Study: AI Uncovers Skin-Tone Gap in Most-Beloved Children’s Books

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated

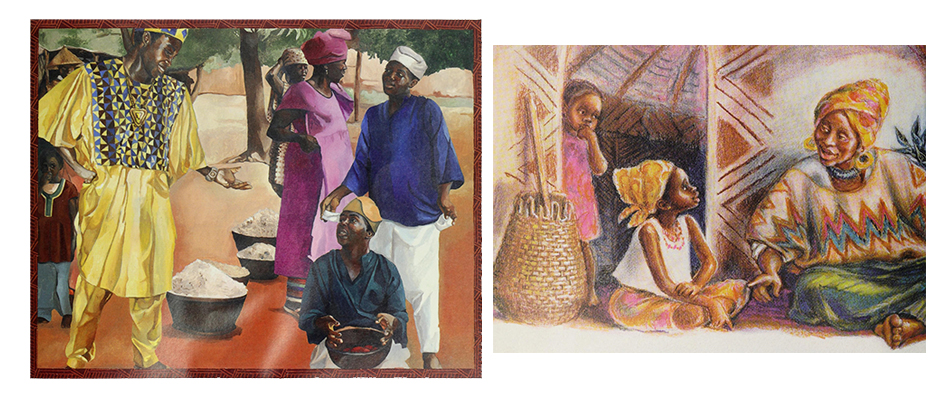

The most popular, award-winning children’s books tend to shade their Black, Asian and Hispanic characters with lighter skin tones than stories recognized for identity-based awards, new research finds.

The discovery comes on the heels of a half decade of advocacy to diversify the historically white and male-centric kids’ literature genre, leading to modest gains in racial representation. But now, a working paper recently published by Brown University’s Annenberg Institute raises questions about what, exactly, that representation looks like.

“There may be more characters that are classified as, for example, being Black, but they’re being depicted with lighter skin,” explained co-author Anjali Adukia, assistant professor at the University of Chicago.

Adukia and her team used artificial intelligence to analyze patterns in the images and text of 1,130 children’s books totaling more than 160,000 pages — far more data than manual methods could possibly crunch. Their code identified characters’ faces, assigned race, age and gender classifications, and calculated a weighted average for their skin tone.

The researchers found that, among books that won the Newbery or Caldecott awards, which comprise the lion’s share of purchases and library check-outs, the average shade for characters belonging to each racial category was lighter than those characters in books that won identity-based awards for race, gender, sexuality or ability representation such as the Coretta Scott King Award for African-American kids’ literature or the Stonewall Award for LGBTQ books.

The color analysis also revealed that, across all collections, children were persistently depicted with lighter skin than their adult counterparts. The messages sent by those portrayals worry Adukia.

“There’s … this notion of equating youth or childhood with innocence,” she told The 74. “But if innocence is equated with lightness or whiteness, what’s that implicit bias that gets baked into people’s minds?”

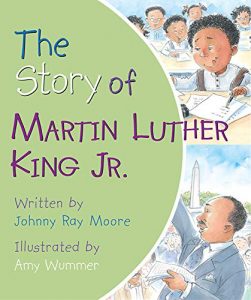

In many cases, said the professor, that pattern extends to adult characters that authors want to depict as moral or upstanding. Some books, for example, dilute Martin Luther King Jr.’s chocolate complexion to a light brown or beige, she said.

“We live in … a world that still sends the message that to be closer to white is to somehow be at an advantage,” Sharon G. Flake, author of the award-winning book The Skin I’m In, told The 74. “The whole notion that you are seen as … more valuable, more beautiful if you are lighter.”

The stories children read, said Flake, shape how kids come to understand the world and their place within it. Giving birth to an African-American daughter with a darker complexion inspired her to write a book featuring a dark-skinned Black girl as the protagonist to remind her child that she’s brilliant and beautiful.

“If you’re always left out of the story, then you start to think that you’re not important,” said Flake. But the power of books to reframe those societal messages, she added, is “huge.”

“When you’re able to read a book that actually does represent you, … you feel seen,” Edith Campbell, librarian at Indiana State University, told The 74. “You connect with it in a different way.”

But despite trend-setting titles, authored by Flake and many others, the children’s literature genre still has “a really wide gap in [racial, color and gender] representation,” said Adukia.

The dataset her team analyzed includes every children’s book published in the past century that won one of 19 different awards. Even from 2010 to 2019, their figures show, Caldecott and Newbery winners saw upticks in the share of characters whose skin color fell into the lightest tone group. They also saw a modest increase in the proportion of characters in the darkest skin tone — though the share remains less than in books winning identity-based awards — and a reduction in the percentage of medium shades.

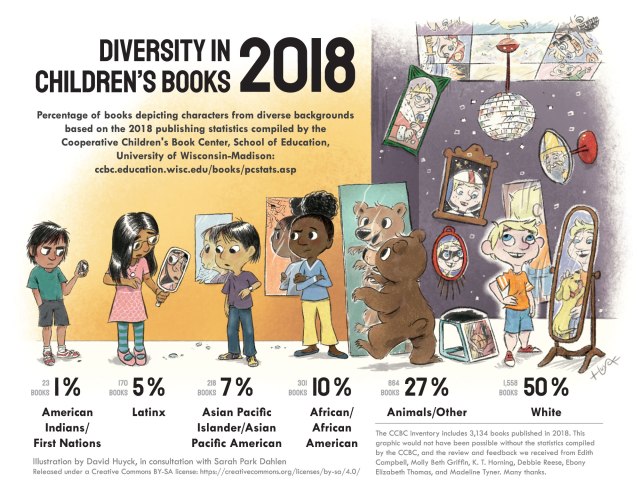

In 2018, half of children’s books depicted white main characters, while Black, Asian, Hispanic and Indigenous people led 10 percent, 7 percent, 5 percent and 1 percent of titles, respectively, according to numbers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cooperative Children’s Book Center.

“There are more books written with animal characters than there are with children of color,” said Campbell, remarking on the 27 percent share of stories with non-human protagonists in 2018.

The librarian, who launched the We Are Kids Lit Collective to boost diverse summer reading options, said she would give the recent progress to increase racial, gender and ability representation in the genre a D+/C-.

“There’s so much work to do,” she said, pointing to a string of new rules in red states and districts across the country ostensibly meant to limit critical race theory that disproportionately restrict the teaching of books written by Black, Indigenous, Hispanic and Asian authors.

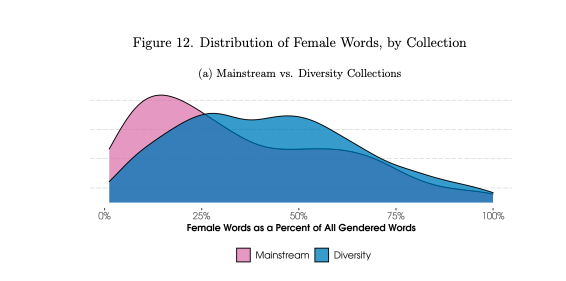

In addition to racial and skin-tone patterns, the UChicago and Columbia Teachers College research team also identified concerning trends in the portrayal of female characters in kids books. Girls and women, their data showed, were more likely to be represented in images than text. Out of all the award categories, those dedicated to representing female voices were the only group to have more words gendered as female than male, the researchers found, and that proportion amounted to only a slight majority.

“There may be symbolic inclusion in pictures without substantive inclusion in the actual story,” said Adukia. “It is really striking, this illustration that women should be ‘seen but not heard.’”

“I don’t think that [the imbalance between female representation in images versus text] is something that people necessarily are doing on purpose,” added co-author Emileigh Harrison, a Ph.D student at the University of Chicago. “But making this finding more visible might help those who are writing future books or publishers … think about it more carefully.”

If those in the industry can turn the worrisome patterns in racial, skin color and gender representation around, the potential impact can be enormous, Flake believes.

“Books work a lot of magic and they do a lot of healing,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter