Chaos Theory: Amid Pandemic Recovery Efforts, School Leaders Fear Critical Race Furor Will ‘Paralyze’ Teachers

By Linda Jacobson & The 74 Staff | June 28, 2021

Updated July 19

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

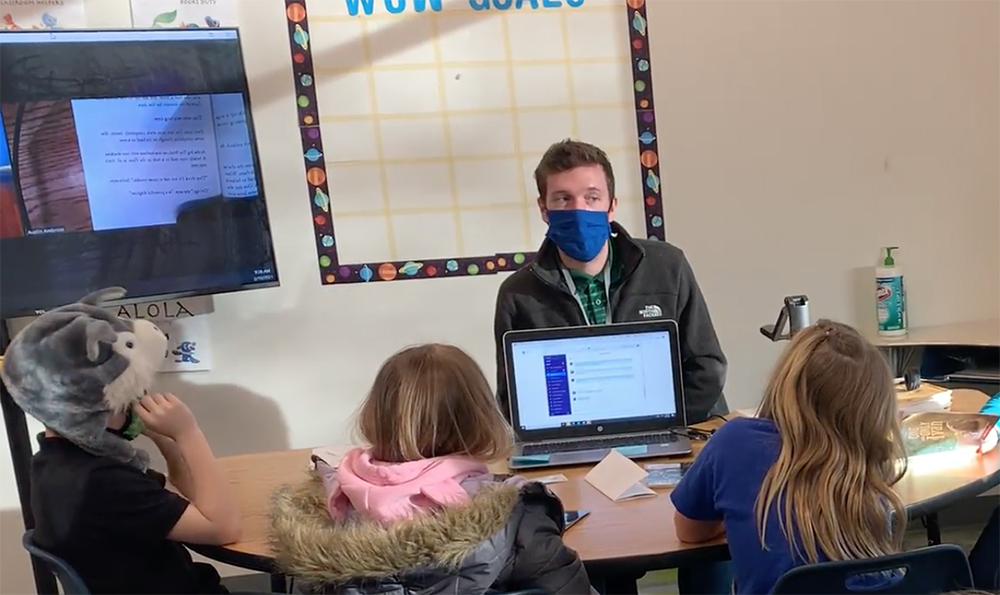

To wind down after a chaotic school year, Austin Ambrose, who teaches third grade in Nampa, Idaho, purchased some fun reads he hoped would keep his students engaged until summer break — and like much good children’s literature, provide a window into another culture.

One title, Dragons in a Bag, tells a Harry Potter-type story set in Brooklyn featuring a young Black boy. But when the book turned up on a social justice website, one family at Gem Prep, a charter school, argued it ran afoul of the state’s new law prohibiting schools from promoting critical race theory.

Under the school’s policy, Ambrose had to offer the student an alternative book to read.

“I told them, ‘I’m only trying to expose your child to different cultures and experiences,’” he said. “These conversations are going to help them when they get into the real world because they are going to meet people who are different from them.”

Idaho is among nine states so far to ban critical race theory — which holds that racism is baked into U.S. systems and institutions to purposely keep people of color at a disadvantage. Lawmakers in at least 20 more states have proposed similar laws to block what they see as a dangerously divisive form of indoctrination. But for many teachers, the backlash feels like a new kind of McCarthyism, one where they fear being harassed, fined or fired for a wide array of classroom activities. It doesn’t help that the clash comes as school leaders are struggling to help students — many of them lagging up to a year behind in core subjects — bounce back from the pandemic. To that end, educators are steering an unprecedented influx of federal funds toward their recovery.

“It’s a huge distraction at a time when we can’t afford a distraction,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “This has been a year the majority of students were not exposed to the kind of learning they should have been exposed to. Now you’re going to paralyze teachers because they are afraid to teach.”

The furor is hard to miss.

The Nevada Family Alliance wants teachers to wear body cameras to prevent them from “going rogue and presenting their own political ideas.” A mother in South Kingston, Rhode Island, filed some 200 public records requests to learn how the district teaches race and gender issues. And Protect Ohio Children, a conservative watchdog group, maintains an “indoctrination map” showing districts influenced by critical race theory.

In suburban St. Louis, tensions over issues of race and curriculum have grown so fraught that educators feared for their physical safety.

Several Rockwood School District administrators had private security officers stationed at their homes. In June, school officials spent nearly $5,000, according to district spokeswoman Mary LaPak, to place private security for two weeks at the home of a district literacy coordinator, who instructed teachers in an April email to remove a lesson plan for a “culture and identity” unit from the online classroom management system “so parents cannot see it.”

In a letter, the local teachers union called on district officials to protect educators from “personal attacks and outright threats of violence” following the backlash. Parents argued the district was teaching critical race theory and “making white kids feel bad about their privilege,” according to the email.

‘Eye of the beholder’

That’s a lot of mileage for an idea most Americans hadn’t even heard of until six months ago.

In that brief span, critical race theory emerged from grad school obscurity to become something of a Rorschach splatter of our anxious political moment. Some see little more than an attempt to reclaim episodes of Black history like the 1921 Tulsa race massacre or the long practice of Jim Crow redlining. For those who decry it, at school board meetings and roadside rallies, it encompasses a host of ills, from anti-bias training to that other “CRT” — culturally responsive teaching, the integration of students’ cultural and ethnic backgrounds into the classroom. Some have lumped social-emotional learning and restorative discipline into the mix.

Because it can be so hard to define, Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian at the University of Pennsylvania, called the dust-up over critical race theory “scarier” than similar controversies, such as the recent clash over teaching The New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project.

“The 1619 Project is a thing you can look up; it’s a very specific document with a curriculum attached to it,” he said. “Critical race theory isn’t in that category. It’s kind of in the eye of the beholder. And if that eye has watched a lot of Fox News, it’s going to behold a lot of critical race theory.”

Fox has used the term more than 1,860 times so far in 2021, according to the Washington Post. And conservative organizations such as No Left Turn continue to highlight schools that focus on students’ racial or gender differences. NBC News found that least 165 such “grassroots” groups have sprung up over the past year, many with ties to GOP strategists.

Republicans see it as a winning strategy they can ride into the 2022 midterms. Celinda Lake, a Democratic pollster, expects the fight to keep playing out in school board elections.

“We’ve gone through different waves, but school board races are very unequal terrain because the right spends so much time focused on them,” she said.

In Virginia’s Loudoun County Public Schools, a conservative group, Fight for Schools, has launched a recall effort over board members’ support for equity-related initiatives A video of Lilit Vanetsyan, an educator in neighboring Fairfax County Public Schools, went viral when she appeared before the Loudoun board to declare that classrooms had become “indoctrination camps.” While the Fairfax district confirmed she is an employee, she also runs a Teachers_for_Trump Instagram account and is a correspondent for the Right Side Broadcasting Network.

In Tennessee, a chapter of Moms for Liberty, a group seeking more parental influence over school policies, opposes teachers’ use of the autobiography Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story. Bridges wrote the 2009 book, which is aimed at second graders, about her experience as one of the first Black students to attend all-white schools in New Orleans. According to local news reports, the group objected to the book showing a crowd of “angry white people” protesting integration.

When parents equate key aspects of the civil rights movement with critical race theory, they “have become very confused,” said Erika Sanzi, the director of outreach at Parents Defending Education, a nonprofit at the center of efforts to resist what they see as “harmful” political agendas in the classroom. (The organization’s website does not identify funders, and Nicole Neily, the group’s president, declined to to name them out of concern for “donor privacy.”)

Sanzi said she’s not necessarily in favor of the GOP-backed legislation because she’s “still hanging on to the belief that we beat bad ideas with better ideas.” But she does question the messages some young elementary students are getting about their “whiteness.”

At an elementary school in Bellevue, Washington, for example, a school improvement plan for the 2020-21 school year said that students would “have explicit conversations about race, equity, and access,” and that fourth and fifth graders would be responsible for implementing schoolwide anti-racist strategies. The plan has since expired and the district said it allows parents to opt their children out of “identity-related discussions.”

“These are children who believe in Santa Claus and put their teeth under their pillow,” Sanzi said.

At Phoenix Middle School outside Columbus, Ohio, the confusion ran so deep that two families asked to remove their children from a course that focuses on critical thinking.

To their parents, that sounded a lot like critical race theory.

In a February email to the school’s principal, one father who pulled his child from class said “he didn’t want his kid feeling guilty about ‘Marxist critical race theory,’” recalled Robert Estice, who teaches the required course. The class syllabus has no mention of Marxism or critical racial theory. For seventh grade, course themes include “How do I know what I know?” and “How do I interact with others to understand their perspectives?”

“I don’t want to put ideas in kids’ heads that aren’t their own ideas — that they wouldn’t have come to themselves,” Estice said.

Some educators wonder whether the laws will take away a powerful tool that teachers have to connect with students — their own personal stories.

“I was a teacher, and one of the things I loved the most was the freedom to teach,” said Tramelle Howard, a board member in the East Baton Rouge Parish School System in Louisiana, where a bill curtailing the teaching of critical race theory failed to advance in the legislature this session. “I did not shy away from my lived experience. I had white male students in my classes, and it wasn’t my job to get them to think a certain way, but to think critically.”

‘Intentional agenda’

Little of this has anything to do with actual critical race theory, the legal term coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1970s. It has become synonymous with a kind of racism that applies to institutions rather than individuals. It could, for example, describe police departments that disproportionately apply excessive force against African Americans.

In fact, it was one of these moments, the murder of George Floyd by a white officer in May 2020, that is most responsible for pushing critical race theory into the public consciousness. The cell phone video of Floyd’s death taken by a Black teen prompted months of protests and led many school leaders to take public stands condemning racism and calling out “white privilege.”

Some of those efforts prompted outcries not only from parents, but educators. Teachers in a New Jersey district complained in March about being required to participate in what they described as “insulting” anti-bias training. One white teacher reportedly said a presenter told her she was a “inherently racist” and a “white supremacist.”

And in the Virginia Beach Public Schools, where some board members are pushing to ban critical race theory, Superintendent Aaron Spence agreed that his district went too far when literacy coaches attended a February training in which a video speaker said white educators should say “of course I’m racist.” Such approaches, he said, alienate teachers when “the whole goal of equity is to keep everybody in the room.”

With public comments over critical race theory dominating the last three board meetings and staff members frequently responding to calls and emails from residents, he called the uproar an “intentional agenda of distraction” that “takes us away from the real work of addressing the challenges we face in public education.”

In September, former President Donald Trump put his stamp on the issue with an executive order banning federal employees from receiving any training about critical race theory, further contributing to the perception that it promotes anti-American ideas. President Joe Biden reversed the order, but its language became a template for state bills to come.

Just last week, Republicans on the House education committee peppered Education Secretary Miguel Cardona with questions about critical race theory, specifically a notice for a civics and history grant program that references the 1619 Project and the work of Boston University’s Ibram X. Kendi, a leading author in the field. (The department has since removed the references.)

Named last year as one of Time’s 100 most influential people, Kendi won the National Book Award for Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. With such accolades, he is among speakers who can command over $20,000 an hour to address school districts on the issue. Kendi, like others, argues that everyone is born into a society founded on racism and that it requires intentional steps to reverse disparities. He advocates for a constitutional amendment, which would create an anti-racism agency to evaluate all local, state and federal policies to ensure they don’t contribute to inequity.

During the virtual hearing, some committee members tried to get Cardona to denounce Kendi’s work. “Do you realize how radical and how out of touch this guy is?” Rep. Glenn Grothman of Wisconsin asked.

Virginia Rep. Bob Good pushed Cardona to ensure that the federal government wouldn’t legally challenge state laws banning critical race theory. While Good was speaking, someone shouted “racist” and New Jersey Democrat Donald Norcross’s name briefly showed on the screen. Chairman Bobby Scott, D-Va., later noted the “inappropriate comment” and asked the members to respect each other.

Cardona said multiple times the issue has become politicized and the department doesn’t dictate curriculum, but that he trusts teachers to navigate these issues and believes culturally responsive teaching “builds community.”

Scoring ‘political points’

In states where legislation has already passed, some educators are questioning how they’ll be able to address controversial topics this fall.

“How can we learn about U.S. history without feeling distress at times?” asked Eddie Walsh, an eighth-grade social studies teacher at Memphis Grizzlies Preparatory Charter School in Tennessee, one of the states that has passed anti-critical race theory legislation. “Our goal as educators isn’t to make kids guilty, but we also can’t lie to them or omit the truth when it comes to our past.”

In Texas, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott signed legislation this month that allows teachers to cover the history of white supremacy, including topics such as the Ku Klux Klan and the eugenics movement, which involved the forced sterilization of Black women. But it forbids instruction from causing students to “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or another form of psychological distress” because of their race or sex.

Asia Klekowicz and Ryan York, co-CEOs of The Gathering Place, a San Antonio charter school with a focus on social justice, know they could be sued.

“There is a long history in the U.S. of laws being written as a way to score political points.” York said. “We welcome challenges to the way we [address these subjects].”

‘Thousands of critical conversations’

So, where do we go from here? Legislation designed to suppress the controversial philosophy’s influence is problematic for a few reasons, said Matthew Shaw, an associate law professor at Vanderbilt University. First, he said, the laws are difficult to enforce. And second, they’ve only created greater interest in the ideas they seek to wipe out.

“The irony is that trying to ban or limit critical race theory in conversations in such a public, blunt, legalistic manner has sparked thousands of critical conversations,” he said.

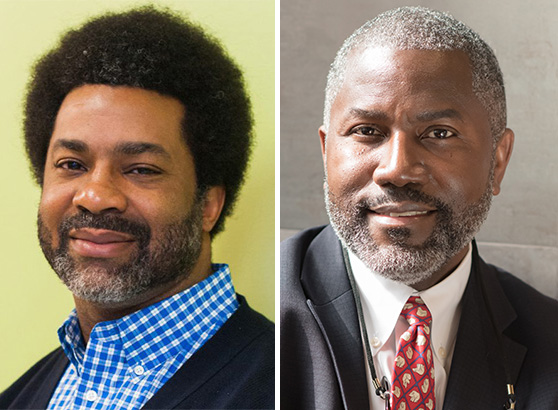

One of the more thoughtful exchanges occurred last week, when two Black educators addressed the National Charter School Conference. Ian Rowe, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, called the debate a “massive distraction” from the fact that too many students — including white children — read below grade level.

“We want to create equality of opportunity for all our kids. Literacy has to be the anchor of that,” said Rowe, who sits on the board of the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism, which aims to unite people based on “common humanity.” “I don’t want the whole hullabaloo around critical race theory to detract from something that is holding back kids of all races.”

He said students should know the history of racial oppression, including the Tulsa race massacre, alongside the “stories of racial resilience,” such as how Booker T. Washington founded more than 5,000 schools in Black communities throughout the South with Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears. And teachers should introduce critical race theory alongside ideas that challenge it. The problem, he added, is when it’s presented as a “sole theology.”

But at the same session, Sharif El-Mekki, CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, described the backlash to critical race theory as “absolute hysteria.” He added that focusing on successful Black people who “made it” ignores the reality of why they had to be resilient in the first place.

“That is a pathway to the dark side without the full story,” he said.

—Reporters Beth Hawkins, Mark Keierleber, Asher Lehrer-Small, Kevin Mahnken, Marianna McMurdock, Bekah McNeel and Patrick O’Donnell contributed to this report.

Clarification: An earlier version of this story reported that Rockwood School District officials spent $2,500 to place private security guards outside two administrators’ homes. That expenditure was related to a district controversy involving the removal of the “thin blue line” flag — a police solidarity symbol that has become associated with white supremacy — from a high school team’s baseball cap.

Lead images: Getty Images, Teaching for Change/Flickr and marisaoste/Instagram

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter