School Choice Backers See Opening in COVID Chaos, Even as Culture War Issues Threaten to Fracture Coalition

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As 2022 unfolds in statehouses nationwide, lawmakers have their sights squarely set on parents like Marta Mac Ban.

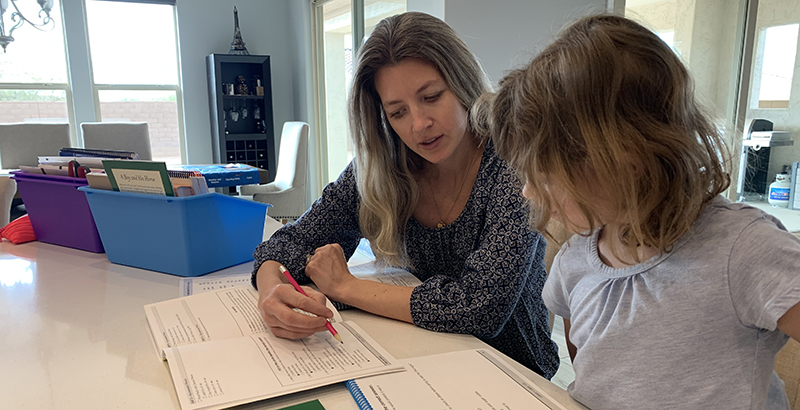

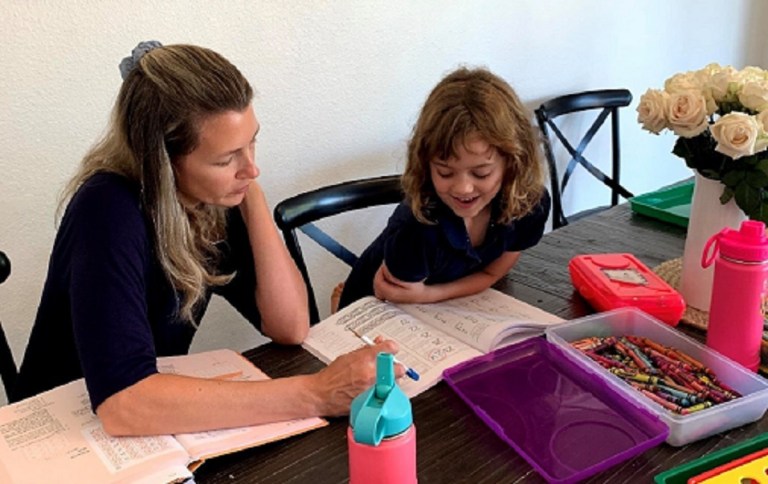

In 2019, the Arizona mother of two sent her older daughter off to kindergarten in Scottsdale, Ariz.’s Cave Creek Unified School District.

But after Mac Ban saw the district’s tepid response to the pandemic, she started home-schooling her at taxpayer expense. Arizona’s publicly funded Empowerment Scholarship Account now underwrites her kids’ education.

Similar scholarship accounts could soon do the same for millions of other students nationwide as a new raft of proposed laws makes its way through state legislative sessions this month, buoyed by parent anger at district policies.

Mac Ban balked at homeschooling at first, envisioning herself isolated and sitting at home with her kids for most of the week. But the more she learned, the more attractive it seemed. After she disenrolled her daughter from a district school and applied for the ESA, the child began learning lessons from the “classical Christian” Highlands Latin Cottage School of Phoenix Valley. Her total bill comes to about $200 per month.

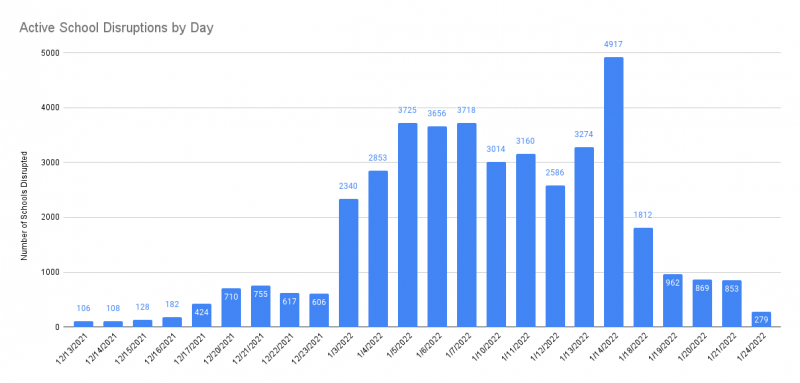

School choice advocates see hope in stories like these. As the omicron variant continues to wreak havoc on schools’ normal procedures and parents lose patience with lockdowns, quarantines, and mask and vaccine mandates — as well as curricula that some view as politically charged — advocates hope that more parents like Mac Ban will insist that taxpayers help pay for their kids’ educations outside of neighborhood public schools.

School choice has always relied on a fragile left-right coalition, mostly between Black and Latino activists and centrist-to-conservative legislators pushing to rebalance the power structure of public schooling. That coalition has weakened over the past few years. But scholars such as Paul Peterson, who directs Harvard University’s Program on Education Policy and Governance, now see an opening.

“A couple of years ago, there was a feeling in the country that opposition to school choice was on the rise,” he told attendees at a recent virtual conference at Harvard. “Some of the coalition and backing for school choice was eroding and the movement, perhaps, was breaking down. But in light of the pandemic, there is a contrary feeling emerging in the country today: We are finding the passage of new school choice legislation in states across the country, new tax credit programs, new education savings accounts programs, expanded charter school programs. There’s a lot of interest in opening up to parents opportunities that haven’t existed in the past.”

While culture war issues like critical race theory could upend that coalition once again, the mood at Harvard was one of optimism. Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, who now chairs the nonprofit reform group ExcelinEd, pointed to recent legislative successes in Missouri, West Virginia and Kentucky. “The legislatures are on fire right now for these kinds of things, so it’s all good. And I don’t see it going away. I really don’t.”

Choice advocates got an unexpected boost in November when Republican Glenn Youngkin won the governor’s race in increasingly purple Virginia, beating establishment Democrat Terry McAuliffe by 2.4 percentage points. Youngkin pulled off the surprisingly solid victory in part by tapping into parents’ anger about public education, giving a voice to thousands who felt schools haven’t risen to the challenge of basic education during the pandemic. McAuliffe, a former advisor to President Bill Clinton, didn’t help his case during the campaign when, discussing recent conflicts over anti-racist education, said, “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.”

Derrell Bradford, president of the education advocacy group 50CAN, told attendees at the Harvard conference that McAuliffe’s mistake was displaying “just a complete and utter tone-deafness” to parents’ experiences. “After a year-and-a-half, almost two years, of incredibly disrupted institutional experience that was visited on almost every family in the country, you probably shouldn’t say something like ‘Parents don’t matter.’ You can make it a school choice lesson, but there’s a lesson there about treating people poorly who’ve been treated poorly.”

Republican strategists such as Christopher Rufo, who last year ignited the raucous campaign to fight critical race theory, now talks of families’ “fundamental right to exit” public schools that don’t sync with their beliefs.

As the omicron variant dominates and infection rates begin to slow, vaccine requirements for even the youngest children could anger parents further. And while many parents have fought for a return to in-person learning, others are clamoring for remote options amid the recent surge: Recent polls find that about six in 10 parents of school-aged children favor virtual learning.

For the past year or more, parents have been voting with their feet: Public schools have shed millions of students, recent data show. In New York City, the nation’s largest system, 50,000 fewer students attended last fall than two years earlier, The New York Times reported in October — a 4.5 percent decline.

Chicago Public Schools in October had lost about 10,000 students over the past school year, a 3 percent drop. Overall enrollment was down by nearly 25,000 students over two years.

Across California, the nation’s most populous state, educators are awaiting updated figures, but estimated enrollment has dropped since 2018-19 by about nearly 184,000 students, or about 3 percent, CalMatters reported earlier this month.

A Tyton Partners survey issued in July found that since the beginning of the pandemic, an estimated 17.5 percent of children have switched schools at least once, 75 percent more than in average years. And nearly 80 percent of parents said they’d be “more active in shaping their child’s education” in the future.

At the Harvard conference, Bradford said school closures during the pandemic in 2020 suddenly brought the system’s failures into “high and broad relief” for 60 million families — especially families of color and low-income families.

“If you are a Black kid in New York City, you were the least important person in America for the last two years,” he said. “And if you were a teacher in that system, you were the most important person in America during that time. And we made it very clear and explicit that that was the case. We have a system that is built upon that foundation, with those priorities. And it couldn’t get the majority of kids reading proficiently before the pandemic.”

Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, one of the nation’s largest teachers unions, said she actually expected “a far higher percentage of families” to opt out of their neighborhood schools, given fears about COVID and “the volatile debates about safety protocols” over the past two years.

That a mass exodus didn’t happen, she added, “says to me that families are valuing public schools and what a good public school is for: academics, of course, but [also] as centers of communities, where kids eat healthy meals, access health care, and find social and emotional supports.”

For her part, Weingarten has pushed to “have a different conversation” about school choice, one focused on what has worked in private settings during the pandemic — but that also treats public schools less as a commodity that families can buy than as a public good.

“We’re experiencing a crisis in our democracy in which our public schools have a really important role,” she said. “Why not try to figure out how to make this year, regardless of where we are, a year of recovery and revival for our kids and not have a year of winners and losers?”

As 2022 progresses, that seems unlikely.

EdChoice’s director of national research, Michael McShane, recently pointed out that since the beginning of 2021, more than a dozen states have created or expanded school choice programs. The group now says 18 states enacted seven new choice programs and expanded 21 existing ones. Robert Enlow, the group’s CEO, called 2021 “without a doubt” the biggest year for school choice since EdChoice has been tracking it.

In an interview, McShane said that until recently he was expecting upcoming state legislative sessions in 2022 to be “pretty quiet” on topics like school choice. “I think now that there is going to be a lot going on.”

Part of the reason may be the billions in COVID relief funds that school districts have received to keep them afloat, he said: “In politics, things happen easier when there’s a bunch of money sloshing around.”

On the one hand, the money softens the blow of all of the student departures — but it also makes it harder for school districts to complain to state lawmakers about the effects of often small choice programs that draw students out of the public system. “This program that’s spending $25 million across the entire state, how can you possibly have a problem with it when you just got $2 billion from the feds?” he said.

As legislative sessions begin in several states, choice is on lawmakers’ minds. In Kentucky last week, lawmakers introduced an expanded school choice bill that would give families tuition assistance for private education.

In Missouri, lawmakers last year approved a tax credit to fund a private-school tuition education savings account, and lawmakers are now pushing to expand the program before it even takes effect. They’ve proposed lifting a $25 million funding cap and dropping requirements that families who participate live in a city with at least 30,000 residents.

Youngkin, just a few days into his term in Virginia, backed a GOP-led effort in the narrowly divided state legislature that would expand the number of charter schools from fewer than 10 to about 200. The bill would allow the state Board of Education to create regional charter school “divisions” with the power to approve new charter schools, despite opposition from localities.

Higher graduation rates … or winning the culture war?

Concerns about parents’ role in their kids’ education played a “huge role” in Youngkin’s Virginia election victory, McShane said, but more broadly, parents “want to be back to normal now. And the fact that things aren’t back to normal is leading to a lot of discontent.”

Whether from rolling quarantines, mask or vaccine mandates, he said, “I think all of this stuff is just going to continue to roil schools, and you’re going to have people that just want out — they don’t want their school’s vaccine policy to be set by 51 percent of their neighbors. They’re going to want to have the option to go to a school where it’s decided at the school level.”

Whether the current push for school choice plays out in both blue and red states, however, remains an open question.

Most of the recent legislation has prevailed in reliably Republican-controlled legislatures, even if a few of the successes came with the endorsement of a Democratic governors, as in West Virginia — or despite a governor’s veto, as in Kentucky.

In reliably blue Illinois, Gov. J.B. Pritzker, who was elected in 2018, campaigned on a promise to slash funding for a tax credit scholarship. But once he was elected, “he actually signed a bill to strengthen it modestly,” said Greg Richmond, a longtime school choice advocate who now leads the Archdiocese of Chicago Catholic Schools.

“It seems to be one these classic cases where it’s easy to say anything when you’re running for office, but when you get into office, you find out voters have an interest in the program you want to eliminate — you start to change your mind about it a little bit,” he said. “So he backed off.”

But these days, Richmond said, even private Catholic school parents are talking about exercising their right to leave schools over concerns about so-called critical race theory or enforcing mask and vaccine mandates — the latter two are required by an executive order signed by Pritzker, and also apply to private school students.

“Some people got very mad and wrote to me: ‘We should be fighting this [mandate]. This is tyranny. This is against God — this is Satan. If you don’t change it, I’m going to pull my kids out of your school and send them to public schools,’” Richmond recalled. “I was like, ‘What? That makes no sense.’”

But the more he thought about it, the more he realized that these parents “were paying tuition in order to avoid that stuff.”

The trend toward ideological reasons for opting out is worrying for the larger school choice community, said Richmond, who from 2005 to 2019 was CEO of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers. He was also the founding chairman of the Illinois State Charter School Commission.

A decade ago, he said, “you could get bipartisan support for statements like, ‘Parents ought to be able to choose from a range of options that best meet the needs of their kids.’ Now conservatives aren’t saying stuff like that anymore. It’s like, ‘We’ve got to do this to save America from the Satanic clutch of CRT.’”

The new rhetoric, he said, is “not in pursuit of higher graduation rates and test scores,” he said. It’s “choice in pursuit of winning the culture war.”

That risks alienating politically moderate or left-leaning teachers and parents who would otherwise support choice. If the only politicians who support school choice also happen to be hard-right culture warriors, “school board moms,” or Trump supporters, “that might be an Achilles heel of all this,” he said.

‘Every kid is unique’

Mac Ban, the Phoenix mother, said part of her decision to homeschool actually revolved around what she saw as a social justice sensibility creeping into the district — she has heard examples of math word problems that included references to white subjects stealing from Black subjects. Mac Ban said such ideas are “not appropriate for an elementary school student.”

Young children, she said, “need to learn the basics. They need to learn the fundamental things, and they need to learn to think on their own, to think critically, not be told that they are an oppressor.”

Mac Ban, a first-generation American — her family came to the U.S. from Communist-controlled Poland in the 1970s — said she was able to qualify for Arizona’s ESA because her younger daughter had an individualized education plan due to a diagnosed speech delay. Simply being in the same family qualified her older sister, the kindergartner, for ESA funds as well.

Her initial concern that she and her kids would be isolated quickly passed when they joined the Highlands Latin community. “By homeschooling, I don’t mean that I’m just sitting here with my daughters every day and we don’t see anyone …We do all kinds of group lessons, activities. I’m never home. We’re always out and about, doing different things,” she said.

Mac Ban likes having the ability to choose what lessons and subjects her daughter — now a second-grader — pursues.

“Every kid is unique, and the parents know what’s best for their child, ultimately,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter