Former D.C. Schools Chief’s New Venture, Reconstruction, Celebrates the Black Experience While Staying ‘Out of the Fray’

By Linda Jacobson | October 4, 2021

Kendrah Foster had already planned a Mardi Gras-inspired “staycation” with her three children in July when she heard about a week-long virtual cooking class for Pittsburgh families that featured gumbo on the menu.

Donning child-sized toques — the tall, white, pleated hats worn by chefs — Winter, 9, DeVonte, 8, and Stormy, 7, took charge of the kitchen, perfecting their knife skills by slicing bell peppers and stirring the roux until it reached a golden brown.

By the end of the course, they’d made traditional Southern greens, black-eyed peas, smothered chicken and other dishes that trace back to African culture. “They’re already talking about making the cornbread for Thanksgiving,” said Foster.

The culinary-themed Black history lesson, called Soul Food Summer Camp, was a local twist on one of the popular courses available from Reconstruction — an online enrichment platform celebrating Black Americans’ contributions and heritage.

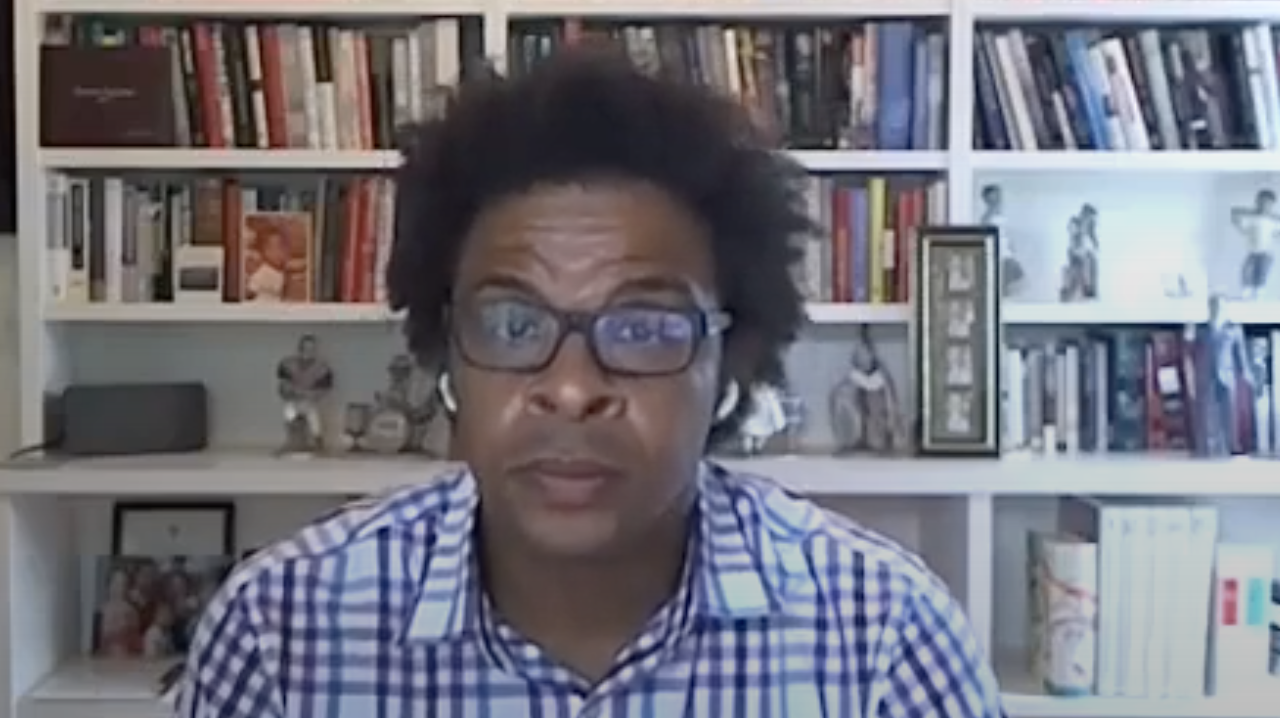

In a year when classroom discussions about race and discrimination have bitterly divided school boards and statehouses, topics such as the essential role of corn in the diet of Black slaves may seem conspicuously noncontroversial. But fostering Black children’s “positive identity development” in the way Hebrew and Chinese schools do for children in other communities is exactly what Kaya Henderson had in mind when she launched Reconstruction a year ago. As former chancellor of the District of Columbia Public Schools, she wants to counter a narrative that Black families don’t value education.

Roughly 15,000 students are expected to sign up this fall for Reconstruction, a for-profit company that delivers live enrichment classes on Black history and culture over Zoom to students across the country. Black parents browsing its offerings find courses “unapologetically” designed for them and their children. “Shorties” (4- to 11-year-olds), “Youngins” (12- to 14-year-olds) and “Gen Z” youth cover Black entrepreneurship and cultural knowledge. Students can design apps for nonprofits working to support the Black community or study speeches and sermons of famous Black orators. Parents began asking for their own courses, so there’s a Read and Rap Book Club for “grown folks.”

Henderson’s decision to market directly to families and nonprofit organizations has allowed Reconstruction to bypass school district politics.

“I didn’t want to be at the whim of state legislators,” said Henderson, who credits the program’s more celebratory approach to Black history for keeping it under the radar. “We’re not out here talking about white people being awful. We’re giving young people positive examples, and that keeps us a little bit out of the fray.”

But that doesn’t mean the curriculum ignores America’s painful racial history. For example, several courses include lessons on the once-thriving commercial district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as Black Wall Street, and the 1921 massacre in which a white mob attacked residents, homes and businesses there.

‘A place of belonging’

The mission to give students a more comprehensive story begins with the program’s name: Reconstruction, the period following the Civil War when Confederate states rejoined the Union and former slaves got their first taste of freedom. It’s “a lesser known part of American history when African Americans were thriving politically, economically, educationally,” Henderson said. “We wanted to challenge folks who don’t know that part of our history to explore it. And we wanted to remind our students that they come from a rich tradition of Black excellence in America that they have a responsibility to uphold.”

A former Teach for America executive director in D.C., Henderson served under former Chancellor Michelle Rhee, who was controversial for closing low-performing schools and instituting a tough teacher evaluation system. With mayoral control of schools, Henderson continued those reforms during her tenure, which ended in 2016. While enrollment grew and test scores increased under her leadership, some critics argued her strategies didn’t do enough to close racial achievement gaps. And after she resigned, the city’s Board of Ethics and Government Accountability reprimanded her for granting the requests of colleagues to place their children in preferred schools rather than submitting them to the district’s competitive lottery system.

When it came to designing Reconstruction, her experience helming the 51,000 student district was instructional. It helped fuel a desire to sidestep a K-12 bureaucracy that hasn’t always done right by African-Americans.

Black students, she said, often have negative experiences in school, and Henderson wanted Reconstruction to be “a place of belonging, joy and love.” She also didn’t want to conform to 50 different sets of state standards — particularly in light of new bans on lessons or materials that could make students feel uncomfortable or guilty because of their race or gender. Reconstruction launched about five months before states began considering legislation to outlaw so-called critical race theory — a loose umbrella of topics from Black history to culturally responsive teaching.

Reconstruction courses have no more than 10 students, and there aren’t any end-of-course tests. That doesn’t mean the lessons go easy on academics, Henderson said. The reading and math courses can add up to a full year’s curriculum.

“To me, the rigor is paramount, but I’m not trying to replace school,” said Henderson.

Reconstruction’s business model also gives Henderson control over who she hires as “reconstructors”— the team of young educators who teach the courses.

“There have been enough hot mic episodes over the years to show that everyone who’s teaching children doesn’t always believe in Black children,” Henderson said.

In March, for instance, a California teacher resigned after making comments on a Zoom call about Black parents teaching their children to make excuses for their behavior. A mother recorded the teacher, who was apparently unaware the call was ongoing.

Henderson and co-founder Roland Fryer, a Harvard economics professor, initially discussed whether Reconstruction should be a school curriculum or offered outside the traditional system. Fryer, Henderson said, leaned toward integrating the concept into schools.

“I don’t want [children] to be taught that there’s slavery, Jim Crow and then you. I want for the history to be full and for them to be empowered,” Fryer said during a recent two-part interview on the Invisible Men podcast, co-hosted by Ian Rowe, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

Those episodes aired the same week that Fryer resumed teaching at Harvard after completing a two-year probation and training on “appropriate boundaries.” In 2019, the university placed him on administrative leave after an investigation showed he had violated sexual harassment policies and engaged in “unwelcome” conduct, such as talking about sex and telling sexual jokes in the Education Innovation Lab he ran. He denied accusations of harassment and retaliation, but later apologized in an op-ed about making “off-color jokes” and commenting on colleagues’ dating lives.An investigation into whether Fryer retaliated against an accuser closed when a female employee withdrew her complaint.

The university shut down the lab, where Fryer — who, at 30, became the youngest Black professor to earn tenure at Harvard — led notable research on the effectiveness of charter schools and racial disparities in education and policing.

As he faced disciplinary action at Harvard, Fryer co-founded Equal Opportunity Ventures in 2019 to support Reconstruction and other startups that focus on closing racial disparities and expanding economic opportunity. He serves as chair of Reconstruction’s board of directors, but Henderson said he is not involved in daily operations. She added that she’s never received any questions or concerns from parents or organizations about his involvement.

In an email to The 74, Fryer declined to comment on the probation or his work developing Reconstruction during that time. But he said, “I am delighted to be back teaching at Harvard, and currently have a class of nearly 200 students eager to learn about how companies like Reconstruction can both change the world around us and be a sustainable business.”

‘Culturally relevant perspectives’

That business model is primarily aimed at parents, who pay $100 for each 10-session course. But nonprofits, such as the Grable Foundation in Pittsburgh, are making the program available to students for free.

The traditional education system has also taken notice.

In the Baltimore City Public Schools last year, 140 students from 17 schools took an afterschool program featuring Reconstruction’s course on the movement of Africans into the Americas and the Caribbean during the slave trade.

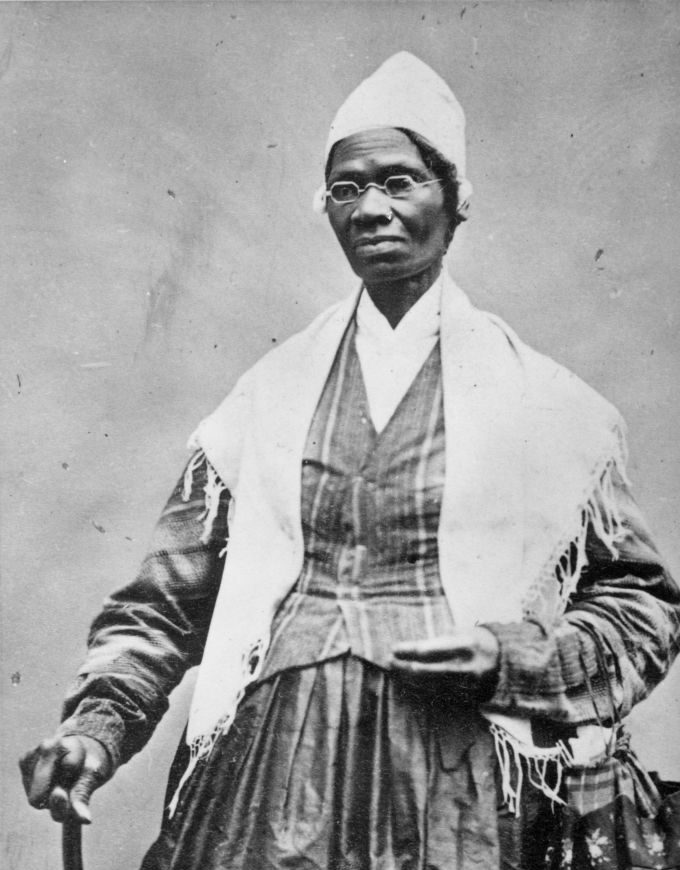

David Anderson, a junior in an advanced STEM program at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, said he learned about Manhattan’s Seneca Village, a pre-Civil War African American settlement that got pushed out to develop Central Park. The life of abolitionist Sojourner Truth also stuck with him.

“She was more under the radar than Harriet Tubman, but her job was just as important,” Anderson said.

David’s mother, Annette Campbell Anderson, an educator and professor at Johns Hopkins University, was initially skeptical about the program, having been underwhelmed by the district’s previous afterschool offerings. But she was impressed by her son’s commitment to the course.

“I found myself needing to change our family dinner schedule on Tuesdays when he had class because he refused to leave the sessions early,” she said. “And if I served dinner early, he raced upstairs to be on time — for a Zoom session.”

Reconstruction has won praise from those on opposite sides of the debate over critical race theory.

Sharif El-Mekki, CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, said it’s important for Black children to have a space designed for them, even if it’s virtual.

“Out-of-school-time has always been one of the most-effective and least invested-in levers for achievement for Black children,” said El-Mekki, whose daughters, Zaynab and Zakiyyah, participated in Reconstruction’s pilot and then took the cooking class.

The program provides Black children with a “holistic, centering and respectful curriculum,” he said, adding that students who participate in the program could become “powerful advocates” for more culturally responsive teaching in their own schools.

Like other Black educators, El-Mekki has said the debates over critical race theory misrepresent what schools actually teach students but also ignore the persistent educational inequalities affecting Black and Hispanic students.

At a time when some states, such as California, Connecticut and Virginia, are expanding ethnic studies in the curriculum, he thinks Reconstruction is one way to re-engage Black students and others “that have been perpetually let down by the educational ecosystem.”

‘All kids of all races’

At the National Charter School Conference in June, El-Mekki and Rowe, from the American Enterprise Institute, strongly disagreed about the furor over critical race theory, but joined in their praise for Henderson’s program.

In a “shout-out” for Reconstruction, Rowe said: “I think it’s good that we’re having more discussions about what should be the complete [story] — warts and all, oppression and resilience — that we’re teaching all kids of all races about what has transpired with African Americans in the United States.”

The process isn’t always easy. White parents are among Reconstruction’s customers, Henderson said, but some have requested that their child not be the only non-Black student in a class. Others have even asked for all-white classes, a request that would have raised the spectre of segregation in the public school world she left behind.

Those requests don’t bother her.

Though there hasn’t yet been enough demand for an all-white class, Henderson said she’d “absolutely consider it.” Some parents tell her their kids don’t have a lot of experience interacting with Black children and worry they might say the wrong thing. The goal, she said, is to get the message out to as wide an audience as possible.

“This stuff is hard and we’re all going to make mistakes,” she said. “We are designed for and by African Americans, but we need everyone to learn this history.”

Lead Image: Winter Herbert (L-R), Stormy Foster and DeVonte Foster prepare a meal as part of Soul Food Summer Camp, a week-long virtual cooking course for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, students participating in Reconstruction. (Catapult Greater Pittsburgh)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter