Students at Colleges that Close Abruptly Less Likely to Finish Elsewhere

Outcomes even worse for minority students, study shows. Authors recommend greater state oversight, accountability

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Students who attended colleges that closed abruptly — some with just a day’s notice — between July 2004 and June 2020 were far less likely to re-enroll elsewhere and complete their studies compared to those whose schools shuttered in a more orderly fashion, a new study shows.

Outcomes were significantly worse for minority groups, according to the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association and the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, which released the findings earlier this week.

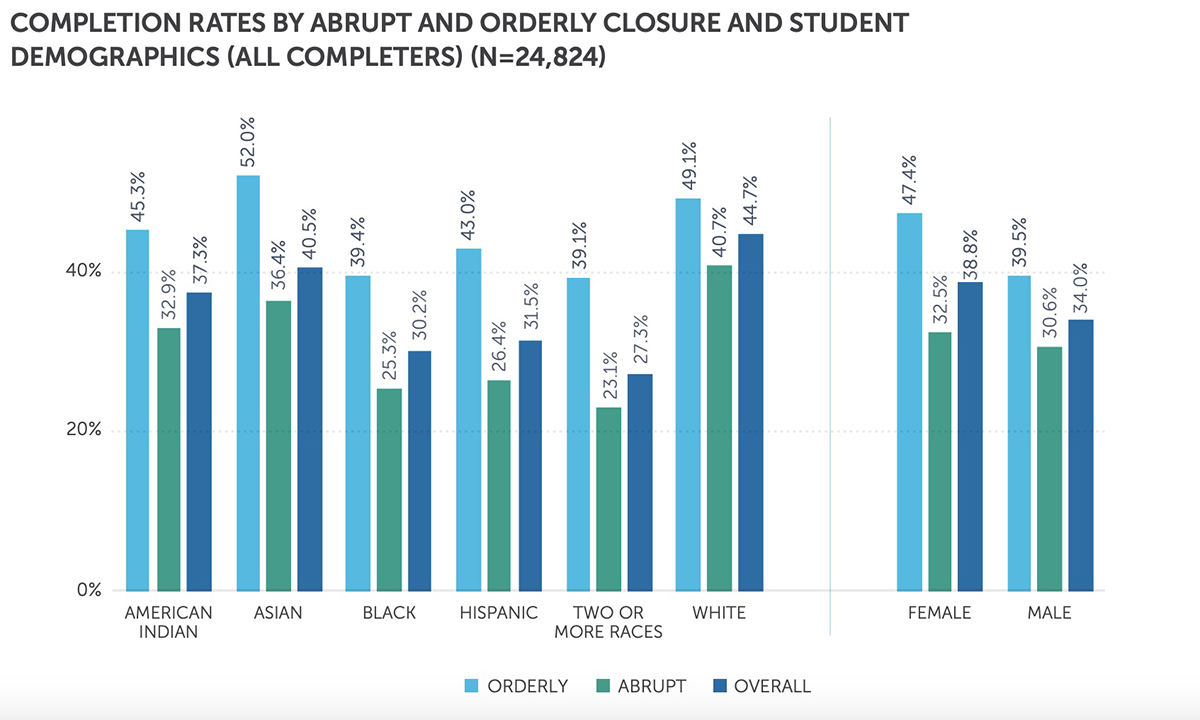

While 40.7% of white students who experienced an abrupt closure completed their studies at other locations, only 25.3% of Black students and 26.4% of Hispanic students did the same. Just 32.9% of American Indian and 36.4% of Asian students also met that goal.

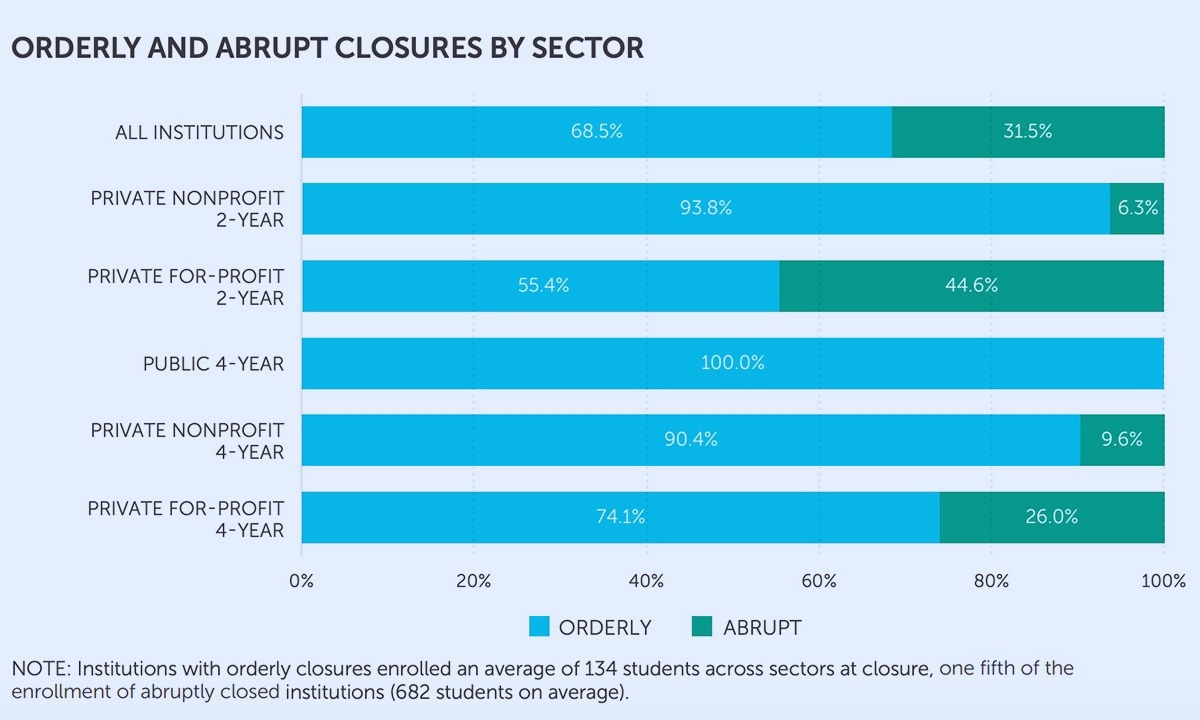

The findings were based on the records of 143,215 students at 467 institutions across the country, nearly half of which were in the private, for-profit, two-year sector. Nearly 55% were female, 25% were white and 34% were 30 or older at the time. Almost 83% experienced closures at for-profit institutions.

“Less than half of those students — 47% — ever re-enrolled at another post-secondary institution,” said Doug Shapiro, the Research Center’s executive director, speaking of the students as a whole. “So, their school’s closing effectively closed the doors on the student’s educational dreams.”

Of those who did re-enroll only 36.8% earned a postsecondary credential: More than half left their new school without earning any credential, Shapiro said.

Roughly 100,000 of the students in the study attended campuses that closed abruptly, leaving them to scramble for transcripts that were often unavailable, making it even more difficult for them to pursue their degrees.

Researchers say states can play a greater role in preventing abrupt closures by enacting more stringent initial authorization practices for these colleges and by providing oversight in the years that follow, in part by monitoring student complaints and implementing a regular, more rigorous renewal process.

Rachel Burns, a senior policy analyst with the State Higher Education group, acknowledged that it can be difficult for students to take a more proactive role around the issue. While private for-profit schools have long been criticized for predatory practices, ensnaring thousands, including minorities and military veterans, into expensive, worthless programs, many of these schools still have appeal.

“There are already reasons to be skeptical of some of those institutions but sometimes those are the best options for students that need flexible schedules,” Burns noted, adding students would be wise to keep current copies of their transcripts and educate themselves about the transfer process.

Not only did closures disrupt or end students’ education, but it left them in debt. The federal Department of Education allows for the discharge of federal student loans for eligible students when their schools close, the report states, but not everyone qualifies or successfully completes the process.

A Government Accountability Office report from 2021, researchers said, shows that of 246,000 borrowers who weathered school closures between 2010 and 2020, only 80,000, or 32.5%, had their loans forgiven. These students, the GAO reported, collectively owed $4 billion, with the median debt hovering around $9,500 per student.

The study found, too, that private for-profit, two- and four-year institutions enroll a disproportionately large number of students of color: in 2018, 12% of all students of color enrolled in postsecondary institutions eligible for federal student aid attended for-profit institutions.

Re-enrollment rates overall were highest among women at 49%, white students at 62.5%, and traditional college-age students with the youngest, those 18-20, fairing the best at 54%.

Those who re-enrolled within one to four months were the most likely to earn a credential, coming in at 47.6%: Those who waited a year or more were the least likely at 18.7%.

In several ways, the long-term findings on college closures mirror the nearer-term impact of the pandemic when college enrollment plummeted, particularly at community colleges which serve many low-income students of color.

Nearly 12,000 campuses of institutions of higher education closed during the years examined by the study — often because of loss of accreditation related to financial challenges — and more have been added to the list since then, including Lincoln College of Illinois.

The 157-year-old school survived a major campus fire in 1912, the Spanish flu of 1918, the Great Depression, World War II, the 2008 global financial crisis, according to its announcement, but it could not overcome the economic devastation of the pandemic and the impact of a crippling cyberattack.

The school, which served 756 students in 2019, many of them first-generation college-goers, shuttered in May. Roughly 44% of the student body was Black.

Student Jaylah Bolden, who has since transferred to another school, told The Washington Post earlier this month that many of her friends were not able to make that leap and now are not enrolled anywhere.

“They lost their faith,” she said. “We didn’t give up on school. School gave up on us.”

Researchers said abrupt closures in the private, for-profit four-year sector had the worst and most profound impact on re-enrollment rates.

This marks the first of three reports. The second, expected in early 2023, will quantify closures’ impact on students by comparing them to those whose schools did not shutter. The last will examine how state policies affect student outcomes, comparing students who experienced closures in states with stringent protections against those attending schools without such safeguards. No release date has been set for the final report.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter