Tulsa Commits to Teaching ‘Hard History’ After State Restricts Antiracist Instruction

By Asher Lehrer-Small | June 1, 2021

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

When Tulsa, Oklahoma fifth-grade teacher Akela Leach began her lesson this May on the race massacre that took place in the city’s Greenwood District 100 years earlier, her young students knew they were entering contentious curricular territory.

The state of Oklahoma had recently passed a controversial bill that observers described as an “antiracism teaching ban,” part of a wave of legislation from Republican lawmakers across the country to scale back discussion of systemic racism in the classroom.

At the outset of the lesson, a student raised her hand. A family member had told her that the new law might prevent them from talking about the Tulsa Race Massacre in school. It wouldn’t, Leach told her students, explaining that the 1921 event was a key element of their city’s history.

“They literally cheered that we were going to still learn it,” remembers the social studies teacher.

Further, it seemed the political milieu deepened students’ interest in the lesson.

“I’m learning something that someone doesn’t want me to learn,” Leach’s fifth-graders thought, “so this must be really, really important.”

“We know forbidden information,” one student exclaimed with glee.

Educators in the city have been preparing to tackle the topic for over a year. In February 2020, state lawmakers moved to add lessons on the 1921 race massacre to state curriculum standards. Last summer, Tulsa Public Schools held a five-part webinar series in collaboration with the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission to help teachers learn to confidently lead conversations on the grim event. And the district recently rolled out new resources for educators, complete with ready-made units and lesson plans.

As of this May, Tulsa public school students in grades 3 to 12 now learn about the violent episode in social studies class.

As those lessons were first beginning to unfold in classrooms across the city, and as the race massacre’s June 1, 2021 centennial was fast approaching, state lawmakers took up and quickly passed a bill to ensure that no teacher would make a student feel that “by virtue of his or her race or sex, (he or she) bears responsibility for actions committed in the past.”

“Unfortunate is really much too weak a word” to describe the timing, Erica Townsend-Bell, associate professor at Oklahoma State University and director of the school’s Center for Africana Studies, told The 74.

“It’s really troubling … that it is signed as we come to the 100-year commemoration and remembrance of the Tulsa Race Massacre.”

Over the Memorial Day weekend, the city marked the anniversary with a ribbon-cutting to the Pathway to Hope at Greenwood and a Monday night candlelight vigil. On Tuesday, Tulsans welcomed President Joe Biden to visit with living survivors and descendents.

Back in the classroom, as Leach ventured into this history, she said, her fifth-graders rose to the occasion. They discussed Jim Crow segregation and why Black Tulsans, in order to prosper, had to create their own thriving community. One student analogized the roiling racism of early 20th-century Tulsa to a volcano with pressure building up and up until it finally erupted in 1921 in white violence and destruction.

“They were able to tackle something that many people would think would be too heavy for them,” said Leach. “But it really isn’t.”

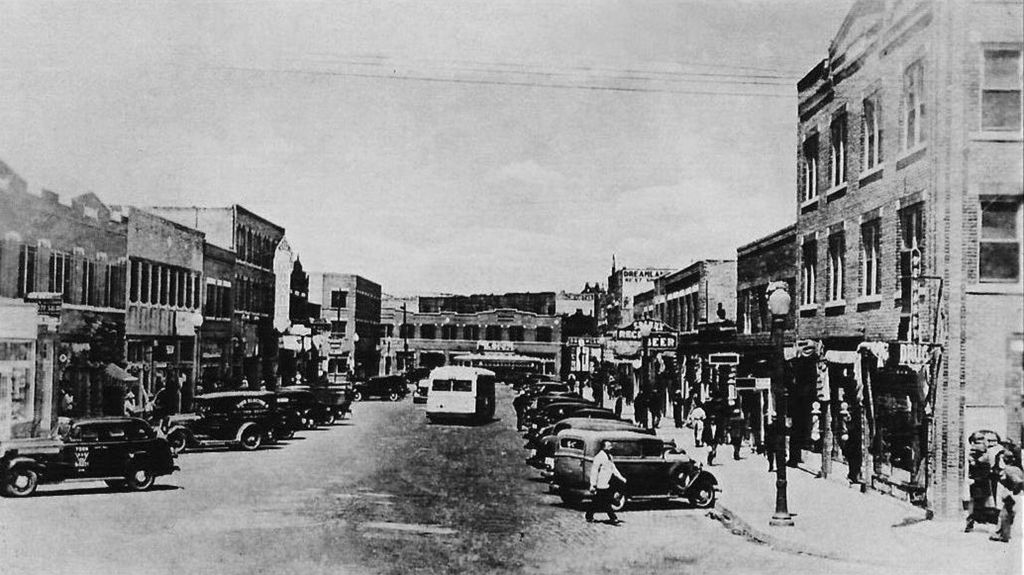

Teachers, she says, have a responsibility to address difficult topics — “hard history,” Leach calls it — even if it’s uncomfortable. In the 1921 massacre, a white mob killed hundreds of residents in Tulsa’s Greenwood district and destroyed banks, doctors’ offices, barbershops and over 1,250 residences, erasing years of Black success.

It’s about “teaching the truth of what happened and not just the surface level,” she said, even if it shows our country or our ancestors in an ugly light.

District leadership seems to agree.

“There is hard history that we need to confront,” Tulsa schools Deputy Superintendent Paula Shannon told The 74, adding that the recently signed statewide legislation “doesn’t impact us at all.”

“We’ve worked very hard to build a culturally responsive curriculum that is not mired in politics,” she said. “And so we’re going to continue to do what we believe our kids deserve.”

Superintendent Deborah Gist, a Tulsa native who grew up attending the city’s public schools, said that she didn’t learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre until she was an adult living halfway across the country in Florida. “Our team will never let that happen again,” Gist wrote in a tweet.

Critical race theory, the controversy du jour outlawed by the recent spate of laws coming from Republican-held legislatures, is not an ideology, said Townsend-Bell, the Oklahoma State University professor, but a lens of thinking that considers how political systems are “racialized and exclude certain populations.”

The Oklahoma law does not expressly mention critical race theory. It also specifies that no content laid out in the Oklahoma Academic Standards, as the Tulsa Race Massacre lessons are, would be prohibited.

While Townsend-Bell sees how the bill may have been intended to “chill” educators’ efforts to teach the uglier sides of the state’s past, she says the actual content of the law does no such thing. Its focus is on ensuring students don’t feel guilty or culpable for historical events, but Townsend-Bell said teachers looking to grapple with such episodes ought to focus “primarily not on individuals, but on institution, systems and policies.”

In other words, explained Leach, the Tulsa fifth-grade teacher, the law is “more about how you’re teaching something, versus just the topic itself.”

She says the bill seems to be “written for a problem that didn’t really seem to exist.”

“I don’t think that it’s the norm that teachers are going around and telling students that they’re responsible for racism, or telling them that they are inherently racist, because they’re white,” she told The 74.

The elementary educator was part of the team that developed lesson plans on the 1921 race massacre, and she emphasizes that the content is age appropriate and thoroughly vetted.

In fifth-grade classrooms, discussion focuses on resilience and rebuilding Greenwood. The predominantly African American district was known as America’s “Black Wall Street” thanks to its prosperity. Students learn about how its residents salvaged elements of the neighborhood and rebuilt their livelihoods, albeit with untold lasting damage, after the violent episode that reduced it to rubble.

Leach explained that a team of teachers, district leaders and curriculum experts carefully reviewed each unit. They considered how lessons would feel for people from every imaginable perspective: a new teacher, a white teacher instructing mostly Black students, a Black student, a Latino student, a white student and more.

“[The curriculum] was designed to be inclusive,” she explained. Her classroom has a majority of white students, but also includes Black and Latino students.

Thanks to the district’s careful planning and the training opportunities offered to staff, Leach feels confident that Oklahoma’s new law will not affect how she or other Tulsa teachers approach their lessons. But she could imagine that educators with fewer supports or less confidence in the content area might feel differently.

“Someone who was hesitant to teach this or doesn’t feel comfortable teaching it … it can make them fearful,” said Leach. “It kind of gives people an out.”

Oklahoma state Representative Kevin West, the bill’s sponsor, told The 74 that it will be up to the state education department to implement the provisions of the bill. They will specify who decides whether a teacher is acting in violation of the law and what the repercussions might be, he said. That rule-making process will begin in the fall, Annette Price, spokeswoman for the Oklahoma State Department of Education, wrote in an email to The 74.

“Until then, the bill stands on its own for districts to follow,” she said.

But while Leach worries that the threat of repercussions could deter some teachers from covering tough topics like the Tulsa Race Massacre, Townsend-Bell wonders whether it might have the opposite effect and actually motivate teachers to prepare more thoroughly for such lessons, out of fear that tactless classroom leadership could land them in violation of the law.

“I could imagine a world in which, because of this bill, folks feel a little bit more compelled to make sure that they know what they’re talking about, to inform themselves a little bit better, before they walk into the classroom to share that with the student population,” said the professor.

“What we could actually ironically see is some better teaching around these histories because of this concern that, ‘I don’t want to mess it up.’”

Lead Image: The Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, a prosperous Black enclave, was reduced to rubble after the 1921 race massacre. (Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter