J.A. Stokes — The Student Strike That Launched One of the Most Influential Civil Rights Movements in Virginia. ‘We Jump-Started Our Own Manhattan Project’

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

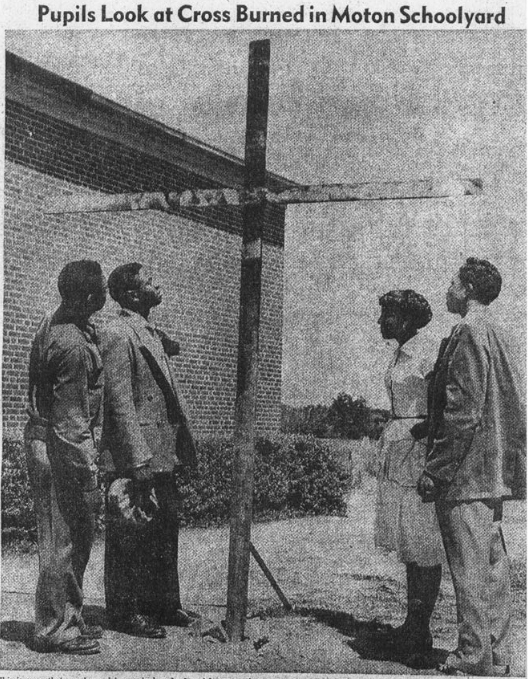

The smoldering cross dwarfed us. As the four of us — Admore Joiner, Thelma Allen, Rome Allen and I — craned our necks and fixed our eyes on the menacing reminder of racist terror, it sent chills through our entire beings. No, this was not an imagined threat; this was real.

The burning rags wrapped around the top portion of this heavy wooden structure had begun to burn out and fall to the ground. Its remnants were now curling around the base, withering like snakes, and slowly dying out. The pungent odor of chemicals and residue that had been used for this ungodly, eerie act filled the air with an intense putrid odor that penetrated the entire atmosphere surrounding the school.

The inner portions of my nostrils burned as I stood there. In that moment, the stench seemed to encompass the whole universe. The deadness settling over the area created a knot that gripped the pit of my stomach, making me want to regurgitate. This horrendous symbol was intended to intimidate us and to get even with the colored people who had filed a lawsuit against the Prince Edward County School Board and the man we called “oligarch”: Superintendent of Schools McIlwaine.

We had to wait for things to cool down before we could take a photo of this sight. Yes, this atrocious act was an attempt to instill fear into our hearts and minds so that we would remove our names from the petition declaring our opposition to unequal schools. Causing fear had been a traditional tactic used by the power structure to control the mindsets, concepts, ideals, ideas, progress and upward mobility of the downtrodden, the needy, the weak, the humble and the persons of color in Prince Edward County.

Those in authority wanted to control all facets of our lives. Once the powerful had weakened their victims, they would then gain full control. As a result, the oligarchy felt that they had lost control when colored folks in this bucolic area of Virginia rose up and challenged the establishment. They felt angry, even helpless, because a bunch of colored children had led the charge.

The Farmville Herald newspaper editor and other writers had a field day with our rebellion. Most of them could not fathom how a bunch of colored high school students were successful in pulling the wool over the eyes of the establishment in such a manner.

After calling us communists, they decided to ask questions: “How did the parents of these children permit them to do such an evil thing?” “Who gave these colored children permission to do this to us whites, people who have been so kind to the colored people in this community?” “How come the parents of these disobedient children did not whip them for being disrespectful to white folk?” “Who taught these children to act this way and think this way? There must be some outsiders who are teaching them how to think!!” “Our races will be ruined if we permit the white students and the colored children to attend school together!!” And, of course, the most irrational fear of all: “Our poor little white girls will be raped!!”

Boldly, we put our names on this petition for equality and justice for all. We knew that we would have targets on our backs for the remainder of our lives. Standing beneath this monument of evil reinforced my resolve to change this practice that had existed well before Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). With every fiber of my being, I vowed to change the status quo. It was then I decided to become an active member of the civil rights movement.

WATCH: J.A. Stokes reflects on Brown v. Board, 65 years later

Barbara Rose Johns initiated this movement when she approached us for advice. By “us,” I mean my sister, Carrie D.V. Stokes, and me. Carrie and I were two of the senior leaders at Robert Russa Moton High School. Carrie, my twin sister, had been elected president of the student body and held key roles in multiple clubs and organizations. I was president of the senior class, state president of the New Farmers of America for the state of Virginia, managing editor of the Motonian, the school newspaper, captain of the track team and captain of the debating team.

Barbara knew that we had leadership skills. We knew the lay of the land. As she told us: “I need you all because I know that I can trust you and because you know the students here.” Barbara had seen us operate; she realized that we knew how to bridge the gap that existed in schisms within the colored community.

Our first meeting took place on the hard cinderblock bleachers that served as part of our athletic field. The four of us — Barbara Johns, Carrie Stokes, Irene Taylor and I — were the founding members. With this meeting, we launched one of most influential civil rights movements in the state of Virginia. In my view, we jump-started our own Manhattan Project.

Remember. We were war children. We had experienced World War II and the Korean Conflict. In our minds, we developed the ability to offer critiques and analyze secret missions — spy concepts. I had listened to war stories via battery-operated radios. Instead of playing cowboys and Indians, we played soldiers and spies. When I became involved with this project at school, it became a top-secret project whereby only a few trusted and tested friends would be invited to join.

Each selected student had to pass a litmus test. Our inner circle would have to be totally trustworthy in order for us to succeed. There would be no space for the slightest error. Everything had to be planned as minute as a gnat’s eyebrow. We were on a very dangerous mission.

We knew that we would be navigating “uncharted waters.” No group of students had ever pulled off such a feat. What did we plan to do? The dangerous task we sought to undertake was to stage a student strike to protest the inequalities at our high school: the segregated Robert Russa Moton High School, in Prince Edward County, Farmville, Virginia!! Our objective? Simple!! We wanted a new building to replace the tar paper shacks.

I understood why Barbara Johns needed our help. You see, within this segregated community of colored folk, we had to deal with the many Judases among us. I felt a parallel between our situation and the movie Lawrence of Arabia. We had to unite persons who, at times, did not get along with each other and who, at times, did not really like each other. Our challenge was to bring enough people together in order to defeat a common foe. That foe was the oligarchy!!!!

Our high school principal, Mr. M. Boyd Jones, has to bear some responsibility for our unification effort at the high school. His leadership skills included hiring a staff that taught my twin sister and me how to operate within the confines of our society. In other words, we learned to be leaders without showing up on the radar screen. It was like the old story about seeing a duck gliding over the water; its feet moving rapidly below the surface could not be seen — unless the water was clear. We even practiced, at times, the old saying: “Never let your right hand know what your left hand is doing.”

A long history of discrimination was against us. The colored students in Prince Edward County had been programmed for failure from day one of the inception of public education there. Inequality had been so pervasive that we felt it bordered on being crimes against human beings.

Although there were more registered colored students in the county at that time, the property value for all of the white schools in the area was in the millions. Comparatively, the property value for the colored students was in the thousands of dollars.

Some white schools were stately, all-brick buildings, and others were constructed of some type of cinder block or stucco. Each building for white students had its own indoor plumbing facility and central heating unit and stood alone on its own property — owned by the county. Each building had multiple classrooms. One elementary school for whites in Farmville stood on the campus of Longwood University. This school was used as a laboratory facility for future teachers. Farmville High was a state-of-the art edifice. This huge, majestic, multi-leveled structure represented Utopia to the ruling class. It had a gymnasium, a cafeteria, a science lab, a huge auditorium, an atrium and an athletic facility that was second to none in the state of Virginia.

In stark contrast, all 13-15 elementary schools for colored children in Prince Edward County were of wood construction and were built on colored church grounds. Students had to use outdoor toilets and drink well water or pump water. There was no central heat; a potbelly stove was the heating source for each site. The principals and teachers at each school had to start their own fires on wintery mornings.

I remember my brother Clem serving as the teacher/principal at New Hope Elementary School. He was in a running battle with Superintendent McIlwaine concerning the mere necessities for students in his one-room wooden school. The parents would have fundraisers in order to purchase school supplies for their children. In fact, Clem often took money out of his pocket to purchase lime to kill the maggots or just to diminish the odor in the outdoor toilets. How many times Clem bought wood so that his students would not be cold!! Truly, this was separate, but equal?

Robert Russa Moton High School, one of the two schools built of brick for colored students, was constructed to accommodate 180 students. When we went on strike in 1951, more than 450 students occupied those grounds. Instead of putting up brick buildings to house the overflow, the oligarchy constructed three tar paper shacks. Unlike the white schools, Moton High had no cafeteria, no gymnasium and no adequate auditorium for proper seating of students.

The three tar paper shacks were in worse shape than housing for chickens, cows and other farm animals. And I should know. I had a job milking 20 cows per day for a German dairy farmer. His cows were housed in a more insulated facility than our temporary school buildings were. Yes, the barns even had running water. There was no plumbing in any of the tar paper shacks.

Our source of heat was one potbelly stove in each classroom in each shack. Students had to run to the main brick building to use the toilet — rain, shine, sleet or snow. These tar paper shacks could not be hidden from the eyes of the public. They were located on Route 15 which ran right through the town of Farmville. Travelers questioned us about a chicken farm being located so close to a school. The travelers were astonished when colored students poured out of those chicken coops to change classes or go home.

In addition to the inadequate facilities, we had to tolerate used buses, used books, used furniture and more. The books had been “endorsed” with racial slurs as they were handed down to the colored students.

We had grown sick and tired of the injustices and the inequalities. Carrie and I attended school board meetings with my brother Clem, our parents or members of the community. The board members would always respond by indicating that things were in the works and we would have to be patient. In fact, the more uncivil board members had the nerve to state “yawl have equality.” In both cases, we were being asked to accept a steady diet of lies and untruths as indications of progress.

J.A. Stokes and his twin sister Carrie Stokes helped lead a student body strike against segregation that led to Virginia’s Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, one of five court cases that was ultimately consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education.

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74 and funded The Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research to produce the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter