Exclusive: Police Cam Videos Reveal How School Cops and Educators Restrain Kids in Crisis

By Mark Keierleber | March 3, 2022

Sydney is having a mental breakdown in a special education classroom when the 9-year-old girl tries — but fails — to pelt a police officer with a cracker.

“Not very good aim,” responds Randy Boyden, a school resource officer with the police department in South St. Paul, Minnesota, called in for backup that day by school staff.

“What are you going to do?” the brash fourth-grader spits back before taking another shot.

Sydney, a victim of child abuse and neglect whose real name The 74 is shielding, suffers from multiple disorders and, as a result, struggles to regulate her behavior and emotions. She fell into an hours-long fit of rage that day after not wanting to go to Spanish class, including wielding a pair of scissors, throwing a chair against a classroom window and biting and kicking her teacher. She landed blows on several of the adults in the room and by the time the cops arrived, school staff had already restrained Sydney in an effort to de-escalate the situation.

“If you get it into my mouth, I’ll eat it,” Boyden tells the overwrought girl in an exchange that student disabilities experts saw as taunting and one called “really disturbing.”

Sydney throws two more crackers before she climbs onto a high cabinet, rips a speaker off the wall and flings it to the ground. At this moment, it seems most likely the student could hurt herself, yet it isn’t until she scampers down and jabs a SMART Board with a marker that the adults move in.

Special education teacher Tony Phillips and school Principal Terry Bretoi grab her by the elbows, force her to walk in circles and then lower her to the ground. As they press down on her arms and shoulders, Boyden and another police officer, Mellissa Cavalier, join in. The officers hold Sydney to the carpet by her kneecaps as she tries to break free, squirming and whimpering in distress. Eventually, she lets go of the marker, stops resisting and her 75-pound body goes limp.

The final physical struggle inside her elementary school involving the police lasts for nearly six, difficult-to-watch minutes. Students like Sydney, Black and in special education, are among the most likely in the U.S. to be physically restrained in school. Except for the occasional cell phone video, however, the highly controversial tactic is rarely witnessed by outsiders. In Sydney’s case, the video documentation recorded on police body cameras is even more remarkable because it captures the second time in little more than a week that educators and those same two officers physically restrained the disabled girl during a mental health crisis.

Just eight days earlier, after she ran out of school, six adults dragged her by the limbs and forced her into the back of a police car where they locked her inside as she put words to her misery.

“I hate school, I hate work and I want to die,” she says. “That’s what’s wrong.”

This story is based on records provided exclusively to The 74 by Sydney’s adoptive parents, including the police body-cam footage, audio recordings, police reports, special education reports, disciplinary records and other documents. The videos, after being edited to obscure Sydney’s identity, were shared with experts who commented for this story. The 74 sought out the officers and school staff in the videos, some of whom have since changed jobs or plan to soon. They either did not respond or declined to be interviewed.

After watching videos from both incidents, special education attorney Wendy Tucker said they reaffirmed The Center for Learner Equity’s opposition to police presence in schools, particularly when it comes to their interactions with children who are disabled. When George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in nearby Minneapolis, it generated a national conversation about police use of force. Dozens of districts nationwide cut ties with the police, who disproportionately arrest children with disabilities.

“This video demonstrates front and center the problem of mixing kids with disabilities and police officers,” said Tucker, the national nonprofit’s senior policy director. “This girl is the poster child for removing law enforcement from schools.”

Imminent danger vs. property damage

For Sydney’s adoptive parents, whose real names were also changed to protect their daughter, the video footage from the two incidents in the winter of 2019 spurred a years-long campaign to hold officials accountable for the girl’s cuts, bruises and mental scars. In response, the Minnesota Department of Education found that school staff violated state law, but officers never faced similar sanctions. In late February, the education department sent a letter notifying Sydney’s parents that they would investigate an allegation that she “may have been mentally injured” by school staff.

Robert, the girl’s father, said that educators and police had only intensified his daughter’s struggles — a reality he said reflects America’s bleak mental health system. Rather than understanding the girl’s disabilities and calming the situation, he charged, they responded with excessive force and a desire to take control. It remains unclear the degree to which the two school resource officers were trained in how to de-escalate situations involving children with disabilities.

“Police aren’t designed to respond to this type of thing, it’s not their job,” Robert said. “Their job is to find the killer, it’s to stop the speeding car that robbed a bank. It’s not necessarily to respond to the school for a 9-year-old that’s having a mental health crisis.”

Educators and police were clearly placed in a volatile situation with Sydney. Federal law requires school officials to accommodate Sydney and other children with special needs, but some educators have acknowledged they struggle to support students with the most significant behavioral health issues. Sydney’s case highlights those complexities and the challenges educators face when thrust into these highly fraught interactions.

Sheldon Greenberg, a former police officer and education professor at Johns Hopkins University, offered a different assessment of how the police interacted with Sydney. Good officers have “an incredible sixth sense about people’s behavior” and follow a “use-of-force spectrum” that begins with verbal persuasion and moves up to physical confrontation. Officers can generally de-escalate situations without physical force, Greenberg said, and in responding to Sydney, the officers “followed the spectrum beautifully.”

“They were patient, there was gentle talk in the beginning,” he said. Ultimately, he said that officers must assess crisis situations and prevent them from escalating.

Sydney, already debilitated by childhood trauma, said she tries hard to forget about the times school staff and campus cops grabbed her arms and legs and held her down — at times in violation of state education law.

“I just feel comforted knowing that I’m out of that school,” said Sydney, who switched elementary schools just weeks after the incidents and is now in middle school. She reflected on the source of her outbursts, which have grown less frequent. “I feel unloved and stuff, and a lot of sad and dark feelings.”

Thousands of students in Minnesota and across the country are physically restrained at school each year despite efforts to curtail a practice that’s led to injuries and, in rare cases, death. In Minnesota, state law only allows educators to restrain disabled children in emergency situations where someone is in imminent danger of physical harm. Experts questioned whether Sydney’s behavior had reached that threshold and said that school officials appeared more concerned with preventing property damage.

During the part of the incident inside the special education classroom captured on video, officials didn’t use physical force until she stabbed at the costly SMART Board. The state banned student restraints to prevent property damage in 2013.

Robert believes that physical restraints are necessary when children present imminent danger to themselves or others. But in their interactions with Sydney, he believes the adults responded excessively. Rather than protecting Sydney, the police and school staff assaulted her, Robert alleged, and falsely imprisoned her when they secluded her in the back of the squad car.

“It wasn’t just the police trying to force her into the back of a police car,” Robert said, adding that school staff were similarly at fault. “Why, in this case, are they saying to the school employees, ‘Yeah, let’s force her into the back of the car — you can help.’”

The South St. Paul Public Schools acknowledged that they changed their practices after the state Education Department found they violated the law in restraining Sydney. The district said student privacy rules prohibited them from discussing the case further. The South St. Paul Police Department cleared the officers of any wrongdoing, the police chief said.

‘Such an extreme’

Both of the officers had interacted with Sydney before and knew at least some of her history. One of them, Cavalier, was there on one of the worst days: When the little girl was placed into foster care. Yet in the footage, she dismisses the girl’s distress as a desire to stay home and watch movies.

“That’s the whole thing,” Cavalier says while Sydney is locked in the car, “she doesn’t want to be in school today.”

Sydney was born with fetal alcohol syndrome to a mother whose losing battle with addiction had forced the family into homelessness. A victim of physical abuse and neglect, she was placed with her adoptive family after school staff watched her biological mother hit Sydney with a belt during a February 2017 meeting on campus, according to police records. Though school officials called police — including Cavalier — to the scene, Robert said their failure to immediately intervene shattered his adopted daughter’s trust in them.

“Nobody in the room made attempts to stop that from happening,” he said. “The principal was there and didn’t stop it immediately.”

On the same day Sydney was beaten by her mother and humiliated at school, Robert and Julia, who had begun the process to become foster parents, got the call: Sydney was in need of emergency placement. The couple scrambled to open their home as refuge to a child they knew little about. They fed her McDonald’s, collected her belongings — a teddy bear, hair brushes and clothes that had grown too tight — in a small pink bin and introduced her to their dogs Lucy, Finley and Lola. Lucy, a Pomeranian seemingly aware of the girl’s recurring nightmares, slept in Sydney’s bedroom every night for a year.

By that time, Sydney, then 6, already had a history of school suspensions for aggressive behavior. First-time parents, Robert and Julia learned almost immediately that Sydney was struggling to identify and control her emotions.

“Her body doesn’t know what the emotion she’s feeling is,” Robert said. “If you’re having this emotion and you don’t know what it is, she would tend to panic and freak out. Instead of going, ‘I feel sad, I feel happy,’ she didn’t know what those emotions actually were.”

In addition to fetal alcohol syndrome, Sydney was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, ADHD and reactive attachment disorder, a serious condition that results when children’s basic needs for comfort, affection and care are not met. She was placed in special education, but Sydney’s parents said that school staff failed to fully comprehend the root causes of her outbursts, and instead wrote them off as willful misbehavior. The symptoms of trauma can mimic misbehavior, and Tucker, of The Center for Learner Equity, said it’s critical for educators to recognize that such actions are a form of communication.

“When they’re communicating that they’re struggling or they’re having a hard time, the worst thing that you can do is exacerbate that by physically holding them down and taking more control from them,” she said.

Sydney, who attends myriad therapies, said she’s “just matured a little bit” since the incidents in the video. Her parents say she’s made significant progress and they are not aware of any restraints in school since then. To her, there was no confusion about the source of her meltdowns.

“I guess some trauma,” the self-aware 11-year-old said in an interview, adding that her biological mother was frequently absent and in jail. “So I guess, kind of neglect.”

Once in her new home, Sydney’s outbursts continued and Robert and Julia were getting beaten up as they tried to calm her, including the time Julia had to get stitches after getting hit in the lip. Such scenes may have deterred others, but for the couple, who would adopt Sydney in 2018, the bond had already been forged.

“We fell in love with her the first week she was here,” Robert said. “It was ‘This kid is so cool, I love this kid.’ Part of me didn’t want her to ever leave.”

Still, her behaviors were a force to be reckoned with, so they signed up for a training program on crisis prevention, which included instruction on de-escalation and how to use physical restraints. Parents don’t generally enroll in the program, which is designed for special education teachers and emergency responders. The course, Robert said, was “one of the best things that we have done.”

Ironically, at the same time the couple was attending a December 2019 training session, school staff called to report that Sydney was in crisis. Once they obtained the police body-cam footage of her getting pinned to the floor in the special education classroom, Robert and Julia said it was their training that allowed them to conclude that the restraints placed on their daughter differed drastically from what they had been taught.

‘Nowhere in [the training course] does it say ‘hold down their kneecaps and their elbows and their wrists, and twist them up,’” Julia said. “You have four adults on her already. Why do they go to such an extreme?”

‘Do we need to handcuff you?’

On the day she would find herself locked in a cop car, Sydney had been struggling in math class, so she fled. Overwhelmed, she bolted from school and stood in a nearby street, where she attempted to get struck by oncoming traffic.

Yet officials don’t use force until she throws what her suspension report describes as “landscaping blocks.” One block comes close to striking Phillips, the special education teacher. Another clobbers a parked pickup truck.

That’s when officer Cavalier gives Sydney an ultimatum — go back to school or wait in the back of her squad car — before tugging on the girl by her arm.

“We can’t damage people’s property and we can’t hurt anybody,” Cavalier says before the girl tries to kick free and drops to her knees in the middle of the street. Together, Cavalier, Boyden and four school employees grab her arms and legs and force her into the car, where she puts up a fight. As she tries to escape from the back seat, Sydney at one point reaches for Boyden’s gun.

“Do we need to handcuff you?” Cavalier asks Sydney in response. “I don’t want to do that but you can’t just start grabbing things that don’t belong to you.”

Greenberg, the Johns Hopkins professor, said the public generally sees police use-of-force during extreme, worst-case scenarios. Though he said the video footage involving Sydney provides a limited window into those incidents, he felt the officers “showed incredible restraint before applying restraint.”

“You can tell when someone is reaching a point that harm to self or harm to others is about to occur,” he said. “You just know it, you feel it and you know you have to do something to minimize that harm.”

Police officers who are stationed inside schools full time generally are given much greater discretion than educators in how they respond to disruptive students. Just last year, efforts in Minnesota to adopt modest regulations to officers’ restraint practices in schools fell short. State legislation would have prohibited cops from placing students in the face-down “prone restraint,” — like the one used on George Floyd — and would have required them to receive the same training as school staff. The state education department, which endorsed the reforms, will continue to promote the changes, assistant commissioner Daron Korte, who oversees student support services, told The 74.

“We just wanted to make sure that there’s at least a minimum level of training,” that officers know how to use safe restraint techniques and understand “that this should be used in a last-ditch emergency situation,” he said.

While some advocates oppose all forms of student restraints, Robert and Julia believe that physical holds are necessary in some emergency situations if done properly. When Sydney was in the street, for example, school staff could have used a brief hold to move her to the grass. They also could have moved her to a room in the school with a padded floor and a mini-trampoline. Instead, they dragged her by the limbs and locked her in the back of the police car.

“Why would you let a child who says ‘I’m going to kill myself’ and ‘I’m going to go sit in that street and I’m going to get hit by a car,’ why wouldn’t you restrain them at that point so they don’t commit suicide?” Julia asked. “We’re not necessarily against restraint, but you have to have trusted people who are well trained, who are doing it with dignity and have the right intentions.”

Similar situations have come up in the past. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union sued a Kentucky sheriff’s deputy for handcuffing two elementary school students above the elbow who were acting out as a result of their disabilities. One incident was captured in a viral cell phone video. That case ended with a $337,000 settlement. In 2020, the city of Flint, Michigan, paid $40,000 to settle a lawsuit accusing an officer of excessive force when he handcuffed a disabled 7-year-old boy for roughly an hour after he ran around on school bleachers and kicked a supply cart during an afterschool program.

In Sydney’s case, West Resendes, a legal fellow with the ACLU’s disability rights program, said school staff used improper restraint techniques in both incidents to control the girl’s disability-related behaviors and shouldn’t have called the police for help. In their interactions with Sydney, he said that officials treated her “not as a human being but as an object” and were unclear about why she was being restrained.

“Seeing the male officer egg her on about not having good aim or wasting crackers was really disturbing — and it predictably and directly led to an escalation of the situation,” Resendes said.

‘Make sure that this doesn’t happen again’

Sydney is Black and her adoptive parents are white — a reality the couple said gave them a new perspective on the police and racial bias. On multiple occasions, her outbursts have prompted aggressive police responses.

During one episode at the Mall of America, officers accused Robert of trying to abduct his daughter, he said. On another occasion, Robert had a gun pulled on him by a cop who mistook an exchange in the family car between him and a distraught Sydney as an assault.

Though officers backed off once they understood the context, Robert thought the cop might shoot him. In 2016, that same officer was involved in the fatal shooting of a man in crisis outside a McDonald’s restaurant. He was shot 15 times.

Sydney’s parents and special education advocates said that race was a likely factor in how educators and police responded and believe she may have been treated differently if she were white.

Dave Webb, the district superintendent, declined to be interviewed but said in an email that the district does not use physical restraints to discipline students. He acknowledged they had to update their restraint procedures to match state law after the two incidents with Sydney but said they had not been held liable for using the tactic in a way that is racially discriminatory.

“The district takes its obligation to comply with the laws governing restrictive procedures very seriously and provides ongoing training to its staff to comply with those legal requirements,” Webb said.

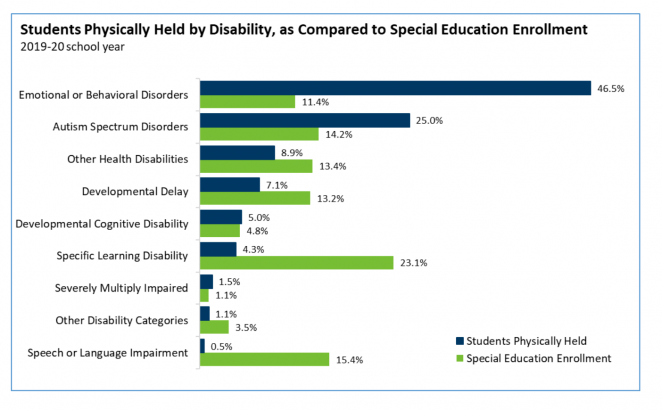

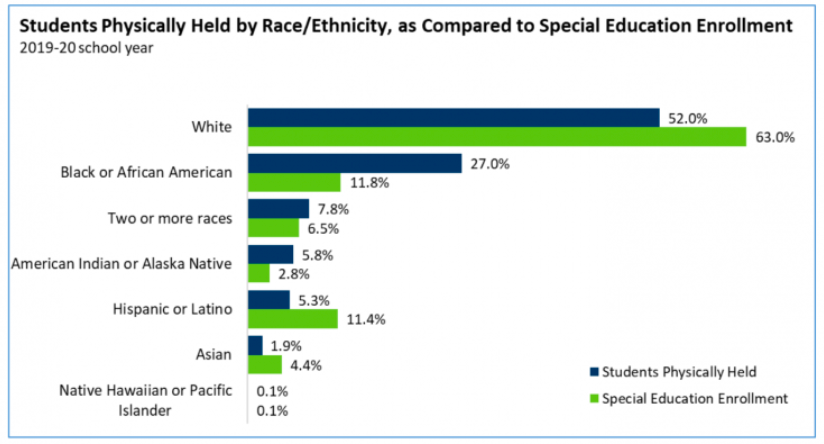

Years of federal education data have found that students of color — especially those with disabilities — are disproportionately restrained in schools. In Minnesota, Black students were 11.8 percent of students in special education during the 2019-20 school year but were subjected to 27 percent of the physical holds documented in schools, according to state data.

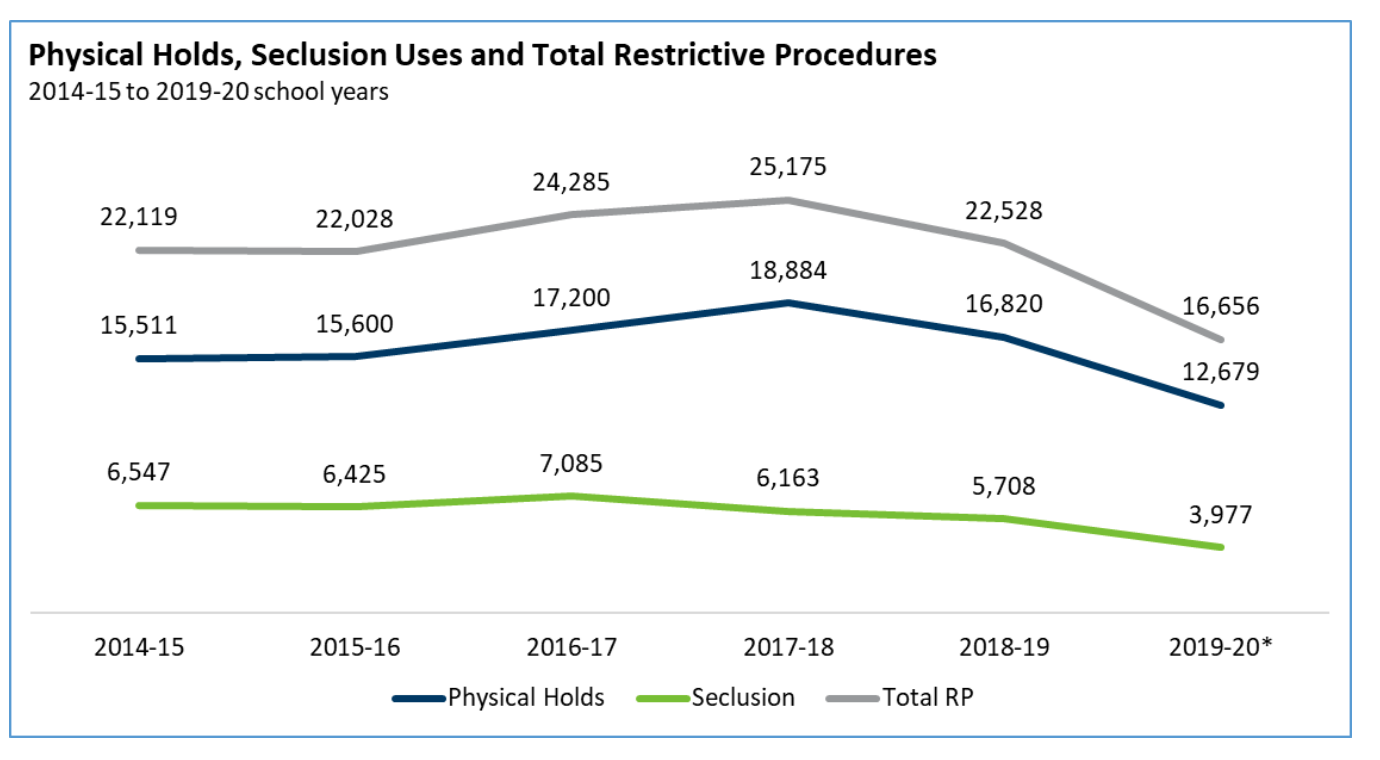

That school year, the latest for which state data is available, student restraints dropped by 25 percent, a change officials attributed to the pandemic as students learned from home during the second half of the year.

Initially, educators’ responses “looked textbook” when they talked calmly and tried to comfort Sydney, said Joshua Ladd, a staff attorney at the Minnesota Disability Law Center, but he faulted school staff for allowing police officers to take the lead in both situations as if they “had given up and just decided to start watching.” Ladd said that school staff were clearly unable to support Sydney’s needs and that her behaviors — such as bolting from class — were a form of communication.

“I would describe her communication as saying ‘I’m not safe here and I can’t trust adults because adults have let me down my entire life,’” he said. “‘I have learned to protect myself and take care of myself because the adults around me have failed me.’”

After acquiring the body-cam footage, Sydney’s parents filed a formal complaint and a state education department investigation found that school staff broke the law when they restrained the girl in “non-emergency” situations, among other violations. The officers never faced any repercussions. Both incidents were investigated but no disciplinary action was taken against the two school resource officers, South St. Paul Police Chief William Messerich wrote in an email. He declined to comment further.

District officials were required to undergo training and update school policy to make clear that staff could not restrain kids to “prevent serious property damage” consistent with state law. They also required school staff to reassess Sydney’s special education services.

“It already happened, there’s nothing you can do to go back in time to stop that from happening,” Korte, the assistant commissioner, said of the incidents. But moving forward, district staff were required to develop a strategy “to make sure that this didn’t happen again.”

Sydney’s parents were left longing for more. The interventions did little to help their daughter’s suffering, they said, or to hold officials accountable for pinning her to the ground. Robert, a mechanic, and Julia, a teacher, considered suing the district and the police, but were discouraged by the cost of hiring an attorney.

A student maltreatment investigation could result in educators losing their licenses. Robert said he filed multiple complaints against the educators who restrained Sydney but the state initially declined to open an inquiry. He said that changed just weeks ago after Sydney’s therapy team submitted a report stating that she suffered trauma directly related to the restraints at school.

The investigation raises the possibility that Sydney’s parents may get confirmation of something they’ve long maintained — that their daughter was abused in a manner that went beyond poor training or outdated policy.

They realize other parents of disabled children never get near that level of resolution — and believe they may not have either without video evidence.

“How many kids, how many nonverbal kids, does it happen to?” Robert asked. “Kids that can’t go home and tell their parents ‘Yeah, there were four adults pinning me to the ground today.’ They just come home and destroy the house and the parents are left wondering what is going on.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter