Amid Surge in Stress During Pandemic, Sleep the ‘Magic Pill’ to Restoring Teens’ Mental Health, Experts Say

This story is published in partnership with The Guardian

When parents tell Denise Pope, an adolescent well-being expert, they’re worried for their children’s mental health, she responds with a question.

“How many hours are they sleeping?”

That catches many parents off guard, says Pope, co-founder of the Stanford University-affiliated nonprofit Challenge Success. Few see their teenage children’s mental health as linked to their sleep schedules. And besides, most parents go to bed before their high school-aged kids anyway, right? When Pope points out that teenagers need about nine hours of sleep each night, many parents scoff.

They shouldn’t.

As concerns for youth depression, anxiety and suicide have skyrocketed amid a deadly pandemic that disrupted schools across the country and isolated teens from their friends, researchers agree that consistent, sweet slumber can go a long way toward making students feel better.

In recent years, school leaders have highlighted that quality sleep is an important precondition for academic success, helping young people pay attention and retain material. In a 2019 effort to safeguard rest for teens, California pushed back school start times for middle and high school students statewide. But the mental benefits extend far beyond learning, experts say, emphasizing sleep as a key to healthy emotional regulation for young people.

By way of explanation, Pope offers a metaphor, which she credits to psychologist Lisa Demour.

“If you had sort of a magic pill that you could take that would help increase your mental health, increase your physical health, lower your stress, make you more efficient,” she says, most people would be itching for a dose.

Well, we do have that magic pill. “It’s called sleep,” says Pope.

But according to her research, teens are skimping on this vital resource, and the problem has only worsened with COVID-19.

In fall 2020, Pope’s Challenge Success team joined with NBC to survey 10,000 high school students on their well-being and academic engagement through the pandemic. They found that high schoolers were getting an average of 6.7 hours of sleep per night — well below the recommended nine-hour benchmark, which only 7 percent of students were hitting. Five percent of students regularly slept under four hours per night, the research team found.

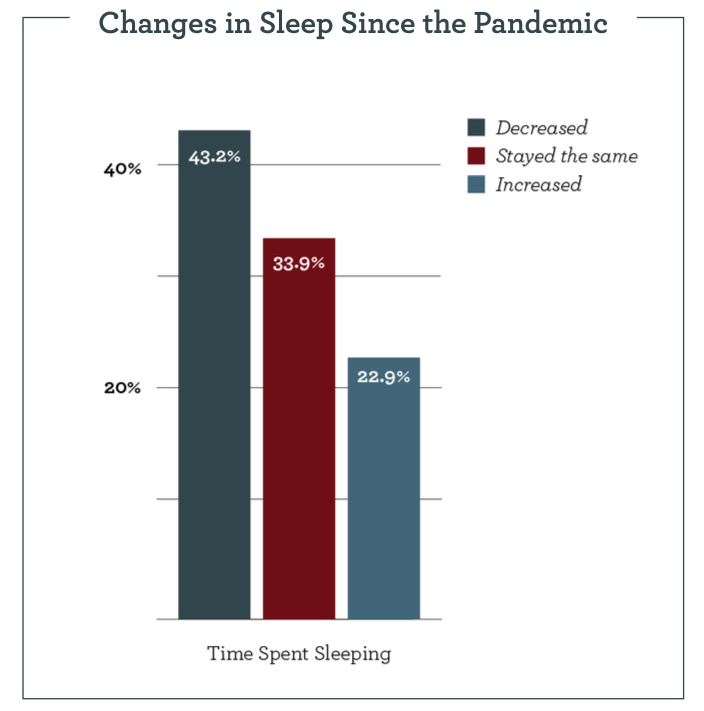

Even though remote school eliminated commutes for many students, 43 percent of high schoolers reported that they were sleeping less since the pandemic struck, compared to only 23 who reported sleeping more. Anecdotal accounts indicate that quarantine spurred many teens to stay up all hours of the night, sleeping sporadically throughout the day while their Zoom cameras were off and using naps as a coping mechanism when they started to spiral.

“My sleep schedule really went off the rails when the pandemic started,” Bridgette Adu-Wadier, now a senior at T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, Virginia, told The 74. During the day, on top of attending classes, she had to keep an eye on her two younger brothers, first- and second-graders who would constantly interrupt her with quarrels over toys, requests for help with schoolwork and messes to clean up in the kitchen.

Distracted days meant she frequently had to log late nights working to complete a never-ending stream of assignments. Sometimes, she would find herself nodding off while working. “It was just really hard managing my time with all the things that I had to juggle,” said Adu-Wadier.

The Virginia high schooler has not been alone. Students in a tricky AP course she’s enrolled in share a group chat, and on nights before assignments are due, messages buzz into the wee hours of the morning as peers scramble to finish. In the mornings, some of her friends can’t drag themselves out of bed for online class. Throughout this year, peers “definitely were in a similar boat,” says Adu-Wadier.

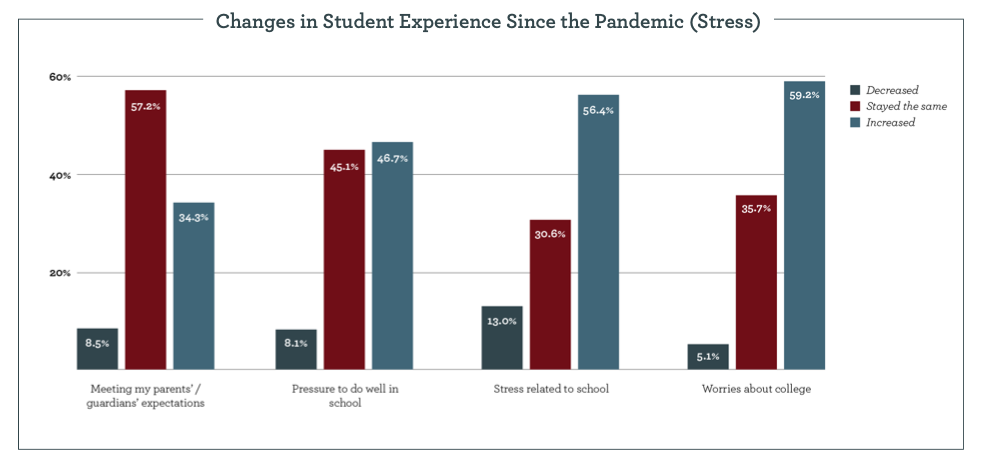

At the same time, isolation and worries for COVID-19 have exacerbated levels of teen stress and anxiety nationwide. Between April and October 2020, the share of mental health-related emergency department visits increased by 24 percent for children, and 31 percent for teens. Over 1 in 5 teenagers surveyed by EdWeek Research Center in April said their need for mental health counseling increased during the pandemic, compared to less than 1 in 10 who said it went down.

Based on increased demand for behavioral health services over the past four months, Colorado Children’s Hospital on May 25 declared a pediatric mental health state of emergency. The hospital’s chief medical officer said the situation is more severe than anything he has seen in his 20 years of practice.

Though experts say it’s too soon to tell whether the pandemic has spurred an increase in youth suicide attempts, parents of teens who took their own lives say that the circumstances of quarantine contributed to their children’s desperate condition.

Susanne Button, a clinical psychologist who directs high school programming for the Jed Foundation, an organization dedicated to preventing youth suicide, is especially worried for LGBTQ+ youth. Queer and trans teens struggled with high rates of suicidal ideation even before the pandemic, she says, and in the past year, many have been forced to quarantine with family members who do not understand their identities.

Working with such students, Button emphasizes the importance of good sleep hygiene.

“You can’t sleep off some of these stressors, but you certainly can link sleep into resilience,” she told The 74. “Adequate sleep for teenagers stabilizes mood and reduces irritability and depression.”

“Adolescents who don’t have enough sleep tend to actually engage in more high-risk behavior when they don’t feel mentally calm or happy,” continued Button. “Adolescents who get enough sleep tend to make better decisions and be less impulsive around risk-taking when they’re feeling stressed or distressed.”

But for students like Adu-Wadier, budgeting time to rest can be a challenge. She knows her well-being and mental health took a hit through much of the past year — she sometimes lacked patience, felt irritable and snapped at family members because she was over-tired — but it can be hard to find time to snooze when assignments are piling up, she says.

“[Sleep] ends up taking a backseat.” For many peers, she explained, the choice is a simple cost-benefit calculus: “They’ll feel tired, but at least they won’t be failing a class.”

In such cases, Pope of Challenge Success suggests a compromise. Every week, try to push bedtime just a few minutes earlier.

“Don’t let yourself look at that extra TikTok video, don’t stay up for the news, whatever it is. Just try to move that needle by 15 minutes at a time.”

Screen use before bed is something parents ought to monitor, Pope says. A mother herself, she’s had to institute a no-devices-at-night rule for her kids.

“Parenting needs to change as technology changes,” Pope says.

Of course, many youth live in conditions where it can be tricky to cultivate friendly sleeping conditions. Perhaps they’re staying with relatives or in a homeless shelter. Still, even small changes can help, says Pope, who recommends earplugs and sleep masks to mute outside stimuli.

As for Adu-Wadier, the long hours she logged studying for high-level courses have paid off. This spring, she earned admission to study at Northwestern University on a full scholarship.

On the night she got the good news, the college-bound senior didn’t stay up late celebrating. Instead, she tucked herself in at 10:30 p.m.

“I just went straight to bed,” Adu-Wadier remembers. “I didn’t spend a ton of time trying to do assignments or work on college applications because I didn’t need to do any more college applications. So I just attempted to go to sleep.”

Whether it was the news from Northwestern or a full night’s rest, the next day had a certain shine to it.

“I woke up feeling a lot different,” said Adu-Wadier. “It’s a very great feeling.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter