Police-Free Schools? This Suburban Minneapolis District Expelled Its Cops Years Ago

By Mark Keierleber | July 8, 2020

After George Floyd’s death galvanized one of the largest protest movements in U.S. history, schools nationwide began to sever ties with police departments. Intermediate District 287 replaced cops with “safety coaches” in 2017 — offering insight into the promise and limitations of such a move.

Samuel White woke to a gun pointed at his head.

It was 1987, and his grandfather had just purchased a new car. When someone reported the vehicle stolen, police raided his family’s Minneapolis home and ordered the Black high school student to get down on the floor.

The near-fatal mistake wasn’t White’s last negative encounter with the city’s embattled police department. But the experience and others like it helped inform his role at Intermediate District 287 in suburban Minneapolis, where he now helps maintain order as a “student safety coach.”

White isn’t a cop — though he was happy to replace one. Beginning in 2017, years ahead of the national curve, the district ended its contracts with three local police departments and removed school-based officers from its campuses. The safety coaches who replaced them employ an approach centered on addressing students’ mental health needs and de-escalating conflict.

During incidents “where an officer would go to an extreme, we don’t have to go to that extreme,” White said, adding that calling police is now a last resort. “A lot of time, we’ll even call home and try to get a kid to talk to [a] parent or somebody from home before we even have to go to that.”

The idea of removing police from schools is getting a fresh look amid the tumult following the death of George Floyd, a Black man from Minneapolis, in police custody in May. Now, as districts from Portland to Milwaukee sever ties with police departments, District 287 offers insight into the promise — and limitations — of such a move.

For White and his fellow coaches, the need to shake up the status quo was clear. Prior to 2017, police frequently used force against students — Black youth in particular. Officers tased and body-slammed students, they said, but their crackdown on misbehavior largely failed to make campuses safer. These negative interactions, paired with a desire to save money, prompted officials to adopt a different approach.

To exemplify the safety coaches’ success, Superintendent Sandy Lewandowski cites a sharp drop in student arrests, from 65 to 12 in the program’s first year, according to district data. The majority of arrests under the policing model were for low-level offenses like disrupting class. Coaches still call police when violent outbursts spin out of control, but only in 2 percent of their interactions with students, according to district data. In most cases, Lewandowski said, coaches are able to calm tensions.

The coaches, many of whom have years of experience working with special needs students in the district as paraprofessionals, spend their day bouncing between classrooms, interacting with students and responding to trouble. Rather than arresting students for misbehavior, the coaches use “restorative justice,” which relies on mediation to help students express their emotions in a more positive manner.

But in critical ways the atmosphere remains threatening for many. Since officers left campus, only 59 percent of district staff report feeling safe at school, according to a recent educator survey. Just 54 percent said they feel “at least as safe” as they did before the district launched the coach program — and roughly a third reported feeling less safe. In a district where violent outbursts are common, officials acknowledged that educator injuries, including concussions, arising from altercations with students remain a problem. In fact, workers’ compensation claims spiked after coaches replaced officers.

In a sign of a subtler culture shift, more than two-thirds of survey respondents said the coaches help students develop positive behaviors and deescalate tense situations, with one educator noting they help children express their feelings when they’re struggling in class.

‘Cuffed and stuffed’

At District 287, removing officers is part of a larger push to become a “trauma-sensitive organization.” The district, a cooperative of 11 school systems in the region, serves some of the region’s most at-risk kids, including those entangled in the juvenile justice system. They’re the victims — and perpetrators — of violence. They’ve experienced homelessness and mental illness. They’ve attacked teachers and threatened to take their own lives. While a majority of children are in special education, the district also offers programs for students at risk of dropping out.

“These kids come to us with a lot of trauma, a lot of mental health issues, a lot of challenges in their communities,” Lewandowski said. “We didn’t think those particular student characteristics were something that should be criminalized.”

But the impetus for the change had as much to do with the district’s bottom line as its nobler aspirations. New Hope Police Chief Tim Fournier, whose agency previously provided police to District 287, demanded a larger police presence to handle pervasive student misbehavior. In a memo to the city council in 2013, Fournier said an “unanticipated rise in violence” at one campus left the lone school-based officer “outnumbered and without backup,” at one point tasing a student in self-defense. If the district didn’t agree to pay more than $60,000 for a second officer, he warned, the department could stop providing it with school-based police altogether.

“Kids were tased, kids were cuffed and stuffed, kids were manhandled. Do you know how tough it is for me to watch a kid handcuffed to a bench in a police officer’s office in school? It’s awful. It’s the worst feeling ever.” —Don West, safety coach at Intermediate District 287

Officials at the department, and two other police agencies that previously provided officers to the district, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The cost of providing backup for officers “gave us pause,” Lewandowski said. The district decided to take a hard look at campus police and the role they played in schools. She said the predominantly white police force tended to treat Black students more harshly than their white peers — suggesting they acted with implicit racial bias.

In interviews, school staff described the issue as pervasive. Officers were more lenient with white students, whose behavior they were more likely to chalk up to mental health issues. But Black students were treated as criminals.

Though students of color make up roughly half the district population, most of the campus-based police were white men. Some were able to build positive relationships with students, but that was far from the norm, safety coach Don West said. Instead, the officers largely kept to themselves and “came with force” when called to break up fights.

“Kids were tased, kids were cuffed and stuffed, kids were manhandled,” West said. “Do you know how tough it is for me to watch a kid handcuffed to a bench in a police officer’s office in school? It’s awful. It’s the worst feeling ever.”

Theon Jarrett, one of the district’s first safety coaches and now the group’s manager, said he soured on the idea of school policing when he saw officers point tasers at kids.

“The police in the school, they’re laughing, they think it’s funny,” Jarrett said. Officers were “continually retraumatizing already-traumatized” students, he said, and “laughing like it’s a joke.”

“So I am a big advocate of not having police in our schools,” he said. “In any school.”

A softer approach

To reach 287’s student body, the district hired a diverse group of coaches who were no strangers to racism and negative interactions with police.

Before pursuing a career in education, safety coach Marcu Whitlock got a college degree in criminal justice. As a Minneapolis teen in the 1990s, he didn’t think fondly of cops because “my friends and I were constantly being harassed walking to and from the corner store.”

He once hoped that becoming a police officer would allow him to be a “change agent.” But as a safety coach, he said, he has found something better: an approach to addressing misbehavior that doesn’t rely on force.

As a coach, “you have to be a master of conversation, of tactful communication,” he said, noting that police officers at the district didn’t always have time “to be the social worker, to be the big brother, the guiding light, the mentor.”

Safety coaches are afforded the time to “get to know each and every student,” said Jayne Tiedemann, principal at South Education Center, one of the campuses in the district.

“Our students really need that culture of safety and security and relationships and trust,” Tiedemann said. “They come to school to learn, and if they are worried about a uniform with a gun, they’re never going to be able to concentrate.”

A growing body of research suggests that traumatic experiences impede students’ learning and their ability to manage emotions. Yet there’s little guidance on how to best deploy “school-based behavior responders” such as safety coaches because “the move away from police officers in school and toward other means of behavior intervention is relatively new,” according to a draft report on District 287’s reforms from the nonprofit Wilder Foundation.

The power of relationships

For West, the safety coach, the key to reaching the district’s vulnerable students is through personal connections.

A recovering alcoholic who grew up in the projects in California, he witnessed the turmoil that followed Rodney King’s violent beating at the hands of Los Angeles police in 1991. He’s been racially profiled by police on numerous occasions.

Whereas school-based officers frequently arrested students for minor infractions under the previous model, now “those little fires get extinguished immediately” because young people listen to authority figures they trust.

“For them to be able to talk to you is a big difference — it’s not always us talking to them,” he said. “Listening to what they need is a big difference.”

Once that rapport is established, he said, the students long for the positive interactions. He pointed as an example to the campus closures sparked by the coronavirus. After District 287 transitioned to remote learning, West continued to work on campus, where several students showed up at the building for some face time. Pleased by the gesture, he nonetheless had to shoo them away.

“Would that happen if there was a police officer here right now? No way,” he said. “You would not get kids to come to a building during a pandemic. The school is closed and they’re showing up.”

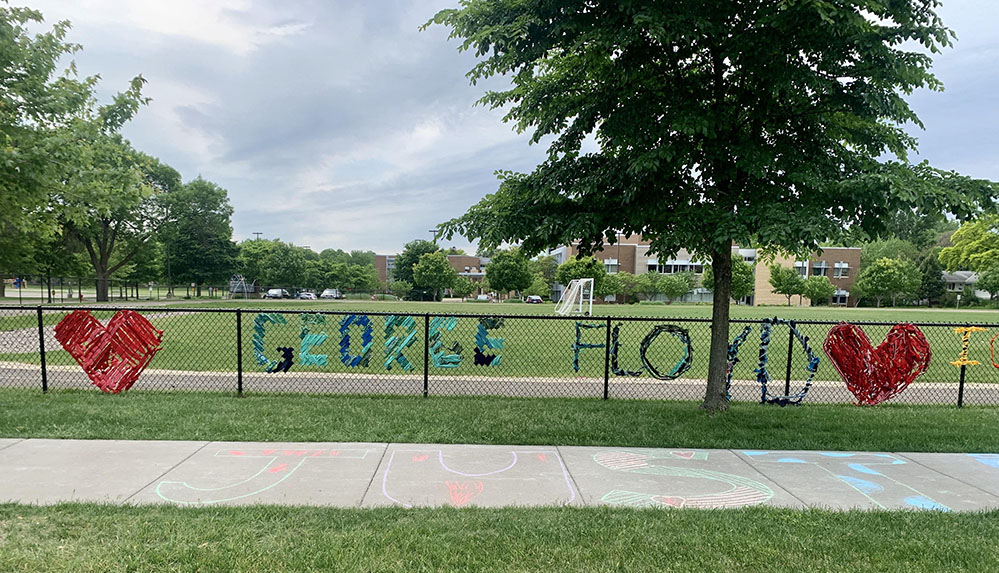

Whitlock, the safety coach, has also continued to connect with students during the closure. He joined a group of students outside the South Education Center after Floyd’s death and encouraged them to respond positively to the unrest. Weaving ribbons and strips of old blue jeans through a chain link fence outside the campus, Whitlock and the students spelled out Floyd’s name next to a heart.

Among those who helped was 20-year-old Keondré Cohen, who graduated from high school this spring. Before enrolling at a District 287 campus, Cohen attended a public school south of Minneapolis where school-based police gave students a “watch-your-back kind of mentality,” he said.

“They just look for the smallest excuse to come up to you and say something or … get you into trouble,” he said. But he observed a markedly different atmosphere at District 287, where safety coaches frequently approached students, asked about their lives and offered encouragement.

“Everybody in there, they cool,” he said. “They try to do right by people — Marcu [Whitlock] especially. That’s my boy.”

Rank and file

But not everyone in the district agrees it has taken a turn for the better.

“If you’re robbing people in here, if you’re running drug rings and things in here,” said paraprofessional Marcell Branch, then you should face the consequences.

For Branch, the issue is not a lack of empathy with what many of his students are going through. After all, he grew up in similar circumstances.

“If people don’t feel safe, then what’s the difference? If I feel at harm with a cop in the school and I still feel at harm with a cop not being in a school, then there is no change.”—Marcell Branch, paraprofessional at Intermediate District 287

A victim of child abuse, Branch found a family on the streets, running with a gang and spending several stints behind bars. He was 19 the first time he broke into somebody’s home, in the early 1990s. As the gang robbed the house, Branch pointed a 9mm pistol at a young boy’s head as his father listened to their orders.

Since then, he’s made a sharp turn in his life, and now he’s focused on improving student behavior.

In Branch’s view, safety coaches have struggled to maintain order ever since they replaced the police. He’ll never forget the time he got hit in the eye with a shoe “and didn’t even know it was coming.” While confronting an unruly student, Branch watched as the boy threw a shoe down the hallway — “a diversion for what he really wanted to do.”

“He’s got my attention focused on the shoe that he threw down the hallway,” said Branch, vice president of the local teachers’ union, which includes safety coaches. “All I felt was a sharp pain come across my eye.”

Such incidents are common. Removing officers from campus has not led to a downturn in educator injuries, district officials acknowledge. In 2015, before the officers were removed from district buildings, 367 staff injuries resulted in insurance claims exceeding $475,000, according to district data. Workers’ compensation claims spiked in 2018 — the year after the district began using safety coaches — when 699 staff injuries generated nearly $1 million in insurance claims.

“If people don’t feel safe, then what’s the difference?” Branch asked. “If I feel at harm with a cop in the school and I still feel at harm with a cop not being in a school, then there is no change.”

Lewandowski, the superintendent, acknowledged continued safety challenges in the district, which serves some of the region’s most volatile youth. But she denied that the spike in staff injuries is connected to the safety coach program. She argued that a shortage in mental health providers has made the district increasingly responsible for students with unmet needs, leaving officials struggling to address them. Meanwhile, she said, the most severe educator injuries transpire in a program for children with autism, where special education services — rather than arrests — are more effective at addressing challenging behavior.

The students “may be startled, something might change in their environment that’s subtle, and it can set up basically a behavioral interaction that can result in a concussion of a staff” member, she said. “Now, police officers really wouldn’t be much help in that kind of situation. We wouldn’t want police officers, for example, to come in and intervene from a police standpoint.”

A new direction

In many ways, the experiment taking place at District 287 goes against the national grain. Since 2018’s mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida, the trend among many districts has been to hire more cops, not get rid of the ones they have. Though only a fraction of public schools had police officers just a generation ago, their ranks have swelled in response to high-profile, but statistically rare, school shootings. Roughly 43 percent of K-12 schools — and 71 percent of high schools — have an armed police officer on campus, according to federal data. Meanwhile, some 1.7 million students nationwide attend schools with cops but no counselors, according to a recent American Civil Liberties Union report.

Civil rights groups and youth activists have long decried police presence in hallways, citing disparate arrests rates among children of color and violent interactions between officers and students. Meanwhile, there’s little evidence to suggest they make schools safer. In fact, some research suggests that campus-based police, often called school resource officers, could cause harm, including a decrease in high school graduation rates.

Floyd’s death has brought new energy to a movement to remove police from schools. When Minneapolis Public Schools ended its long-standing ties with the city’s police department, a “domino effect” swept the nation, said Maria Fernandez, senior campaign strategist at the Advancement Project, an advocacy group that has worked for years to remove cops from campuses.

Despite the push, educators — roughly 80 percent of whom are white — overwhelmingly oppose such efforts, according to a recent Education Week survey. Former police officer Sheldon Greenberg, now an education professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, is among those against removing officers from schools, and after policymakers spent decades promoting them as a way to prevent mayhem, he doubts parents will be willing to reverse course.

Disparate arrest rates among children of color is troubling, he said, and there’s sufficient room for reform. “The question is, are we throwing the baby out with the bathwater?” he asked.

Rather than replacing police with safety coaches, he suggested the district could employ both. Such “crisis intervention teams” already exist in some cities, where counselors and cops work in tandem. The role officers are supposed to play in schools should also be better defined, he said, with a more rigorous process for selecting those who work on the school beat.

As a growing number of district leaders move police out of classrooms, Lewandowski said, it would be “presumptuous of me to suggest” that District’s 287’s program would work elsewhere.

Even within the district, she doubts that police will ever be entirely absent from her schools, despite the growing call from youth activists. “I don’t think we’re ever going to say, ‘We don’t need to call 911.’”

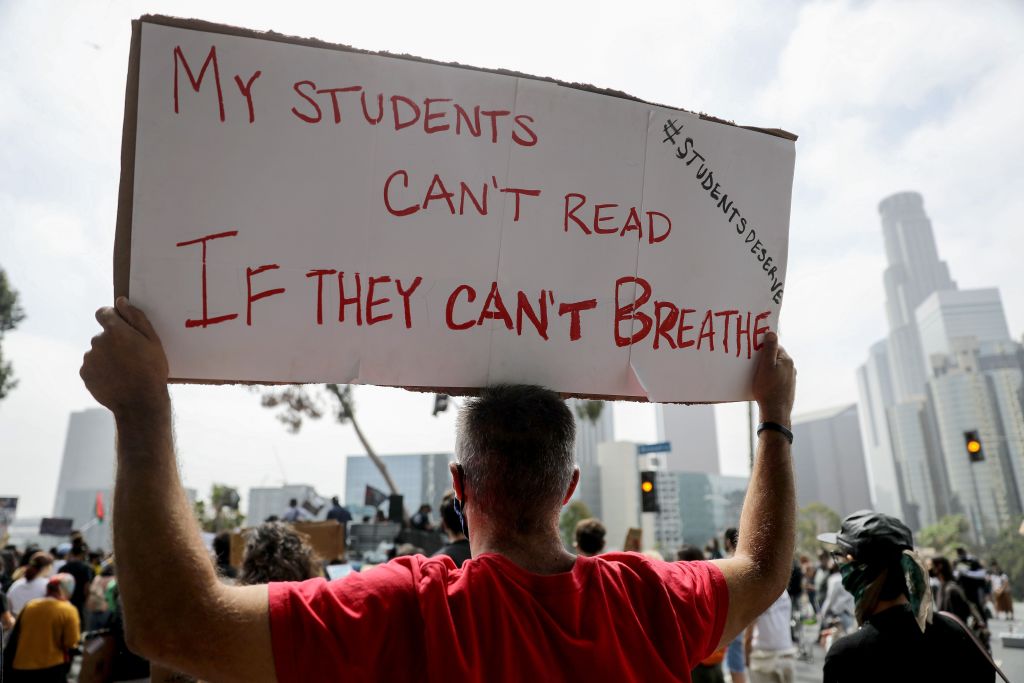

Lead image: DAl Seib / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter