New Study: Low-Income Chicago Students 40% More Likely to Earn Bachelor’s After College Prep Program

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

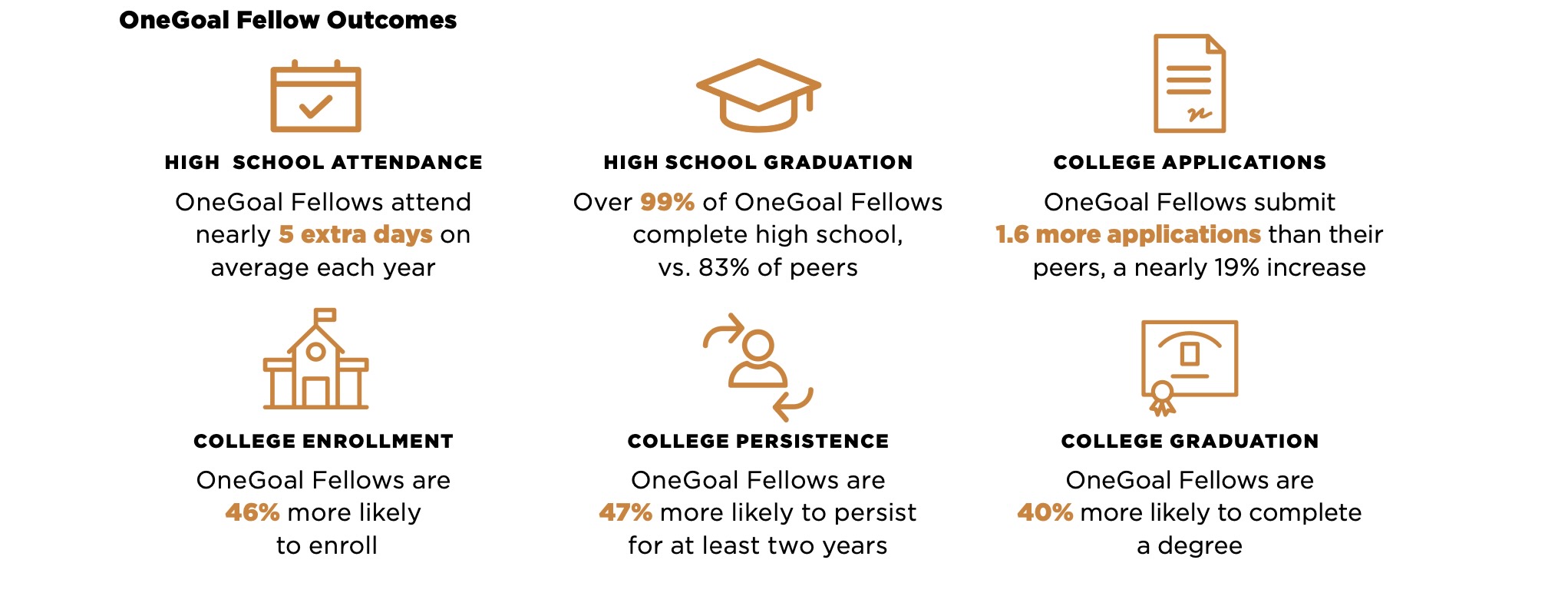

A study of more than 7,000 Chicago Public High School students who enrolled in a program meant to improve college graduation rates for low-income participants showed they had a 40% greater chance of earning a bachelor’s degree than their peers.

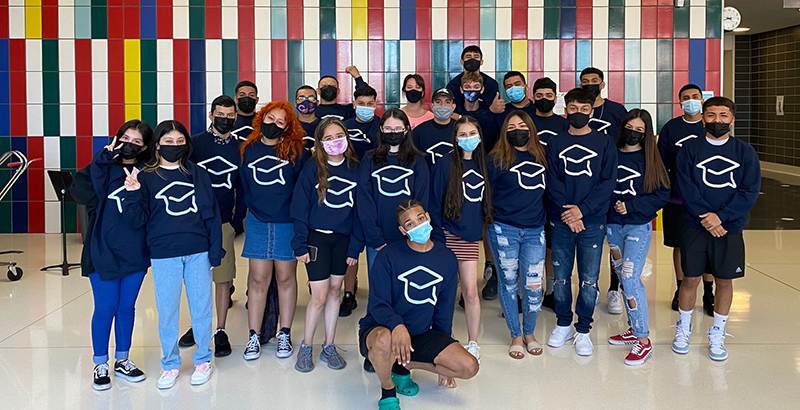

The program, called OneGoal, founded in 2007, spans students’ junior and senior year of high school and their freshman year of college. It began with a class of 25 and now serves nearly 14,000 students nationwide — including in Chicago, Houston, New York City, Massachusetts, Metro Atlanta and the Bay Area — with plans for expansion.

The study, conducted by the University of Chicago Inclusive Economy Lab, examined the outcomes of students who were slated to graduate from high school between 2011 and 2020. It found OneGoal students were also 46% more likely to enroll in college, and 47% more likely to come back for their sophomore year than similar students who did not go through the program.

“I would tell any high school student who would listen, ‘Do not turn your back on OneGoal,’” said Mariam Ajose, 22 and a senior at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “They are a huge gateway to success in college or whatever goal you choose to pursue.”

Ajose credits the program for her success: Both of her degrees — the associate’s she has already earned and the bachelor’s she is working toward — will have been completely funded through sources she discovered through OneGoal.

Students learn about the program in informational meetings their sophomore year of high school. Some are selected for participation and others opt-in.

Participants take a OneGoal class daily for two years: They spend their junior year reflecting on their own backgrounds and how they would like to use their talents to augment their communities. They close out the year with a list of colleges they’d like to apply to and spend their senior year examining each school even further before completing their applications — transcripts, recommendation letters, essays — and financial aid forms. Each OneGoal fellow is assigned a counselor to guide them through the process.

Students’ freshman year of college is different: it consists mostly of individual check-ins with OneGoal staff tailored to participants’ needs.

Vanessa Lee, a teacher in the Chicago Public Schools, started working with the program in 2013. She said many students who enroll in OneGoal see themselves and their life experience in a negative light and that the program helps them view their challenges as assets, proving they already have what it takes to overcome obstacles.

“There is a deficit model when we think of low-income, first-gen students,” she said. “OneGoal is flipping the script on that, telling students to look at all of the things they do possess and strengths they do have.”

Melissa Connelly, chief executive officer at OneGoal, understands how students from low-income communities might lose faith in themselves and in their education. Connelly missed 53 days of 8th grade and was on the road to becoming a high school dropout. She suffered from depression and had an overwhelming feeling of hopelessness about her future: Like many of the students OneGoal serves today, she couldn’t imagine living past age 18. So why bother investing in her education?

It wasn’t until she met a compassionate social worker that she was able to turn her life around.

“She helped me see what was possible for myself,” Connelly said, adding that it took time for the woman to earn her trust. “Like the old education saying goes, kids don’t care what you know until they know that you care.”

After gaining her confidence, the counselor moved onto some of the more practical matters of shaping Connelly’s future by working on her financial aid documents.

OneGoal, a nonprofit funded in large part by philanthropic contributions, works on that same principle, winning students’ trust before shifting to the academic tasks at hand.

“That’s why OneGoal is so special,” Connelly said. “When you walk into a OneGoal classroom, you will hear the word ‘family’ at least once.”

Kelly Hallberg, scientific director for the Inclusive Economy Lab, said researchers compared OneGoal fellows to students who came from a similar demographic: They attended the same Chicago high school, had similar past academic performance, came from a similar neighborhood, were of the same race or ethnicity, and had the same rates of housing instability and Individualized Education Plans.

“There is a growing body of evidence that shows holistic programs that touch many aspects of kids’ lives — shaping their mindset, navigating the college selection process, the financial side — move the needle more than a program that targets one aspect, as in, just tutoring, application support or funding.”

The findings were so remarkable that Hallberg doubted their accuracy.

“When we first saw the results, I said, ‘We need to kick the tires on this, make sure these numbers hold up because they are pretty big,’” she said. “But, the results are consistent.”

Ajose said the program taught her far more than she anticipated, including how to find the college that best suited her by considering the local cost of living, student-professor ratio, graduation rate and the quality of the program itself. OneGoal staff can take kids on college trips: The organization also partners with universities for tours.

Most important, the kinesiology major said, she felt like her OneGoal instructors truly cared about her. They noticed, for example, when her grades fell and she could come to them to talk about problems at home.

Their involvement didn’t end when she aged out: OneGoal still helps her pay for books even though she is in her senior year, Ajose said.

Elijah Wright-Jefferson, 23 and a student at Illinois State University in the town of Normal, hails from the South Side of Chicago. Resources in his community were few, he said: Nearly a dozen of his high school classmates died by the time he reached his mid-20s.

“People get desperate and upset, which leads to violence, stealing and a lot of anger,” he said. “That was the environment I had been around my entire life. I had never been anywhere else.”

His high school counselor knew he could do better: She asked him five times to join OneGoal before he relented.

Not only did the program teach him about the college admissions process, but introduced him to all different types of people — including basketball legend and community investor Magic Johnson — with myriad jobs, who lived and thrived in various parts of the city.

“During college, they helped me a ton,” Wright-Jefferson said, adding he’s thrilled to participate in the program to this day, encouraging other students to join and stick with it.

Lee, who teaches in the Chicago Public Schools, credits OneGoal for its adaptability: The program has changed dramatically through the years, building on teacher and student feedback.

“It has become much more inclusive,” Lee said, broadening its focus, upon teacher and students’ request, from four-year colleges to other routes to success, including associate’s degrees, trade schools and the military. “It puts students at the center of their own plan. It validates that there are alternative pathways — and one is not better than the other.”

She attributes at least a part of its success to the fact that it utilizes teachers who already work inside the schools: They know and have relationships with the students they serve.

OneGoal is currently working with the Illinois State Board of Education to partner with 24 districts across the state. It is spending this first year providing strategic postsecondary coaching for district and school leaders to build the infrastructure needed to launch the program before offering the class as an elective in those school systems. It will also add districts in the six states it already serves, plus Kentucky.

Connelly estimated there are roughly 1.4 million low-income 11th graders in the nation’s schools. OneGoal hopes to reach half of them in the next 10 to 15 years: It aspires to grow from 14,000 to 50,000 students in the next three years.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter