Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Across the country each year, thousands of teaching candidates get ready to begin their classroom careers. They finish up their graduate coursework, start scanning excitedly for job openings — and then fail their states’ teacher licensure exams. Dejected and daunted by the prospect of retaking the test, many never become teachers.

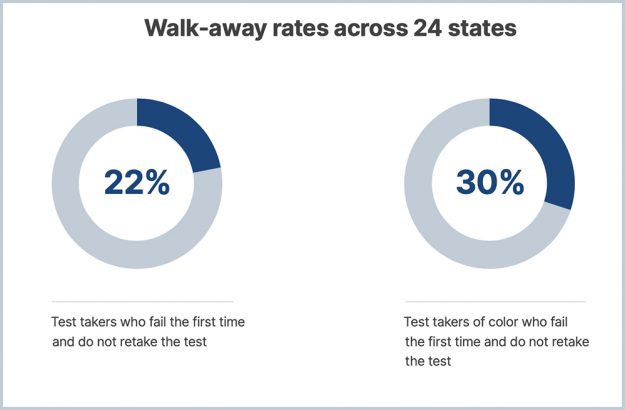

It’s a distressing pattern that has been documented for years and increasingly draws the focus of policymakers attempting to diversify the profession. As more experts point to the improved academic performance of students who are assigned to even one instructor of the same racial or ethnic background, some advocates have called for states to modify, or even scrap, their licensure tests, which are more likely to be a stumbling block to African American and Hispanic candidates.

A report released today by the National Council on Teacher Quality, a reform-oriented think tank based in Washington, D.C., puts the issue in perspective. Data gathered from 38 states and the District of Columbia show that a huge portion of prospective elementary school teachers don’t pass their licensing exam on the first try. Of those that fail, non-white teachers are much less likely to re-take the test than their white classmates. And within states, students at different institutions faced radically different odds of ultimately securing a teaching credential. The conclusions will lead many to wonder whether novice educators are receiving enough training before being hired, and what can be done to assist those who weren’t adequately prepared.

NCTQ president Kate Walsh, a longtime and often critical observer of teacher prep programs, said in an interview that while the results were themselves “terrible,” a more pressing concern was the sheer difficulty of obtaining the evidence. State authorities should be active in publicizing that information, she argued, but many don’t even bother to collect it, and even federal efforts to investigate these questions have been “mired in confusion.”

“What’s interesting to me is that states didn’t have this data,” Walsh said. “We thought they did, but almost all states said that this was the first time they’d ever seen this data.”

The national findings, encompassing program-level exam results between 2015 and 2018, demonstrate clearly that large numbers of graduate students struggle to reach the finish line and become licensed teachers. Across all states that provided data, the average “best-attempt” rate for prep programs — the rate at which test-takers ever pass the test, whether or not they fail on their first try — is 83 percent, meaning that roughly one in six don’t realize their ambitions. And certain programs do much better than others: The average gap between the highest-performing and lowest-performing institutions in each state was 44 percentage points.

What’s more, 29 percent of all prep programs reported that less than half of their teaching students passed the licensing exam on their first try. Six states (Connecticut, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Virginia) were home to at least one program in which no teaching candidate did so.

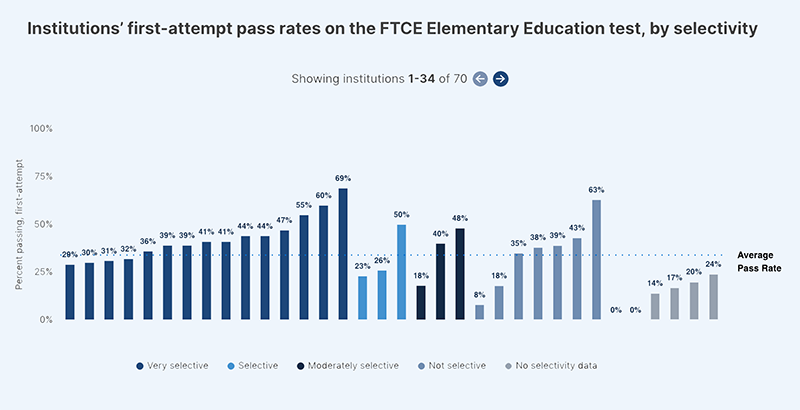

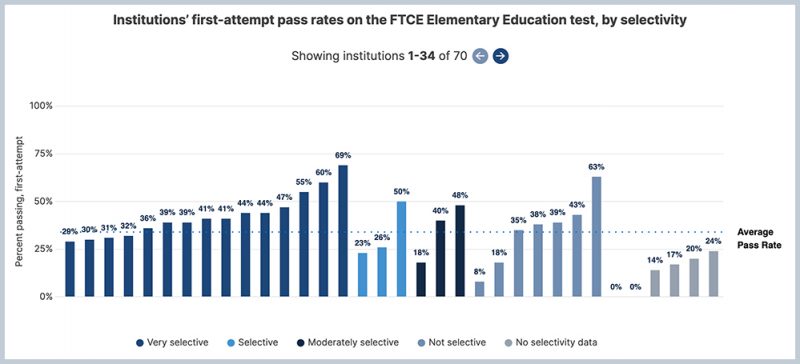

Florida, which employs the fourth-most teachers of any state, offers a revealing example. In the three years studied, two different teacher prep institutions saw no teaching candidates pass the Florida Teacher Certification Examinations their first time, though both are tiny programs serving roughly a dozen students between them. Many others — including Florida International University, Florida Gulf Coast University, University of North Florida, and University of Central Florida — reported first-time pass rates of 41 percent or less. All of those schools, which collectively produced over 2,300 test-takers, were rated by NCTQ as among the most selective in the state.

At the same time, a huge number of Florida’s prospective teachers who failed their licensure tests the first time go on to pass in later attempts, likely with the support and encouragement of their prep programs. And a substantial number of programs enrolling large numbers of low-income students (measured via their eligibility to receive Pell grants) report higher first-time pass rates than the average across the state.

Dan Goldhaber, a professor at the University of Washington who directs the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER), called the data “compelling,” adding that researchers might fruitfully study which institutions are able to work best with teaching candidates who initially stumble with the exam.

The findings “begin to open up the teacher preparation black box a little bit and point to where we should be looking for different supports, curricula, interventions that seem to be able to help teacher candidates while they are in teacher preparation,” Goldhaber said.

Dodging the ‘heat’ of publication

In order to reach their findings, NCTQ first had to receive the data from states. A 2019 study, using national results for the commonly used Praxis exam that were provided by the testing vendor ETS, offered somewhat similar findings, but did not delve into differences by state or institution.

Acquiring results at that more granular level was much harder, Walsh said, because some local authorities “didn’t want the heat of being the ones to publish this data.” In all, seven states did not provide timely data on licensure exam performance, and eight provided only partial data. Of the states that did share their data with NCTQ, some had to be subjected to public records requests.

Meagan Comb, director of the Wheelock Educational Policy Center at Boston University and a one-time NCTQ fellow, said she wasn’t particularly surprised at the challenges posed by a third-party examination of test results. In a two-year stint as the director of educator effectiveness at Massachusetts’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, Comb oversaw the state’s policy on both teacher preparation and licensure. She recalled that many in the state — considered a national leader in the collection and dissemination of education data — had ached for more information because “it was really hard to know how our pass rates compared with other states.” This often included program heads themselves, who didn’t always have a clear picture of which student groups were struggling or what aspects of the test gave them trouble.

“This report shows that you have to invest in data infrastructure,” Comb Said. There are a lot of states that can’t even link their teacher workforce with their teacher prep candidates, or there’s a state statute prohibiting them from looking at the efficacy of their teacher candidates. I think there’s a lot of opportunity in states across the country to think a lot about the data infrastructure they provide to teacher preparation programs for continuous improvement.”

Goldhaber noted that bottlenecks on data can arise in different areas. While some state education departments are “more inquisitive than others,” he acknowledged, schools of education would often prefer that low pass rates float under the radar.

“I think that, sometimes, the politics are really hard,” he said. “You have important political constituencies — deans, and everything they bring — who sometimes don’t want these data to be out there.”

Lack of transparency can be damaging not only to state authorities, and prep programs themselves, but also to prospective graduate students, some of whom will enroll unwittingly in a teacher prep program where they stand a significant chance of not gaining a license. The risk of failure is especially great for teaching candidates of color, who are significantly less likely than white candidates to retake the exam if they fail. The stress and expenses associated with the test, often amounting to hundreds of dollars in fees or preparation materials, can act as a roadblock to attracting more diverse teachers.

Walsh said that on grounds of consumer protection alone, that had to change.

“The whole point is, you’re supposed to be preparing candidates for licensure. And nobody points out to the kids going into these programs, ‘Your chances of getting a license at this institution are nil.’ So they take their money, take their time, and that’s it.”

Disclosure: The Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provide financial support for both the National Council on Teacher Quality and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter