Youth Suicide: The Other Public Health Crisis

Youth suicide rates have been growing for more than a decade. With unprecedented isolation during the pandemic, the mental health ‘epidemic’ has become a political issue ahead of the election.

By Mark Keierleber | October 4, 2020Updated, Oct. 5

Brad Hunstable believes his 12-year-old son died of the coronavirus — just not in the way one might expect.

As the virus shuttered campuses nationwide and put students’ social lives on pause, the Texas father lost his son Hayden to suicide just days before his 13th birthday. In an emotional video posted online, Hunstable blamed pandemic-induced social isolation — and a fit of rage — for his son’s death earlier this year.

“Social isolation is hard enough for adults. It’s even more hard for our kids,” Hunstable said in the video, which noted that students’ interactions with their peers had been reduced to Fortnite and FaceTime. “I believe my son would be alive today if he was in school, and that’s not to discount massive suffering around the world around this virus.”

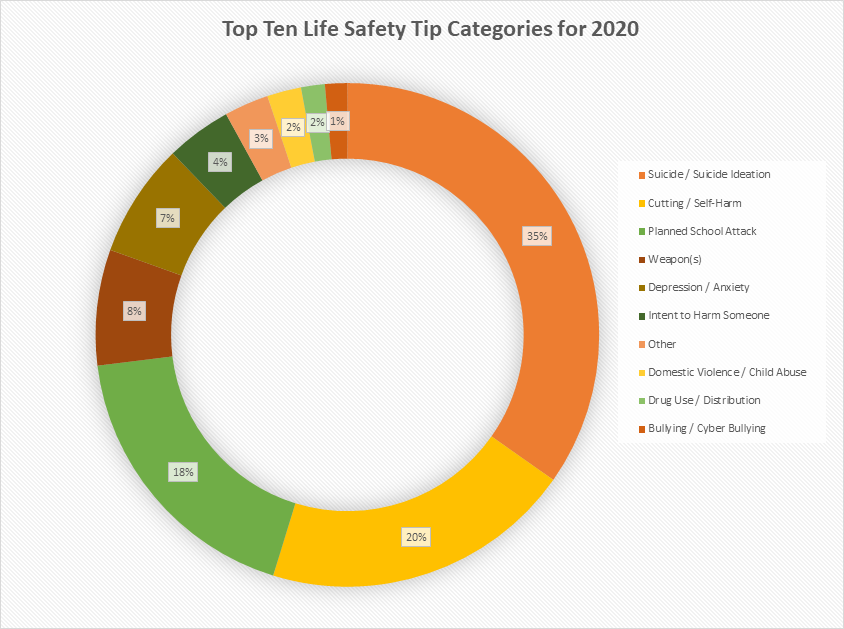

The national youth suicide rate has been on the rise for years. But now, in the months since the pandemic pushed students into haphazard remote learning and sent the economy into a tailspin, students say the unprecedented disruption has taken a toll on their emotional well-being. Researchers worry that a surge in youth depression and anxiety could drive a spike in youth suicide rates. The nonprofit Sandy Hook Promise, which runs the Say Something Anonymous Reporting System that allows students to file tips if they believe a classmate may harm themselves or others, has seen a 12 percent spike in suicide-related reports since March.

Yet the pandemic’s effect on suicide rates remains unclear, in part because federal data on the subject is released on a two-year delay. But it’s already become a political football ahead of the election next month. President Donald Trump has warned, in a bid to relax public health rules, that officials “cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself.” Lockdowns because of the virus, which has killed more than 200,000 Americans, could prompt “suicide by the thousands,” Trump has predicted. During a divisive presidential debate last week in Cleveland, Trump cited depression as a reason to reopen businesses. Trump himself tested positive for the virus late last week.

On Monday while hospitalized at Walter Reed Medical Center, Trump signed an executive order that creates a “cabinet-level working group” to study “the negative impact of prolonged shutdowns” on mental health, including for students.

Hunstable’s son took his life in April after breaking two LCD monitors over the course of several months while playing the video game Fortnite. His father also takes issue with the pandemic lockdowns, arguing that their use to prevent the virus was a “knee-jerk reaction.”

“I think it’ll be proven that they caused much more harm by doing the lockdown than other measures that would have been more rationally compassionate,” he told The 74. “I do believe we made a trade-off decision of one group suffering for another. I would argue from a policy standpoint we may have made the wrong choice about what was best for the future of this country.”

In the video he posted two days after Hayden’s funeral, Hunstable vowed to hold politicians accountable for their pandemic response, noting that if they’re not “a good enough leader,” he’ll spend his time and money “to get you out of there.”

Warning: This video contains graphic details of a child’s death by suicide.

Meanwhile, a new report by the nonprofit Everytown for Gun Safety, which advocates for heightened firearm laws, warns that a surge in pandemic-era weapon sales could lead to more youth suicide deaths at a time of heightened loneliness. Between 2009 and 2018, Everytown researchers found, firearm suicide deaths among young people 15 to 24 years old increased by 51 percent. The surge was even starker for youth 10 to 14 years old, increasing by 213 percent over the past decade. Guns are used in nearly half of youth suicides nationally, according to the report, and about 90 percent of attempts with firearms are fatal. Just 4 percent of suicide attempts not involving a firearm result in death.

With youth spending more time at home, Everytown has urged parents to ensure that their guns are locked, unloaded and separate from ammunition as a strategy to save lives — and has spent millions of dollars this year boosting candidates who back heightened firearm measures, most of them Democrats.

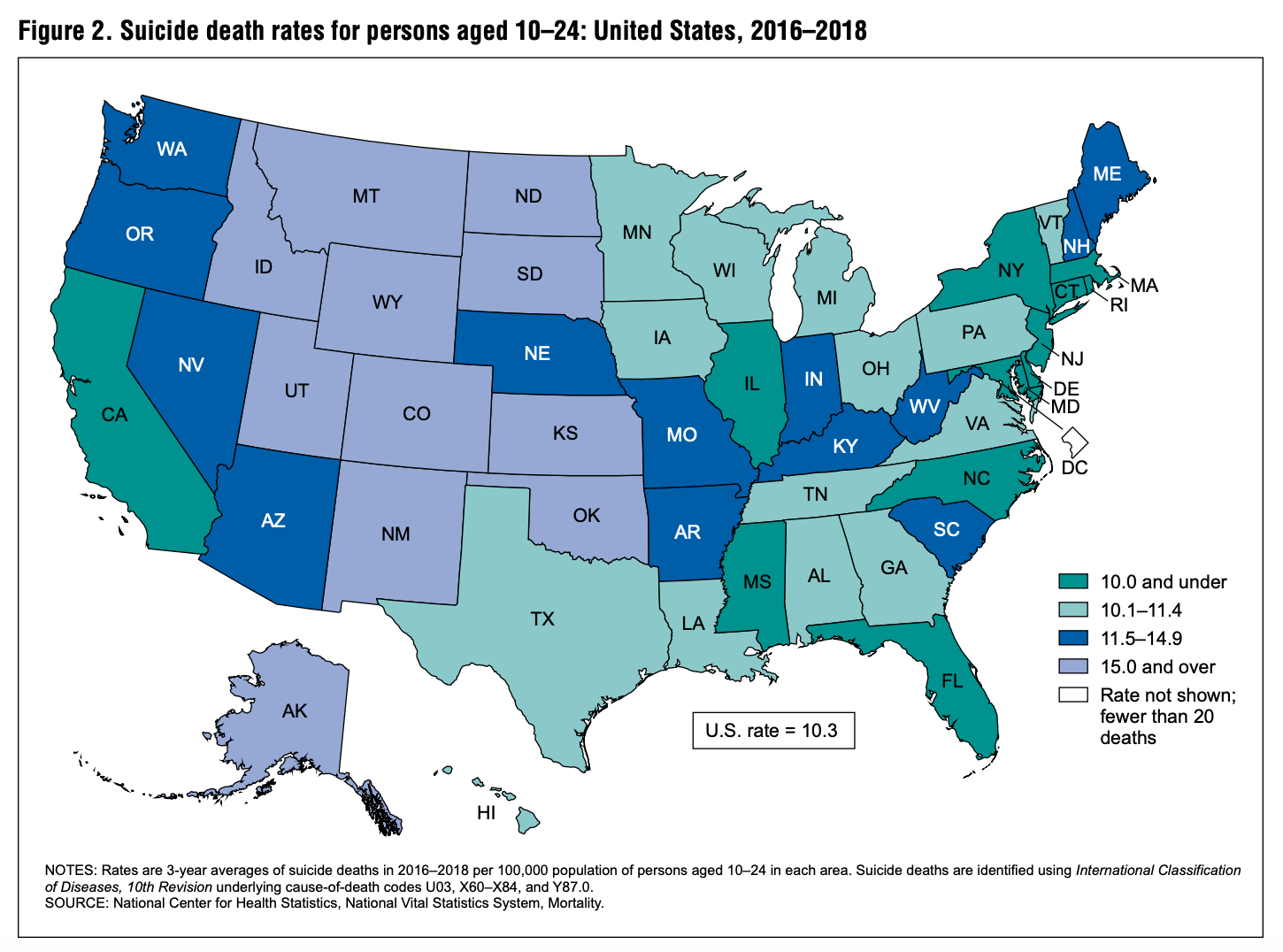

The alarm comes on the heels of a youth suicide crisis that’s been more than a decade in the making. Even before the pandemic, suicide was the second-leading cause of death among teenagers. Between 2007 and 2018, the suicide rate among Americans 10 to 24 years old surged by nearly 60 percent, according to new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Youth suicides grew fastest in New Hampshire between 2016 and 2018, but the highest mortality rates were clustered in Western states, including South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming and New Mexico. Alaska had the highest youth suicide rate, at 31.4 per 100,000 residents, the CDC found. A separate CDC report found that nearly 1 in 5 teens 14 to 18 years old “seriously considered suicide” in 2019.

On Sept. 29, the House voted unanimously on legislation that would encourage states to expand access to suicide prevention training in middle and high schools.

But Lena Heilmann, the suicide prevention strategies manager at Colorado’s Office of Suicide Prevention, urged against predicting whether the pandemic could lead to more deaths because suicide is rarely triggered by one factor. Heilmann noted that the pandemic has affected people differently. While school closures have been devastating for some students, they’ve been a source of relief for others.

“It’s really challenging to take something like COVID, that has impacts across both protective and risk factors, and to draw one-to-one conclusions about the impact that COVID is having on suicidal despair.” —Lena Heilmann, suicide prevention strategies manager, Colorado’s Office of Suicide Prevention

In Colorado, which has the country’s ninth-highest youth suicide rate, officials have put a greater focus on prevention in recent years following a rash of student suicide deaths in several communities. A report from the state attorney general’s office last year found that for some youth, suicide was “starting to seem normal in their communities.” During the pandemic, Colorado has not seen a statistically significant change in youth suicide rates compared with last year, according to state mortality data.

People who feel disconnected from those around them are at a heightened risk of dying by suicide, Heilmann said, and addressing feelings of isolation are key to prevention. Yet, while the pandemic has left some in a heightened state of isolation, others feel more connected because they’ve been able to spend more time with their families as a result of the crisis. Students’ educational experiences further complicate the matter.

“It’s really challenging to take something like COVID, that has impacts across both protective and risk factors, and to draw one-to-one conclusions about the impact that COVID is having on suicidal despair,” said Heilmann, who lost her 24-year-old sister to suicide in 2012. “For some individuals, school would be a significant protective factor if they feel connected to the school. If they feel disconnected from the school and school is a risk factor, remote learning might increase their protection.”

An epidemic before the pandemic

Hunstable said Hayden’s death was the result of a “perfect storm” of several factors.

For starters, the pandemic-induced social isolation prompted heightened anxiety, he said. But two mistakes — and his birthday just days away — led Hayden to make an impulsive decision that couldn’t be reversed.

In December, Hunstable gave Hayden a new monitor for Christmas. But when the avid Fortnite fan got mad while playing the game, he chucked the controller and broke the costly screen. The damage was irreparable. But by picking up additional chores around the house and being nice to his sister, his parents bought him a replacement. It didn’t last long. After breaking the second monitor, he took his own life. Hayden was already unable to have a birthday party because of social distancing, Hunstable said, and “went into the closet and got himself in a situation I believe he couldn’t get out of.”

In interviews with The 74, students from across the country reported feeling a sense of greater emotional distress because of the pandemic. Among them is Carrson Everett, a 17-year-old high school senior in Kingsport, Tennessee, who knows firsthand how social strain can lead students down a dark path. Because he’s gay, Everett said, he’s faced a barrage of harassment at school, even death threats. Faced with social rejection while in middle school, he attempted to take his own life.

“I just felt that there was no hope for me because I was a gay kid in the South,” said Everett, who currently attends Dobyns-Bennett High School in Kingsport on a hybrid schedule. This year, the pandemic-induced remote learning has caused major depression, he said. “Your social life is essentially over.”

Aashi Mittal, a junior from San Diego, California, said that attending school online every day has been exhausting and that she and her peers have struggled to cope with all of the changes. At her school, where teens face steep pressure to perform well academically, the stigma surrounding youth suicide prevents many students from reaching out for help, she said.

The changes — and uncertainties — have also taken a toll on college students in Idaho, said Lauren Axness, who studies communications at Boise State University. Axness and other college students are stressed out because the pandemic disrupted their college experience and could derail their career plans after graduating.

For researchers at Everytown, such anecdotes — and a surge this year in firearm sales — raise a red flag. Before the pandemic, an estimated 4.6 million children lived in homes with at least one unlocked and loaded gun, according to the advocacy group, and more than three-quarters of youth firearm suicides involve a weapon that belonged to a family member. Because youth suicide deaths are motivated by complex factors, limiting children’s access to firearms should be a fundamental part of prevention strategies, said Sarah Burd-Sharps, Everytown’s research director.

“Removing access to a firearm is actually the easiest and the quickest way to intervene, by keeping guns out of the hands of young people who are experiencing crisis,” she said. “That’s one reason why we’re really trying to sound the alarm about this issue.”

Everett, a volunteer for Everytown’s Students Demand Action, offered a similar message. While in middle school, he attempted to take his own life by overdosing on depression medications. Luckily, he survived.

Students who are contemplating suicide “think about every option on the spectrum,” he said. “You think of taking pills, shooting yourself, drowning yourself, hanging yourself. There wasn’t a limit for me of what I thought I was going to do. Thankfully my parents were smart enough to have their firearms locked up. That wasn’t really an option.”

Weapons, medication and a detailed plan to take their life

Jessica Neely and Bijal Mehta have seen the pandemic’s effects on youth mental health play out in real time. Both work at the Sandy Hook Promise Say Something crisis center in Miami, where specialists receive and respond to threatening tips. The reporting tool is available to students in more than 5,000 schools across the country, allowing teens to submit anonymous tips through an online form, via an app or by phone. They said the trends they’ve observed this year are terrifying.

The surge in suicide-related reports — up 12 percent compared with last year — is being driven primarily by students who are reporting on themselves. Beyond suicide reports, Sandy Hook Promise has observed a 20 percent uptick in “life safety” tips — which include those related to self-harm and child abuse where at least one life is considered to be in imminent danger — since the pandemic closed schools in March. Once a tip is reported, officials rush to provide help to the student in crisis, including in-school mental health care. Despite the increase in tips, it remains unclear to what degree they’re correlated with the national youth suicide rate, Neely said. But she does feel that the increased tip volume is related to the pandemic, with the most serious reports coming to their attention at night.

Among them are students who relied on teachers as an outlet when they were feeling depressed, as well as youth at risk of domestic abuse at home. In one tip through the Say Something system, for example, a student called to say that “no one cares” about them and that they just wanted “everything to be over.” A crisis center manager spoke to the student and determined they had weapons, medications and a detailed plan to take their own life. First responders were dispatched to the student’s home, and a school social worker began to work with the student the next day.

“Their words were, ‘I don’t know what to do anymore. I am constantly at the house with this person; every time I think about it, it just makes me want to hurt myself even more.’” —Bijal Mehta, Say Something crisis center specialist, speaking about a teen at home with their abuser during the pandemic

Another student reached out to say they were considering harming themselves with a razor after being subjected to sexual abuse. Their guardian, with whom the student lived, had sexually assaulted them three years earlier, and social isolation because of the pandemic amplified their interactions. After receiving the report, tip line officials notified first responders; the student was taken to the hospital and placed on a 72-hour suicide watch. The student’s guardian was arrested.

Mehta said the incident “really pulled on my heartstrings.”

“Their words were, ‘I don’t know what to do anymore. I am constantly at the house with this person; every time I think about it, it just makes me want to hurt myself even more,’” she said. “It was good to see that justice was served. Obviously that youth has a ways to recover and they have to take steps toward that recovery, but the fact that their abuser was removed from that home is absolutely a huge win for us.”

In Colorado, where the reporting tool Safe2Tell has allowed students to submit anonymous emergency tips for more than 15 years, officials have seen opposite results. Anonymous tips have long dipped during school closures including the summer months, Safe2Tell director Essi Ellis said. That trend held true in 2020: When the pandemic closed campuses in March, anonymous reports plummeted. Yet before and after the pandemic disrupted our lives, anonymous tips were most frequently about suicide.

“Suicide threats are becoming almost an epidemic nationally,” she said. “Youth are going through just as many stressors — if not more — than many adults are going through, and I think we’re just seeing it” play out.

‘Just check in’

Just five months ago, Hunstable had no idea he’d launch a nonprofit dedicated to youth suicide prevention. But two days after his son’s death, his video about his family’s tragedy went viral online. The video was meant to fill in his Texas town about what had happened to Hayden, but he found himself in the peculiar position of having a national platform.

With that platform, he founded Hayden’s Corner to raise awareness about the prevalence of youth suicide, help parents recognize warning signs and find a legislative solution. He said he plans to promote federal legislation that would require schools to teach kids about resilience, positivity and social and emotional development.

“I’m going to spend my time and my resources and my money to see if I can go and get Congress to listen,” said Hunstable, the co-founder and CEO of the electric motor company Linear Labs. He also co-founded Ustream, a live video streaming service that IBM purchased in 2016 for $150 million.

Noticing the pandemics’ effects on her peers, Mittal, the high schooler from San Diego, took suicide prevention into her own hands. Throughout September, she uploaded flyers to her Instagram account that highlighted key facts about youth suicide — and ways people can help to reverse the trend.

“Everyone has been feeling kind of down, and I’ve been feeling kind of down,” said Mittal, who also serves on the Sandy Hook Promise National Youth Advisory Board. Through the posts, she sought to “break that stigma of mental health and to really show people that everyone struggles and these are some things you can do to help.”

During an election year when the pandemic has thrust mental health into the political arena, Everett of Tennessee is working with Everytown’s Students Demand Action to drive voter turnout for candidates “that will actually put commonsense gun laws into action.”

But as the pandemic drags on, he offered a big piece of advice for parents: Ask how your children are holding up.

“I feel like we are all so busy and it’s hard to talk with a teenager — I know because I am one,” he said. “We can be a little difficult, but just check in; say, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’”

Click here to learn more about preventing youth suicide amid the pandemic.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Disclosure: Bloomberg Philanthropies provides financial support to Everytown for Gun Safety and to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter