Critical Race Theory and the New ‘Massive Resistance’

By Mark Keierleber | August 18, 2021

Why some are comparing the national backlash against anti-racist teaching to Virginia’s strident campaign to resist school desegregation after Brown v. Board of Education

Arnold Ambers was still a teenager when he woke up at 4 a.m., jumped behind the wheel of a rickety bus and shuttled dozens of children to a nearby segregated elementary school. Much of the fleet lacked heat and, on the coldest mornings of those Virginia winters, he’d pull over on the side of the road to brush ice off the windshield with a worn towel.

After finishing the route, Ambers arrived late to his all-Black high school, named in honor of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, which remained racially segregated despite the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education years earlier. As Ambers bused children to racially isolated schools even after the court found such segregation unconstitutional in 1954, officials fought tooth and nail to keep it that way. As one of the nation’s last holdouts, Loudoun County schools remained racially isolated until desegregation began in 1968. Such discrimination was so pervasive that it became baked into Ambers’ perception of normality.

“That was the sign of the times,” the 79-year-old Ambers said, recalling how his family was barred from many public spaces outside the balcony of a Leesburg theater. But by the time he enrolled at Shaw University, a historically Black institution in North Carolina, he’d had enough and joined civil rights protests, marching and singing songs like “We Shall Overcome.” But “white folks didn’t take kindly to Black people demonstrating,” and he’ll never forget the occasion an irate man spit on him. “It’s one of the most degrading things that you could ever do.”

These days, Ambers is on edge. The racial strife that’s engulfed the county in the last several years, he said, brings back memories of Jim Crow.

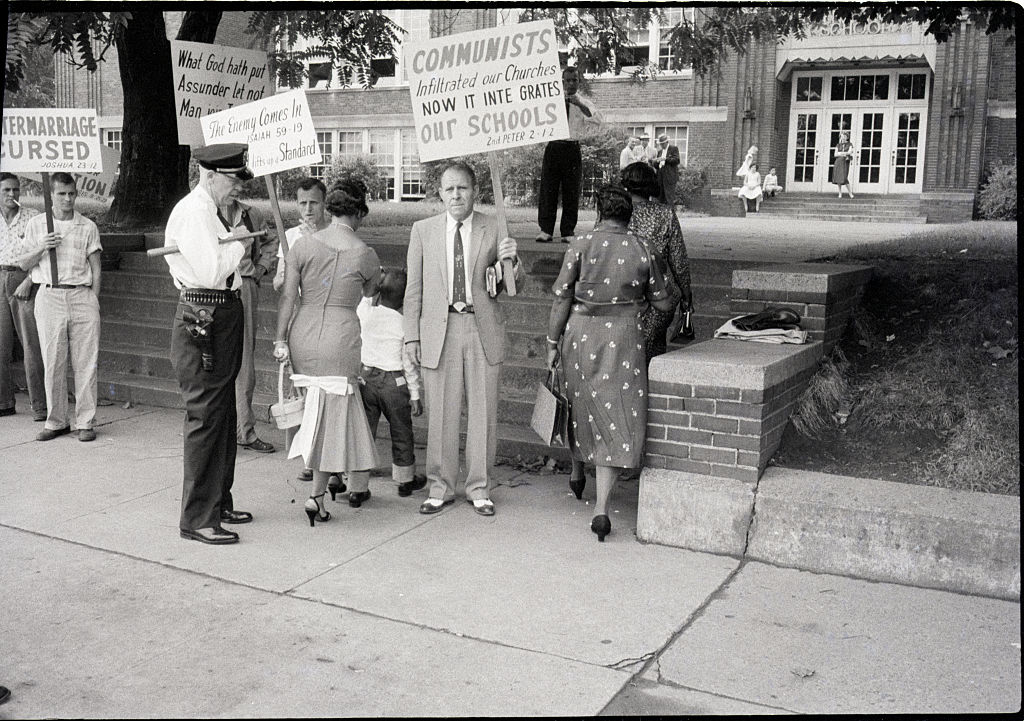

This year, Loudoun County has become ground zero for a national uproar over schools’ use of critical race theory, a legal concept that’s seemingly been bastardized to encompass any instruction about systemic racism and Black Americans’ enduring struggle for racial equity. That strife came to a head at a school board meeting in June, when one man was arrested and another injured after the gathering descended into chaos as parents protested critical race theory with signs that read “education not indoctrination.”

“It’s painful to realize that we’ve come a long way, but in the last five years we’ve really gone backwards quite a bit,” Ambers said. “And I guess the painful reality is that racism has always been there.”

For some observers, the backlash is part of the complex, centuries-long history of racism and oppression that some educators have sought to confront, particularly after George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020. Specifically, they’ve likened the blustering rhetoric of critical race theory’s staunchest critics — and legislative efforts across the state to prohibit teachers from discussing systemic racism — to “massive resistance,” an effort by white segregationists in Virginia to thwart school desegregation for years after the Brown decision.

Among them is Juli Briskman, a Democratic member of the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, who referred to the current upheaval as “the massive resistance of our generation.” Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which litigated Brown, quipped that segregationists and the current dissidents mobilized around a singular force: “The unifying power of whiteness.”

Locked out

While white segregationists employed legal, and sometimes violent, tactics to evade school desegregation, critics said that similar strategies are now being leveraged to block educators from teaching about that very historic reality.

As the rancor reaches a fever pitch nationally, some parents have pulled their kids from public schools and others have touted private school choice as an option to shield children from “curricula permeated with ideas we find toxic.” In July, a teacher in Tennessee was fired for teaching students about racism and white privilege.

Meanwhile on Fox News, which has warned against the dangers of critical race theory thousands of times this year, pundit Tucker Carlson suggested — next to a graphic of the Democratic Party logo and the words “ANTI-WHITE MANIA” — that classrooms be equipped with cameras to ensure teachers aren’t filling impressionable young minds with “civilization-ending poison.”

In nearly half of states, Republican lawmakers have introduced legislation this year that seeks to limit how educators discuss racism and other “divisive” issues, and in 10 states such bans have become law. Under a new Tennessee law, for example, public schools could lose funding. In Arizona, teachers could have their licenses revoked.

Jin Hee Lee, the senior deputy director at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, finds the current efforts similar to resistance to desegregation in that both operate on nostalgia that fails to recognize how educational inequities upheld by the status quo marginalize Black children and could be detrimental by further destabilizing public education.

“The idea that any efforts to engage and remedy that problem is somehow in itself harmful to other children is beyond ironic, it’s really quite tragic,” she said. “An accurate accounting of history and the requirement that all children should be treated equally, and to be included, is beneficial for everyone.”

Jamel Donnor, a critical race theory expert and associate professor of education at Virginia’s College of William & Mary, also sees similar parallels between the backlash to critical race theory, which he called a boogeyman, and Southern resistance to school desegregation. Even to this day, K-12 schools are starkly divided by race and integration efforts remain divisive even in northern enclaves like New York City. In both instances, he said the uproar centers on resistance to inclusion.

“First it was the inclusion of black bodies,” he said. “Now, it’s the inclusion of ideas [and] materials that purport to provide a more holistic picture, a more holistic understanding of the experiences of people of color in the United States.”

Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian at the University of Pennsylvania, acknowledged similarities between massive resistance and the current backlash with outright racism as a key motivator, but several differences muddle the analogy. Massive resistance after Brown was a battle over the Constitution and its interpretation, he said, while the current feud is largely about American identity.

Many white Americans in particular are “deeply invested in a narrative of America” that’s being challenged, and while he doesn’t endorse their perspective, he said they come “from a correct perception that these stories represent a radical difference from the stories they were invested in.” Meanwhile, he said that in some cases the most ardent proponents of anti-racist teaching have imposed their opinions about history on students. Laws that bar teachers from discussing “divisive” topics have the same effect.

“All truths are subject to interpretation and there is no singular, unvarnished truth,” he said. “Never has been, never will be.”

‘The most serious blow’

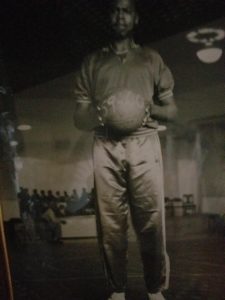

The very existence of the segregated Douglass School, where Ambers graduated in 1960, was a feat in itself.

To the backdrop of white resistance, members of Loudoun County’s Black community, including Ambers’s father, held chicken dinners and other fundraisers to buy a plot of land on the outskirts of Leesburg for the county’s first high school for Black children. The school was built in 1941, after organizers sold the land to the county for $1, and the county’s Black community raised money to fill the building with desks and books.

Ambers and other students at Douglass weren’t offered the same opportunities as the county’s white children and almost immediately after the Brown decision was released, white officials in Virginia and across the South vowed to keep it that way. A prominent force was Virginia Sen. Harry Byrd, who blasted Brown as “the most serious blow that has yet been struck” against states’ rights — an argument that echoed the “Lost Cause,” in which Confederate officials sought to inaccurately portray the Civil War as a feud over local control rather than an effort to uphold slavery.

Virginia officials created the Gray Commission, which recommended officials amend the state compulsory attendance law so white children didn’t have to attend integrated schools and the creation of taxpayer-funded “tuition grants” so parents could send their children to private institutions known today as “segregation academies.” Two years later, Byrd launched a campaign that became known as “massive resistance” that included a collection of laws aimed at preventing integration, including a policy to pull funding from schools that allowed Black and white children to sit in the same classroom. Through newly created tuition grants, money from closed public schools was funneled to private schools that weren’t bound by Brown’s mandates. After the school-closure law was found unconstitutional in 1959, state lawmakers repealed school attendance rules and created a “local option” that gave cities and counties authority to close schools.

In Loudoun County, educational inequities upheld by racial segregation were felt in teacher salaries, transportation and facilities. At the Bull Run school, Black children brought lumps of coal each morning to provide the building with heat and others hauled in water from a nearby stream.

Shortly after Brown, county officials voted to let students use public education funds for private schools, in effect allowing white families to cover tuition costs while sidestepping integration. In a resolution, officials voted to stop public funding “if the federal government forced integration,” a reality that came to fruition only after years of legal battles. But the animosity lingered long after and white resistance extended beyond public education. In the mid-1960s, Black youth wanted to swim in Leesburg’s public pool but the volunteer fire department filled it with rocks and cement rather than see that happen. The town didn’t get another public pool until 1990.

Perhaps the most significant effort to resist desegregation unfolded in Prince Edward County, a rural Virginia enclave with deep ties to the Brown decision. It was here, in 1951, where Black high school students from Farmville went on strike over poor school conditions and sued for equity. Their legal struggle was ultimately one of five cases consolidated into the Supreme Court’s Brown decision. Years later, however, segregationists retained the upper hand. Under pressure from two court desegregation orders in May 1959, officials chose to close the county’s entire public school system for five years rather than comply. White children were allowed to enroll in the private Prince Edward Academy, which became a model “segregation academy” for communities across the South, and many Black children, who were excluded from enrollment and unable to use tuition grants elsewhere, were effectively locked out of a formal education altogether.

Such efforts expanded beyond Virginia. By 1969, more than 200 private segregation academies were formed across the South and in seven states — Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana — families were allowed to use tuition grants, often called private school vouchers today, to avoid desegregated schools.

Rather than focusing on race, white residents in Loudoun County often spoke fondly of their Black neighbors and much of their rhetoric justifying the school closures centered on school privatization, local control and taxpayers’ rights. The Farmville Herald’s publisher at the time, a staunch segregationist, asserted in an editorial that if “Virginia, the mother of constitutional government” allowed school integration, it would have “permitted the rape of ideals and principles for which great men have given their minds and blood, suffering almost unbearable hardships.”

Christopher Bonastia, a Lehman College professor and author of Southern Stalemate: Five Years without Public Education in Prince Edward County, Virginia, described the massive resistance strategy through a simple quote: “If we can legislate, we can segregate.” Now, he said, some critical race theory critics have adopted a similar gameplan. “It seems to me that the theory is ‘if we can legislate, we can obfuscate,’ meaning that if we don’t allow this teaching of how racism is sort of baked into U.S. law and policy and practices, then we can maintain this racial innocence.”

He also sees similarities between the two camps’ overall rhetoric.

“This claim to colorblindness, which happened in Prince Edward, that is the kind of claim of the anti-CRT folks” who question why children should learn to be race-conscious instead of viewing everybody as equals. Lee of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund made a similar connection, noting that claims of colorblindness have been used to entrench existing racial disparities for generations.

“It ignores inequalities that exist and it ignores important conversations to try to remedy those racial inequalities,” she said. Claiming colorblindness doesn’t make inequality “just magically disappear. In fact, it’s very important for us to identify and examine inequalities that do exist.”

‘Fugitive pedagogy’ and the art of Black teaching

As Black students in Prince Edward County and elsewhere fought for educational equity, their struggle was about far more than access to white schools. The transformative vision of school integration also included “desegregating curriculum,” in which African-American experiences and voices were included in classroom instruction, said Jarvis Givens, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

In his Book Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, Givens traces the life of the “father of Black history,” and highlights how anti-racist teaching practices have long been a staple of Black educators’ approach to instruction — and doing so has always faced resistance.

To define “fugitive pedagogy,” Givens turns to the actions of Tessie McGee, a Black history teacher from Louisiana who, in the 1930s, kept a copy of Woodson’s “book on the Negro” on her lap, reading passages to students in defiance of state and district rules. Through her actions, Givens wrote, McGee “explicitly critiqued and negated white supremacy and anti-Black protocols of domination, but they often did so in discreet or partially concealed fashion,” as part of a larger vision to dismantle Jim Crow segregation while celebrating African Americans’ contributions to society. She and others did this at grave risk of getting caught.

For many Black educators, that was a real threat as they faced relentless suspicion and surveillance. Such surveillance, similar to Tucker Carlson’s call for cameras in classrooms, “has been endemic to the experiences of Black teachers historically.” Now, contemporary calls to police classroom instruction is worrisome, he said.

“Now we’re seeing it out in the open because a lot of folks are being given permission to kind of surveil what teachers are teaching,” he said, “and whether or not it adds up to their vision of what it means to be patriotic and American, and whether or not it’s consistent with the stories that we’ve been told that we need to tell about the past, of America’s history, for so long.”

Despite Black educators’ long history offering anti-racist instruction and being subjected to surveillance to prevent it, Givens said the issue has taken on a new form in the last year. Parents are so up in arms this year, he argued, because the instruction is being offered to white kids who are being asked to confront issues of racial inequality.

“I think the falling out has to do with the fact that there’s a lot of white people who don’t want their children learning these sorts of narratives because of what it implicates about their own identities in certain ways and the ways it names whiteness in explicit ways that causes discomfort for people,” he said. “That’s what’s really what’s at hand here: ‘What happens when we decide to include Black history in ways that go beyond the terms of what’s comfortable for white Americans?’”

Zimmerman, the University of Pennsylvania historian, said the current moment creates an opportunity for educators to present American history from multiple perspectives and allow students to grapple with the lessons rather than prescribing their own views. Yet partisans on both sides, he worried, are disinterested in an honest debate.

“I want more nuance,” he said, “but, to be as direct as possible, who the [heck] am I? How many people actually do want that and how do we make the case for it?”

‘A long-overdue apology’

For 45 years, Virginia’s efforts to defy Brown were placed on a pedestal outside the state capitol in Richmond. That era came to an end in July, when a 10-foot bronze statue of segregationist Sen. Byrd, the massive resistance architect, was removed from its perch and hauled off to storage.

Yet much of his legacy carries on unabated as schools across the country remain starkly segregated by race and some communities continue to leverage tactics, such as school district secessions, to resist integration.

Some of the very groups leading the charge against “critical race theory” are also engaged in efforts to block ongoing desegregation efforts today. In New York City, where public schools are among the most racially segregated, students filed a lawsuit this year arguing that the city’s use of selective admissions screens at its sought-after high schools, long seen by some as a hurdle keeping Black and Hispanic children from the lauded campuses, violate the state constitution. The lawsuit calls on the city to scrap its competitive admissions practices.

A new group called Parents Defending Education, which offers an “IndoctriNation Map” to fight “indoctrination in the classroom” by exposing educators “promoting harmful agendas,” sought to intervene in the New York City case. The student group’s efforts to strike down race-neutral admissions screens, the group wrote in a court filing, “is intentional racial discrimination, plain and simple.”

“Plaintiffs believe the best way to achieve equity is to focus on race and to break the parts of the city’s school system that are working,” the group, which didn’t respond to requests for comment, noted in court papers. Parents Defending Education “believes the best way to achieve equality is to treat children equally, regardless of skin color, and to fix the parts of the city’s schools that are broken.”

Despite the persistence of racial segregation in schools, some school leaders have sought in recent years to grapple with the past and how it still affects the education system today. After Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, for example, the head of a private school in Montgomery, Alabama, wrote an open letter about the role his school played in resisting desegregation. The Montgomery Academy opened in 1959 as an all-white school and “was seen by many as one of the early catalysts for the ‘white flight’ from Montgomery’s public schools.”

“We must be willing to confront the uncomfortable fact that The Montgomery Academy, like many other independent schools founded in the South during the late 1950s, was not immune to the divisive forces of racism that shaped this city and community over the course of its history,” John McWilliams, who didn’t respond to requests for comment, wrote in the letter. In his view, he wrote, Black Lives Matter protests that engulfed the country had clear ties to a centuries-long struggle. “I believe that we are witnessing the cumulative impact of over 400 years of white supremacy, racial division and discrimination play out in our streets and cities across the country.”

Ambers, who ironically finished his professional career as a school bus driver in Virginia’s Fairfax County, retiring in 2015, has been forced to face how racism in Leesburg schools persisted long after he left. Just recently, his three children, now adults, detailed to him for the first time how they experienced racial discrimination in the system long after the district was formally desegregated.

“They were called the N word and during Black history they were asked to explain things like they were considered slaves,” he said. “They were treated like ‘Well, you’re supposed to know about this so tell us about it.’”

Several years ago, the school district began to address issues of racial equity after high-profile reports found inequities negatively affected the academic progress among students of color, prompting school leaders to create a “Plan to Combat Systemic Racism,” including teacher trainings that focused on helping educators foster “racial consciousness.”

Then, in September 2020, county officials issued “a long-overdue apology to the Black community” for joining the campaign of massive resistance decades ago. While noting that much work must be done “to fully correct or eradicate matters of racial inequality” in the county, the officials wrote that county educators “must continually assess the status of racial equity in the school system and correct its past transgressions as it pertains to race.”

Even in the face of backlash and intimidation, Briskman, the county Board of Supervisors member who gained notoriety in 2017 when she gave former President Donald Trump’s motorcade the middle finger, vowed to carry on.

“The work is not going to stop,” she said, “and we’re not going to be threatened.”

Lead Image: In this photograph from 1961, teacher Althea Jones offers instruction to Black children in a one-room shack in Prince Edward County, Virginia. Beginning in 1959, the county lacked public school facilities for an estimated 1,700 Black children while some 1,400 white students attended private schools financed by state, county and private contributions made in lieu of tax payments. (Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter