An Experiment at the Crossroads: In Year Two, Pandemic Pods ‘Find Their Legs’ — and Face Their Limitations. Will They Endure Beyond COVID-19?

By Linda Jacobson | October 4, 2021

Updated October 5

Megan Monsour knew she was taking a risk last year when she pulled her two sons out of the Wichita, Kansas, district and enrolled them in Green Gate, a nature-focused microschool. Not only did she fret over her sons’ exposure to COVID-19, but wondered whether they’d get the attention they needed for persistent reading difficulties.

But then Green Gate arranged for a dyslexia specialist to tutor the boys during the school day — something the district wouldn’t do even though the Monsours were willing to pay for it.

“Although we believe in and want to support public schools, it was frustrating that there was no flexibility to have the tutoring I wanted,” Monsour said. Now, after a year in the program, she said their reading has improved. “I also like the independence and autonomy Green Gate teaches. They have a lot of time outside and I think children need more recess and chances to have hands-on learning.”

The Monsour boys are two of the roughly 2,400 students who left the Wichita district last year and among thousands across the country who aren’t returning to public schools this fall. While the pandemic provided the initial spark behind the growth of pods — and remains an important catalyst — parents say their reasons for joining have expanded as the concept has taken root. Those reasons are as varied as resistance to mask mandates, a desire for culturally relevant education and frustration with services their children were receiving in public schools. As the movement enters its second school year, many parents who formed small pods last fall are also recognizing their limitations and are now linking up with larger, more-established networks of homeschoolers for support.

“Now that they have a year under their belt, they are starting to find their legs,” said Kija Gray, a coach who advises mostly Black families in Detroit that have left public schools for homeschooling and pods. A year ago, she said parents were “really super nervous” about their decisions. Now she hears more excitement in their voices. “What I think they found was community.”

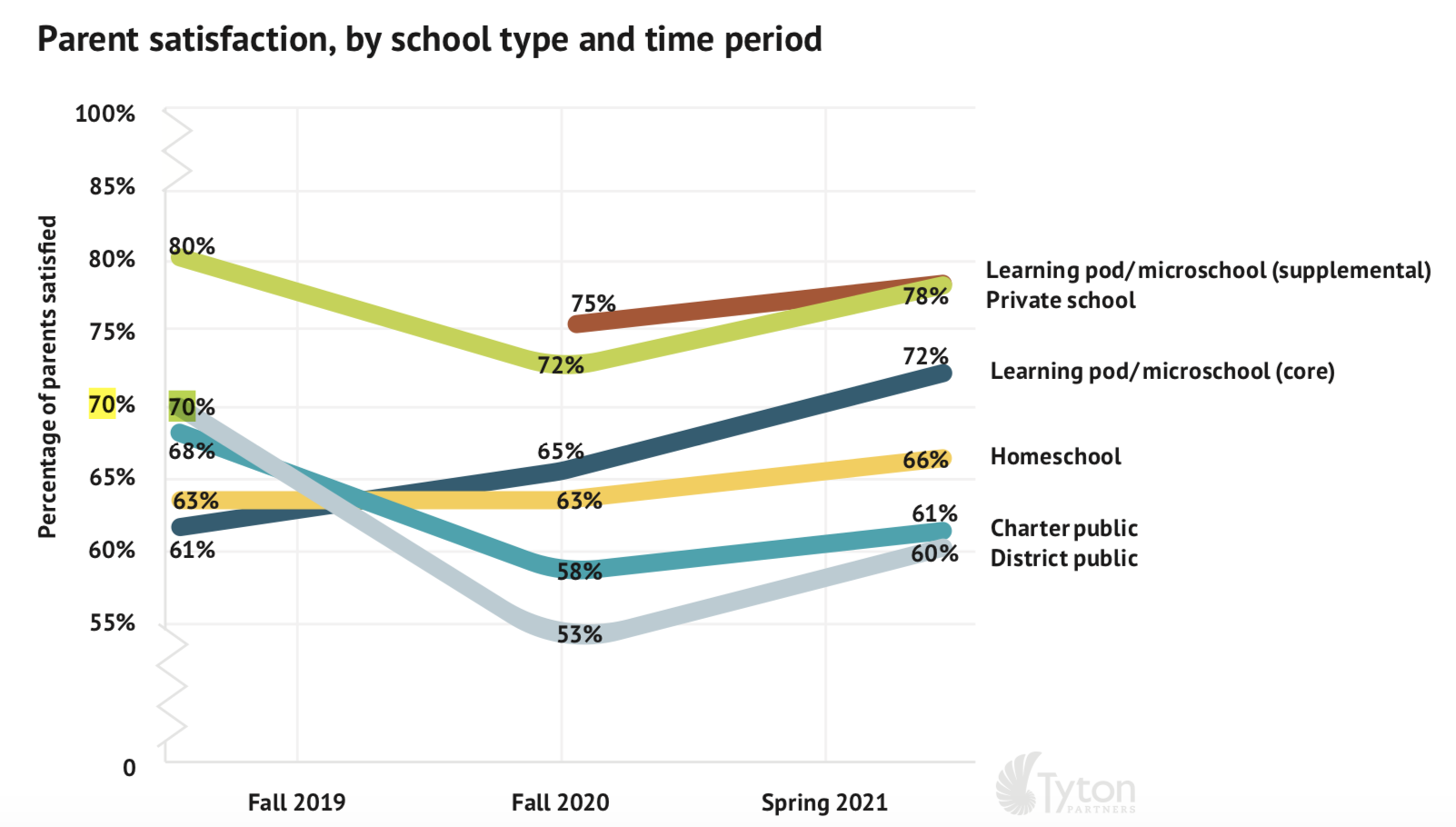

In July, Tyton Partners, a consulting organization, released a survey on the durability of such alternative schooling models. Of the 2,500 parents responding, three-quarters of those who chose pods last school year — like the Monsours — planned to stick with them. The authors estimated that enrollment in pods and microschools, which are larger but still offer personalized instruction, would reach 1.5 million this fall.

But some of the skepticism that initially greeted the movement remains. The costs and logistics involved in maintaining pods, especially for families struggling financially or parents returning to work outside of the home, continue to present challenges.

“They’re not likely to scale substantially post-pandemic,” said Thomas Toch, director of Georgetown University’s FutureEd. Pods, he said, were a “rational response” to school closures, but “free public schools, we learned …, play a central role in most families’ lives, their very uneven quality notwithstanding.”

Critics of the pod movement warned last year that they would ultimately hurt public schools by taking away student funding. But some districts this fall have tried to reverse the trend and lure back those who fled public schools last year. In the Alexandria, Virginia district, staff members have made phone calls and sent postcards, texts and emails to those who left for homeschooling or private schools. In Wichita, the district contacted 115 families, including those in pods or microschools. Half have returned, said spokeswoman Susan Arensman.

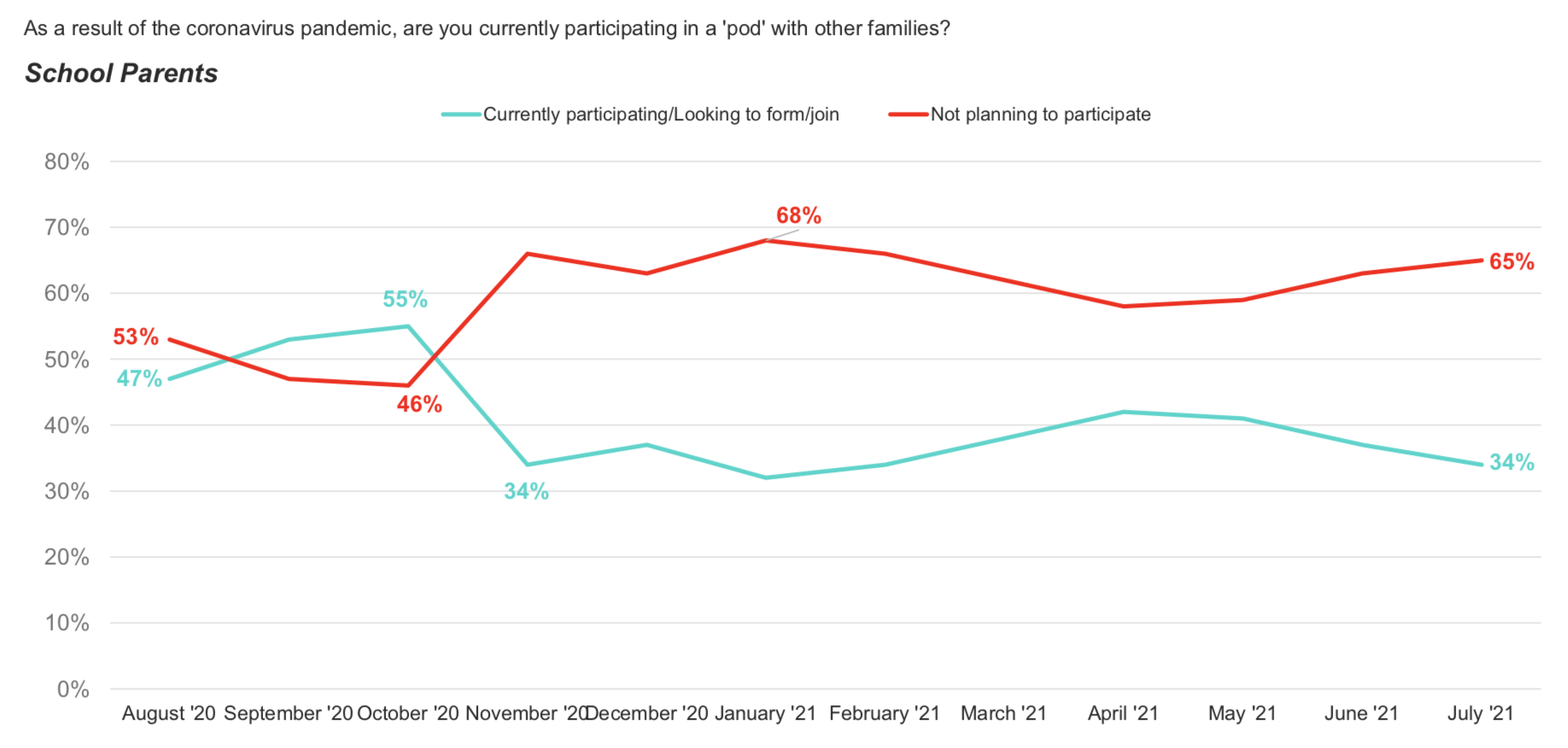

Trend data from EdChoice and Morning Consult shows participation and interest in pods peaked last fall and since then have held constant at about a third of parents. About a quarter of those in pods have left their public schools and about a third who say they are interested in joining one would do so as well. Those who are Black, Hispanic, Democrats, live in urban areas and in the West are among the most likely to participate in pods, while parents who are white, Republican and low-income are among the least likely to show interest, their polling shows.

Privately and publicly funded efforts to lower the costs of pods and microschools are available for those who can’t afford the option. Without such efforts, concerns about pods being a choice only for the more affluent will continue, the Tyton authors warned.

‘Centered on the virus’

School closures drove parents to form pods last year so they could spread the responsibility for teaching — or paying for a teacher — across multiple families. Now some of the restrictions schools put in place to avoid closures are also influencing their decisions.

“The first question I get is, ‘Do you mask?’” said Karla Withrow, who runs EarthChild Explorers, an outdoor program serving preschoolers and grades K-1 in a large Riverside County park in southern California. She doesn’t require masks, and the students are always outside, where transmission is less of a risk. A former preschool director who trained other teachers in San Diego, Withrow weaves nature into her curriculum and recruited her husband, a hot air balloon pilot, to give lessons on weather and wind.

The parents that seek out her program, she said, share a lot of the concerns she had last year when she decided to homeschool her kindergartner.

“I just felt in my heart that classrooms right now aren’t education- and student-centered,” she said. “I think they’re centered on the virus.”

Far from Southern California, on a five-acre farm outside St. Paul, Minnesota, Diane Smith formed a pod with two other families from the White Bear Lake Area Schools. A former fifth-grade teacher in a Catholic school, Smith teaches the students biology and they pooled their money to hire an Algebra II teacher. They’ve taken boat tours on the St. Croix River to study the region’s many bodies of water, and one student’s father, a medical researcher, helped the group dissect a pig’s heart for a science lesson.

But this fall, the parents realized that their children — mostly in high school — need more academic instruction than they can provide. The students are taking some classes from a large homeschool co-op. Smith said the parents have been “blown away” by the support they’ve received from the homeschool community. “Clearly, there is a movement,” she said. “You really aren’t alone.”

Opposition to the district’s mask mandate and restrictions such as keeping students in cohorts to eat lunch are among parents’ reasons for leaving the district. A February lesson focusing on privilege and racial oppression also played a role. Sixth graders in a choir class were asked to consider how it would feel to be in a privileged group, which included being white, male, Christian or heterosexual, or in a targeted group, including being a person of color, female, Muslim, or LGBT. Smith said, “I thought, ‘Is this the direction we’re going?’”

‘A total place of liberation’

Perhaps one sign of pods’ staying power is that they’ve appealed to parents on all sides of the nation’s frequently polarized debates over race and discrimination in schools. Torlecia Bates decided to pull 10-year-old Kaden and 8-year-old Kaylee out of the Louisa County Public Schools, near Richmond, Virginia, last year when her worries over schools’ COVID-19 mitigation procedures were replaced with concerns about the impact of racial unrest on her children.

“I had a reality check,” she said. “I thought, ‘I have these cute brown kids, but will the world see them as a threat?’”

She began homeschooling and meeting up with other former public school families for playdates. She tagged along on field trips with Cultural Roots Co-op, a homeschool group that serves Black and multiracial families. This year, she’s joined the group, where her children get help with math, visit museums, go kayaking and “get real-life coping skills,” she said. She teaches them on the other days, and then works the night shift at home for a banking company.

Initially unsure about her decision to leave the district, she said she “went from a place of extreme anxiety, and not being sure if I would be able to measure up, to a total place of liberation.”

She’s also saving money. Bates used to spend $13,000 a year on child care, plus the cost of afterschool programs and activities. Now, she’s spending $250 per month for two days a week at the co-op.

Cultural Roots is among the programs receiving support from the VELA Education Fund, which launched last year to support nontraditional options like microschools. Some programs use the funds to provide scholarships, and those leading larger pods and co-ops frequently offer sliding fee scales for families.

The microschool concept has caught the attention of choice-supporting policymakers, such as Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican. He announced last month that he’s allocating $3.5 million to the Black Mothers Forum, an advocacy organization, to launch microschools. And in Nevada, the city of North Las Vegas used federal relief funds and worked with a nonprofit to create the Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy, which targets city employees and other frontline personnel.

“It’s almost like free private school,” said Maria Austad, a senior office assistant in the city’s public works department. Last year, she pulled her daughter Isabella, who has Asperger’s syndrome, out of the Clark County School District, where she was frequently getting in disciplinary trouble because of problems with social interaction.

Austad enrolled her daughter in the academy, where students use an online curriculum with help from on-site teaching assistants.

Others found that their local schools were the most sensible choice. Amber Besson, a mother of three who lives north of Wichita, put her youngest in Green Gate for kindergarten last year, while her two other children, 12 and 14, stayed with the Valley Center district’s distance learning program. Now it’s just easier to have everyone together.

“Spending an hour or more in the car before and after work didn’t put me home at a time where I was able to make the best of our evenings with all of our kids,” she said.

To put the movement in perspective, those who have been able to make pods work represent less than 3 percent of the overall K-12 population. But “even a small shift in the enrollment behavior of families can have a big effect on K-12 systems, especially once federal pandemic recovery funding runs dry,” said Alex Spurrier, a senior analyst at Bellwether Education Partners. He wrote about pods and microschools in “The Overlooked,” a report released with the Walton Family Foundation in August. He counted those joining pods and microschools among the 8.7 million students who changed schools between 2019-20 and 2020-21 for reasons other than a normal promotion to the next grade.

Katie Saiz, who co-founded the Green Gate program with her husband in 2008, tells callers her program is full. For years, they only served preschoolers out of their home, but come fall 2020, “there was this huge need in the community,” she said, adding that 97 percent of the families that joined last year because of the pandemic are back this fall.

When the Monsours joined, their third grader was ahead in math, but struggling in language arts. Now, his mother said, he’s become a more confident reader.

“It’s really cool when you are able to put a kid where they need to be,” Saiz said, “and don’t worry so much about where they should be.”

Lead Image: Art teacher Khalid Thompson leads students from the Cultural Roots Co-op on a tour of the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. (Cultural Roots Co-op)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter