blue Ribbon Schools program in 2016 and 2017.

Given the criticism often directed at Michigan’s education performance, one might think that demand for a seat in Grosse Pointe would make school closures unthinkable.

And yet, at the end of the 2018-19 school year, members of the local board voted to shutter Trombly Elementary School, located in the district’s south side, and Poupard Elementary School, at the northern end. The decision triggered a passionate if unsuccessful campaign to save the schools and a strikingly antagonistic school board race last November. But local education leaders say it was spurred by factors outside their control — there simply aren’t enough kids.

“This is a birth rate issue,” said Gary Niehaus, Grosse Pointe’s outgoing superintendent. “It’s not that everyone’s moving to a private school because we’re not doing a good job; you’re dealing with a human being that’s not been born. What you have in our district is 750 high school seniors leaving the district each year to go to college or trade school, and you’re entering in somewhere between 450 and 500 kindergarteners.”

The phenomenon of fewer children being born, leading to gradually shrinking school enrollments, is not confined to Michigan. According to provisional data released last month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, total births in the United States fell 4 percent last year, reaching the lowest number since 1979. Between 2019 and 2020, fertility decreased for women across all racial and ethnic categories and in all age groups between 15 and 44. And while the disruptions of COVID-19 undoubtedly dissuaded some women from starting or expanding their families last year, the long-term decline has been in the works for well over a decade.

But in Michigan, the picture is further clouded by local education policy, which both grants families a huge degree of public school choice and mandates that funding follows students when they change schools. To cope with a smaller pool of total students, districts must attract as many pupils as possible to attend their traditional schools. Some succeed brilliantly, drawing families and funding from surrounding areas; those that can’t do the same see their head counts diminish.

And districts like Grosse Pointe are stuck in the middle: in clear need of more children to educate, but unwilling to accept the predominantly nonwhite and low-income pupils nearest to them.

David Arsen, a professor of educational administration at Michigan State University, argued that the era of collapsing enrollment need not precipitate a nationwide school funding crisis. If state K-12 education revenues remain the same, all else being equal, then lower fertility could lead to higher per-pupil expenditures. But when viewed from the perspective of individual districts, which build their budgets on total student numbers, a downturn in enrollment represents “a powerful loss in revenue, just as increasing enrollment is beneficial.”

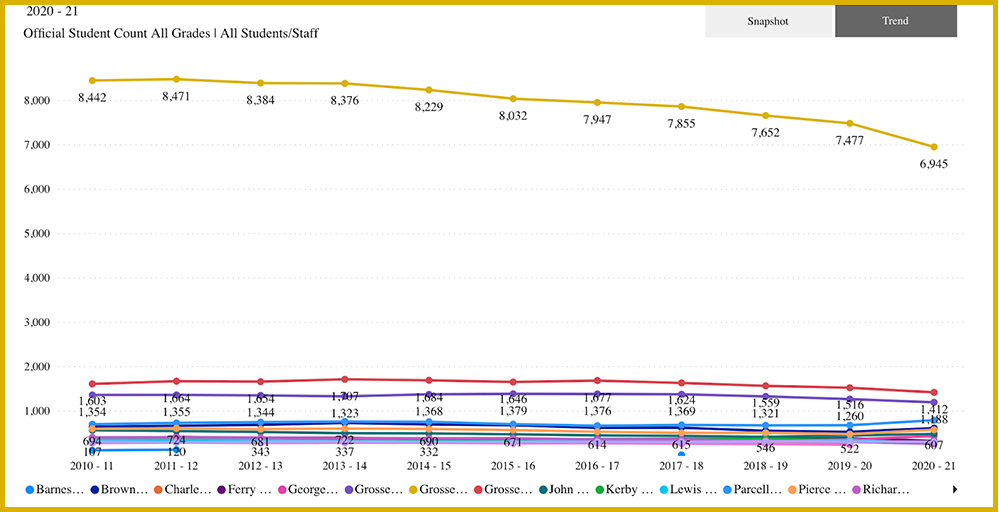

The example of the Grosse Pointe Public School System, which serves the five municipalities that collectively make up Grosse Pointe, is instructive: State data show that total K-12 enrollment has fallen by about 1,500 in less than a decade, capped by a huge reduction during the year of distance learning necessitated by COVID-19. Each student lost, or never enrolled, represents over $10,000 in education funding from the state that doesn’t reach the district.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about it, and [districts] have to do what they can to try to keep enrollments up,” Arsen said. “This is a trend that’s sweeping through the national education system, but I think we’re ahead of the curve in Michigan. There’s competition for students by any means necessary because the money’s going to come with the kids.”

The Picture in Michigan

According to the CDC’s data, Michigan recorded just under 104,000 babies last year. That made it one of 25 states in which total deaths exceeded births during that span, when the pandemic resulted in massive loss of life. But the extended fertility decline reaches back far past the emergence of COVID, and the 2020 birth count is roughly one-third lower than it was in 1990.

(Spencer Platt / Getty Images)

Much of the change is linked to a local economy that stumbled through a “one-state recession” over the first decade of the 21st century, during which per-capita personal income fell from 18th in the nation to 38th. Given the relative softness of local industry — led by a swiftly contracting automotive sector that historically acted like a regional magnet for labor — the state has tended to draw fewer young workers who might eventually start families. Consequently, Michigan routinely ranks among the states where native-born residents make up the largest share of the population.

Career data analyst Kurt Metzger has a unique perspective on the problem as both an observer and policy maker. A longtime student of population flows in Michigan, he helped establish the influential research group Data Driven Detroit, then left in 2013 after being elected mayor of Pleasant Ridge, a Motor City suburb of about 2,500. In an interview, he lamented that the state had failed to attract more transplants and was on the verge of losing a congressional seat.

“We lose a lot of young people, and we’re not very good at attracting young people,” Metzger said. “So our state continues to age, and we’re not adding a large number of people in their child-bearing years. And if you combine that with the economic outlook, people delaying marriage, having fewer children — it kind of compounds in Michigan.”

The effect on school attendance is undeniable. Between 2003 and 2018, statewide school enrollment plummeted by 16 percent. A report from local site MLive put the dropoff in even starker terms: Amazingly, in the period between 2009 and 2019, 78 different districts in Michigan — roughly 15 percent of the state’s 537 total districts — lost more than one-quarter of their students. Overall, three-quarters of all school districts had seen student losses of some magnitude.

COVID-19 has clearly hastened the process already underway. According to state data, there were about 40,000 fewer students across all of Michigan’s K-12 grades in the 2019-20 school year than in 2015-16. But in the fall of 2020 alone, schools took in over 50,000 fewer kids than the year before. A healthy percentage of the missing are incoming kindergartners whose parents will likely place them in public schools after an extra year of seasoning at home. But according to Ben DeGrow, director of education policy at Michigan’s right-leaning Mackinac Center, some may never find their way back into public school classrooms.

“I think that not all those students are lost from the public school system, but a significant number of them are gone permanently,” he said. “Which probably just slightly accelerates all these decisions about closures and consolidations. And the reckoning will come due in a few years.”

Metzger has seen the trend play out personally. Pleasant Ridge sends its own K-12 students to attend the neighboring Ferndale school district, which opted to sell several older school buildings to developers a few years ago. He argued that while the resulting merger had its limitations, it was a necessary acknowledgment of the under-filled classrooms that predominate in many of the state’s schools.

“We just have too damn many schools, too many school districts, too many administrators, and it makes no sense. I don’t see how the product we’re delivering can possibly improve, [given] the way we operate a K-12 system in this state.”

A ‘spiral of decline’

But shifts in demography alone do not explain the situation in Michigan. Along with a shrinking number of potential students, some districts are also losing out against competitors.

Two of the most important features of the local education policy landscape relate to school choice. One is the state’s expansive charter school sector, which enrolls roughly 150,000 students statewide. The other is the ambitious Schools of Choice program, an inter-district enrollment protocol that allows students to leave their own school system to fill openings in participating districts. Between the two, about one out of every four public K-12 students in Michigan attend a school outside their residential district.

That means that struggling school districts — often those enrolling high percentages of low-income students and students of color — see their head counts dwindle as families enroll their children in neighboring cities and towns. Major urban centers like Detroit and Flint, practically national bywords for underperforming schools and failed public sectors generally, have been among the biggest losers.

Another is Benton Harbor. An overwhelmingly African American community nestled on the shores of Lake Michigan, the city’s schools have long posted some of the worst academic results in the state. Rampant financial mismanagement, including embezzlement by a former superintendent, made matters even worse. With students rushing to the exits and money flowing out with them, the district found itself over $18 million in debt in 2019. At that point, newly elected Gov. Gretchen Whitmer called for locals to shutter its only high school or even dissolve the school system entirely. A furious advocacy campaign beat back the closure discussion, but education leaders are still working overtime to fill local classrooms.

Superintendent Andraé Townsel, appointed to the job just last year, said he was doing everything he could to “earn back” the approximately 3,000 students who live within the district but choose not to attend traditional schools. But Benton Harbor was locked in an “extremely competitive” hunt for an ever-smaller number of young people, he said, and the financial impact of the displacement was damaging.

“Less students, less money,” he said. “Across the country, every student is worth a certain amount that you get to educate them, and if you don’t have them, you don’t get it.”

Arsen said that the inter-district exodus of students flows “overwhelmingly [to districts] up higher on the socioeconomic totem pole.” Many migrate into new schools that are whiter, higher-income, and higher-performing academically than their home districts. The winners are able to compensate for the children who aren’t being born, but the losers are caught in a vicious cycle: Poor educational results leading to departing students, which in turn lead to less funding from Lansing.

“This feature of inter-district choice policy has helped stabilize enrollment and funding in some of Michigan’s communities,” said Arsen. “Of course, it’s a strategy that [appeals] more to advantaged districts, and it only aggravates the pain of the less advantaged districts. It sends them into a spiral of decline.”

The vast majority of Michigan districts participate in Schools of Choice. A notable exception is Grosse Pointe. Even as in-district birth rates have sagged and high property values make it difficult for young families to afford to move there, the board of education has refused to open its schools to children from nearby Detroit, where the student population during the 2020-21 academic year was over 97 percent nonwhite. When several proposals for right-sizing the district were first presented in a January 2019 board meeting, including closures and grade reconfigurations, it was repeatedly made explicit that a move toward inter-district enrollment was a non-starter. In this, officials were responding to the views of their electorate; according to one poll from last year, 70 percent of Grosse Pointe residents support the district’s position of not taking part in Schools of Choice.

Amanda Matheson, the district’s deputy superintendent for business services, said that the towering reputation of Grosse Pointe schools meant that it would have no difficulty enrolling commuter students if it chose to.

“If we wanted to keep those buildings open, we could have easily opened to Schools of Choice, and I can guarantee, based on the surrounding districts, that we would have been able to fill every single open seat we have,” she said. “But absent opening for Schools of Choice, our natural population for the kids who live within our boundaries is declining: lower birth rates, compared with the graduating senior class. And it’s true across the state.”

A relatively new arrival to the area, Matheson has previously worked in other Michigan districts that gladly welcomed inter-district transfers as a means of propping up enrollment. Initially, she said, she was surprised that local education leaders would leave such a potent tool on the shelf when the alternative meant closing their own elementary schools. But she added that the reluctance to open the district barriers reflected something of “the culture we have here.”

“You can’t pick and choose who you let in and how long you let them in for,” she said. “Once you admit them, they’re your students.”

“It would get me fired in a heartbeat” —Superintendent Gary Niehaus, asked whether he’d advocate opening Grosse Pointe schools to students from Detroit.

Pleasant Ridge’s Metzger said that education leaders in southeast Michigan — the home to much of the state’s population and industry, with the suburban layer of metropolitan Detroit growing more racially diverse even as the city ranks as the most segregated in the country — are facing the conundrum of protecting their bottom lines without alienating families.

“District parents start saying, ‘The school quality is going down, there’s fights in the school,’” he said. “Everybody comes up with their own code words, and the district has to fight that too..”

Superintendent Niehaus, who announced in September that he would retire at the end of the 2020-21 school year, also characterized Schools of Choice as a kind of third rail in local discussions, adding that the board would not adopt the policy even if he declared that “it was the greatest thing that could happen to us.” Asked whether he would make such a recommendation, Niehaus was equally adamant: “Not whatsoever, no. It would get me fired in a heartbeat.”

‘People would rather welcome the fish’

The sharp division between Grosse Pointe and Detroit did not arise overnight. Fierce debates over school assignment date back at least to the 1974 Supreme Court decision in Milliken v. Bradley, which held that 53 mostly white districts outside of Detroit — including Grosse Pointe — did not have to participate in inter-district busing unless their borders were clearly drawn with discriminatory intent.

The line between the communities is still among the most economically and racially segregated in the United States, according to a report by the nonprofit group EdBuild. In recent years, Grosse Pointe has erected a variety of physical barriers on its border with Detroit. It has also vigilantly enforced habitation rules for enrollment in public schools, with families required to produce multiple documents proving that they live within district boundaries. For years, an anonymous tip line allowed suspicious residents to report students they believed to be receiving a Grosse Pointe education from outside the district. Some years, over 100 tips were received.

Renee Jakubowski, a mother of three children who recently attended the now-defunct Trombly Elementary School, said that an air of distrust prevailed in some parts of the district, largely because of a “vocal minority” of people who suspect that low-income and non-white students couldn’t possibly live in Grosse Pointe.

“Our residency requirements — the hoops you have to jump through are tedious, to say the least,” she said. “If your kid goes from elementary to middle school, you’ve got to reaffirm [your address]. I just find it a shame. Kids are kids, they all need education.”

The anguished racial politics made decisions over school consolidation even more challenging. Some noted that Poupard Elementary, which served about 300 mostly African American and low-income students, was targeted for closure in spite of being the district’s only Title I school. Families connected to Trombly showed their discontent by marching en masse along the busy road that their children would have to cross in order to reach the next-closest elementary school.

A representative of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission called for the district’s leaders to be more mindful of Grosse Pointe’s history of racist and restrictive housing policies. In an interview with The 74, Cynthia Douglas, president of the Grosse Pointe branch of the NAACP, agreed that the public outreach process was “flawed.”

“On the financial side of it, we understood why they had to close the schools, why this had to be done,” she said. “But it disenfranchised a group of people, and the outcome of that and the atmosphere around the whole situation was not very favorable.”

Things got uglier when the decision was finalized, with an unsuccessful recall campaign launched against three school board members. Within six months, the president of the board stepped down, complaining of the harsh treatment he and his family received in the wake of the closure decision. Political tactics and tone became so hostile in last year’s board elections that the body even voted to censure one of its own members for working with a 501(c)(4) organization to malign district employees during the campaign. Deputy Superintendent Matheson, who had not joined the district when the closures were decided, said that the public backlash throughout 2020 was “very reflective of discontent with the decisions made” the years before.

“You could change curriculum, buy new textbooks, and you don’t have anybody show up [to meetings] when those items are on the agenda,” Matheson said. “But when you’re talking about school closures, it certainly brings out a lot of people, and it’s often very emotionally based because it is their school. It triggers emotions that people probably didn’t even know that they had, and concerns about how their kids will integrate with kids at other schools.”

The elections ultimately elected several members who expressly wanted to reopen Trombly and Poupard, but not enough to make a majority on the seven-member board. The two schools remained closed even as the pandemic led Grosse Pointe to abruptly embrace social distancing in schools. Jakubowski, who helped lead protests against the shuttering of Trombly, said she was resigned to the finality of its closure.

She held out even less hope that Grosse Pointe would open its schools to children from outside the community.

“I don’t see it happening in my lifetime. We’d have to have an enormous turnover in the community before that would be considered. We’re bordered on one side by Detroit, and the other side is the lake; people would rather welcome the fish.”

Lead art by Meghan Gallagher (Photos from Getty Images and Renee Jakubowski)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter