National Analysis: They Said Letting Transgender Girls Play Would Drive Athletes Away from HS and College Sports. It Didn’t

Exclusive: Data show girls' sports grew 13.4% nationwide over the past decade

By Beth Hawkins | October 19, 2022When Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a state law outlawing trans student athletes in April 2021, the bill’s author hailed her as a champion of girls and women. “I want to thank Gov. Ivey for her leadership and for protecting the rights of Alabama’s female athletes,” Republican state Rep. Scott Stadthagen tweeted.

Like Republican lawmakers throughout the country, the Alabama officials who pushed to prevent transgender youth from participating in sports said the move was necessary to keep cisgender girls from being driven out.

The state’s junior senator, Tommy Tuberville, went further, leveraging his fame as a college football coach to try to institute a nationwide ban. Within weeks of his swearing in, “Coach,” as Tuberville is known, signed on to the Protection of Women and Girls in Sports Act and later tried to condition approval of pandemic aid on schools’ exclusion of trans athletes.

On the campaign trail, Tuberville depicted the issue as urgent: “I am against this transgender, guys turning into women and winning all these state championships all over the country.”

But there is no evidence that trans athletes are crowding out anyone. In fact, the Alabama High School Athletic Association told a reporter last year that it did not know of any transgender student athletes, past or present, in the state.

More to the point, an analysis by The 74 has found no basis for claims that allowing trans students to compete would drive large numbers of athletes away from girls’ high school and college sports. In reality, the opposite is true: In the decade since collegiate sports officials created a set of rules on participation by trans athletes, the number of female students playing sports has skyrocketed in many places. These include many of the 18 red states that in the last few years enacted bans anyhow. Nationwide, the number of female student athletes has risen by more than 13%.

In sports-obsessed Alabama, participation in girls’ high school athletics shot up more than anywhere else in the nation, rising by 63% between 2012-13 and 2018-19. Participation among high school boys was up 45%.

The 74 asked for comments on the discrepancy from Ivey, Stadhagen, the Heritage Foundation (which has issued a number of reports on “radical gender ideology”) and the Alliance Defending Freedom, which has drafted language for trans ban bills used around the country, defends the laws in subsequent suits by students who can no longer play as a result and filed a suit arguing that trans participation violates the rights of cisgender females. None responded to repeated requests.

Claims of future damage

As bills excluding transgender students from playing on sports teams that match their gender identity have been proposed throughout the country over the last two years, the issue has been framed as a future problem, one that could come to pass if nothing is done to bar trans student athletes.

Insisting that students who were assigned a male sex at birth possess innate physical advantages, supporters of the legislation say that without the new laws, cisgender girls will lose out on trophies, scholarships and other opportunities. Using this argument, since 2020, 18 states have passed legislation banning transgender students from competing on girls’ and women’s teams — and, in some cases, on boys’ and men’s teams, too.

An investigation last year by USA Today found that as lawmakers introduced the measures in statehouses, they often cited supposed damage done to cisgender girls by trans athletes who turned out not to exist or, in a handful of cases, stories about contests won by trans athletes whose records of wins and losses were mischaracterized.

The debates have also ignored or glossed over a growing body of research suggesting that transgender girls and women do not enjoy physical advantages over cisgender female players — especially when their body’s production of testosterone has been suppressed.

The International Olympic Committee, which has had rules governing allowable hormone levels of elite athletes for nearly two decades, last year eliminated requirements that gender-nonconforming competitors submit to exams. Noting that there is no medical consensus that testosterone levels alone confer an unfair advantage to transgender athletes, the new framework says authorities overseeing individual sports should determine eligibility, with no presumption of athletic superiority.

A handful of wins by transgender athletes over the last six years — most notably, former University of Pennsylvania swimmer Lia Thomas’s March NCAA Division I championship — have been met by critics who question whether an aspect of their physique gives them an advantage. But there are very few formal complaints, much less documented instances, of a cisgender girl or woman losing a title or scholarship because of trans competitors.

‘If you build it, they will come’

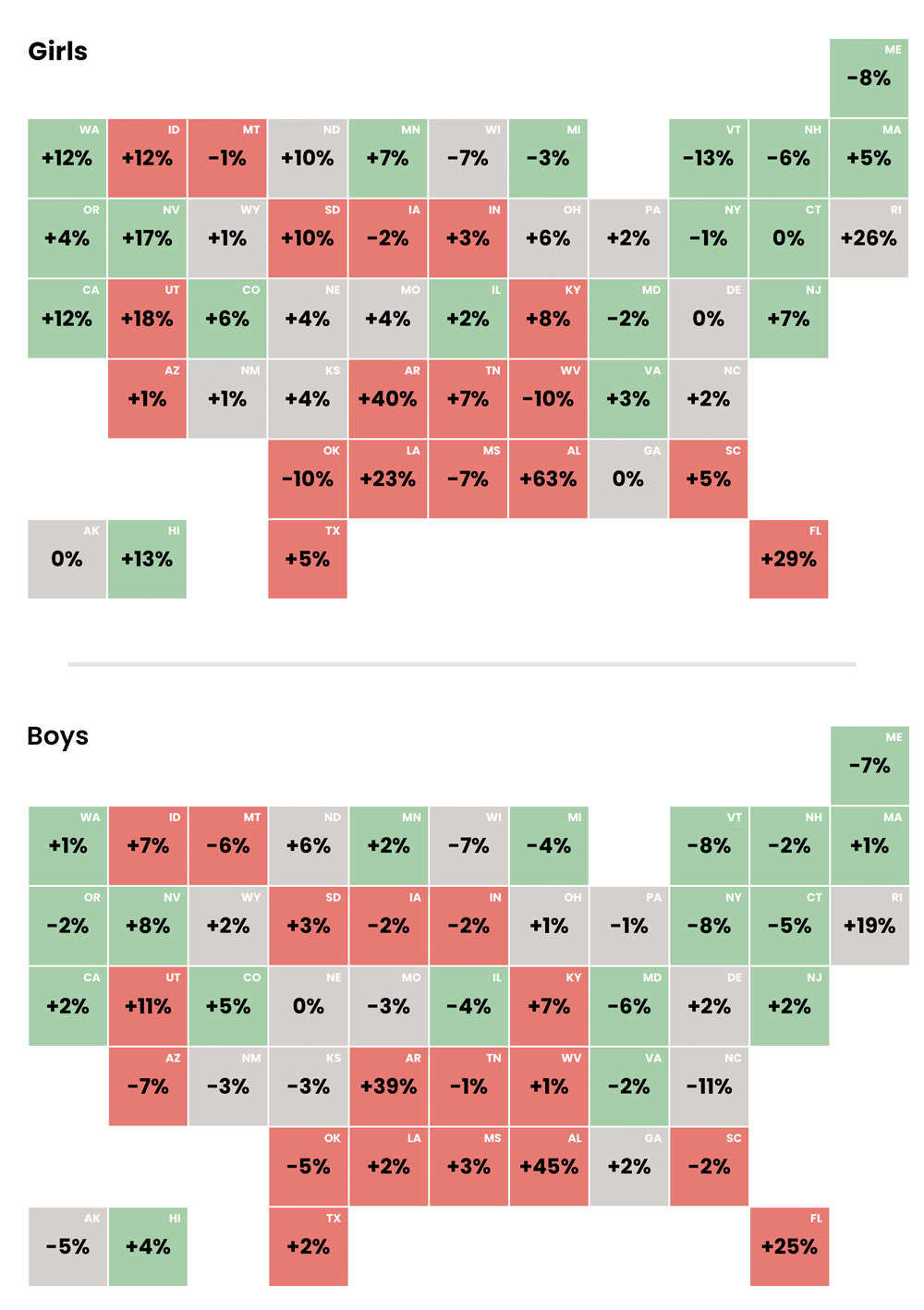

Still, even as the furor continues unabated, data analyzed by The 74 show that in more than 10 years of transgender inclusion, no harm has come to girls’ or women’s sports at the high school or college levels. Using research from the Center for American Progress as a jumping-off point, The 74 examined records from the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the National Federation of State High School Associations, calculating the percentage changes to boys’ and girls’ participation in high school sports by state.

Both datasets show increases — in many cases, by double-digit percentages. So does a more limited set of statistics compiled by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

–

Data Analysis

High School Sports Participation Rates 2012 – 2019

Percentage changes in participation in high school sports, based on statistics from the National Federation of State High School Associations. State laws and policies from LGBTQ rights databases maintained by the Movement Advancement Project. State-by-state estimates of transgender youth populations from the UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute. Maps by Eamonn Fitzmaurice / T74

–

The datasets differ in how information is collected and what it depicts: The high school federation compiles data showing the number of competitors in each sport by state, so an athlete who plays more than one sport may be counted more than once. Because of the pandemic, the organization was not able to gather data for the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years.

The federation recently released figures showing participation in student athletics in 2021-22 was down 4% from 2018-19, dropping from 7.9 million to 7.6 million. A spokesman said the organization believes the dip is likely temporary and attributable to the pandemic, given how many schools were unable to offer comprehensive athletic programs during COVID.

But between 2012-13, when a set of rules enabling transgender athletes to compete began to be adopted, and 2018-19, the year before pandemic school closures, participation in high school girls’ sports increased by 13.4% nationwide, according to federation statistics. Within that average, large increases were seen — even in a number of states that later went on to adopt anti-trans policies.

In Arkansas, which has gone beyond banning trans athletes to prohibiting gender-affirming medical care for youth, participation rose 40%. In Florida, where a new “Don’t Say Gay” law and a trans sports ban are now in effect, participation rose 29%. In Louisiana, where Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards this year chose not to veto a law excluding trans girls from sports, female athletics was up 23%. In Utah, where lawmakers voted to let a committee examine transgender students who want to play sports, girls’ participation was up 18%. In Idaho, which adopted the first statewide trans exclusion law in 2020, participation was up 12%.

Girls’ participation increased in 13 of the states that have enacted trans sports bans and fell in five. Of the states that do not specifically exclude trans kids from sports, 22 saw more girls participate, seven saw fewer and four had no change.

These dramatic increases mirror a rise in the number of boys playing high school sports in the same states, which researchers say is likely connected to their sports-centric culture. Under Title IX, the federal law that prohibits schools that receive federal funds from discriminating on the basis of sex, states are required to provide equal athletic opportunities to male and female students. So when schools in a football-obsessed place such as Alabama add boys’ football teams, they must create athletic programs for girls as well.

“The common mantra is, if you build it they will come,” says Anna Baeth, research director of Athlete Ally, an organization that has worked with Olympic and collegiate sports officials to develop LGBTQ-inclusive policies. “We’ve seen this across the board with girls’ and women’s sports — where there are opportunities, when there are teams, girls and women show up.”

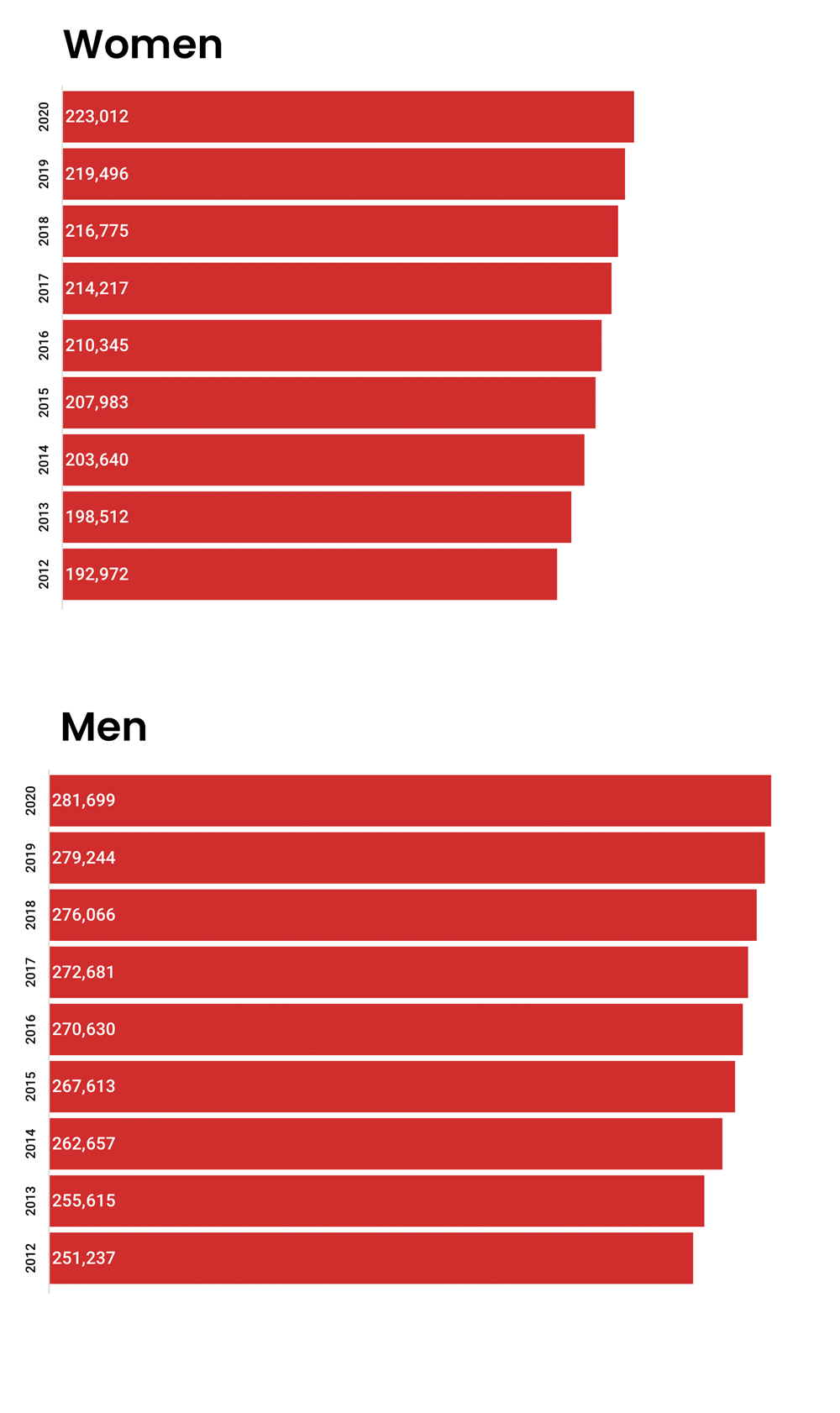

On the collegiate level, from 2012 to 2020, the number of athletes overall rose from about 444,000 to more than 500,000, according to the NCAA. During that time, the number of female athletes rose 14%, from 193,000 to 223,000, while participation in men’s sports rose 12%, from 251,000 to 282,000.

Data Analysis

College Sports Participation Rates 2012 – 2020

CDC statistics suggest that over the last decade, more high school girls are playing sports even as the number in boys’ sports has fallen. In its periodic High School Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, which counts only states that agree to participate and to ask residents relevant questions, the number of female high school students overall who reported playing one or more sports between 2011 and 2019 rose from 53% to 55%, while the number of boys fell from 64% to 60%.

Few LGBTQ kids on the playing field

But while female participation in student sports overall has boomed, the number of openly transgender athletes has not. For one thing, says Baeth, there simply are not very many. While there is no system for tracking how many gender-nonconforming students play sports, estimates are that transgender people make up less than 2% of the population at large and about 1.7% of university students.

As of 2021, more than 87,000 trans students ages 13 to 17 lived in the states that now ban some or all of them from participating in athletics. That’s slightly more than half as many as the 160,000 high school-aged trans students who lived in states where the rules allow them to play. But despite NCAA guidance about fairness and inclusion, few take part.

“Collectively, we did not see a huge rise in the number of trans athletes competing at [the collegiate] level,” says Baeth. “Those numbers have been incredibly low for the last 10 years.”

Research has long established that LGBTQ students fear school sports and athletic facilities, where they are likely to be harassed. According to researchers at GLSEN, which works to create inclusive school climates, in 2019, 44% of LGBTQ students reported avoiding locker rooms, while 71% of trans boys and 73% of trans girls said they did. Majorities of trans and nonbinary students also avoid gym classes.

Fifty-two percent of trans boys and nonbinary students and 58% of trans girls say they have been barred from locker rooms. More than 10% of LGBTQ students says school staff or coaches discouraged them from playing sports specifically because of their identities, a figure that is much higher for trans and nonbinary youth than for their cisgender peers.

According to Baeth, lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer youth are twice as likely as their straight peers to leave sports, while trans and nonbinary students are four times more likely.

Just 16% of LGBTQ students said they would be comfortable talking to a coach or gym teacher. Students’ comfort levels, not surprisingly, are higher in schools where they hear fewer homophobic remarks. More than a third of queer youth said discriminatory policies toward LGBTQ students in general are one reason they do not expect to finish high school.

Especially when a child’s family is not accepting, a school culture that affirms gender-nonconforming students can literally make a life-saving difference. In a 2022 survey administered by The Trevor Project, which addresses suicide and mental health crises in LGBTQ youth, 59% of trans boys and 48% of trans girls considered suicide within the past year, with 22% and 12% making an attempt. Rates were similar among nonbinary students.

It’s long been known that the risk of suicide falls back to normal rates when a trans child’s family is accepting, but fewer than one in three of students surveyed in 2022 said their home was affirming. Meanwhile, 51% of trans youth said their gender was affirmed at school; suicide rates were lower in such environments.

The wave of anti-LGBTQ legislation and violence of the last two years has increased rates of anxiety, depression and thoughts of self-harm for all LGBTQ kids, but especially for trans and nonbinary youth. Even when they do not attend schools where the new laws are in effect, 93% of trans youth say they fear they will lose their gender health care, 91% are afraid they will no longer be able to use the bathroom that matches their identity and 83% worry about gender-nonconforming students losing the ability to play sports, according to The Trevor Project.

These mental health issues make sports in particular important to LGBTQ youth well-being, says Caitlin Clark, a developmental psychologist and research director for GLSEN. “There is camaraderie, working together with peers, which you don’t often get in general in schools,” she says. “And there’s support from adults. On a sports team, you are often close to your coach.”

Because teams represent schools, Clark adds, there is an inherent sense of belonging. “Being on a team, the rest of the school is cheering for you,” she says. “We know it’s a space of positive youth development — and we know LGBTQ students don’t participate.”

The reality confronts the rhetoric

Organizations that promote and regulate student athletics have tried for years to make sports more inclusive. Most began loosening restrictions tying trans participation to hormone levels just as political rhetoric alleging harm to girls and women roared to fever pitch.

When the International Olympic Committee announced a year ago that it was ending trans inclusion policies based on athletes’ medical interventions and hormone levels, it handed authority over each individual game to that sport’s governing body, along with instructions to presume — pending rigorous research to the contrary — that trans athletes have no inherent advantage.

Citing the change to Olympics rules, and with little warning, in January the NCAA modified its own policies, delegating decisions on trans participation to the authorities overseeing different sports — but requiring trans athletes to undergo testosterone testing.

Some LGBTQ advocates clapped back immediately, accusing the organization of creating a workaround to take political pressure off leaders in states with both trans exclusion laws and sports-centric cultures. Previously, the NCAA had warned that it would not hold major — often lucrative — sporting events in places where all athletes were not welcome and safe.

What this means is that athletic organizations’ rules governing where and under what circumstances trans youth are allowed to play sports will remain a patchwork — fueling concerns among LGBTQ advocates that queer students will face increasingly hostile school climates. The state of the law, and state and federal interpretations of it, is confusing as well.

Guidance from federal officials has seesawed over the last six years. In 2016, the U.S. Education and Justice departments said Title IX’s prohibition on gender discrimination extended to gender identity, protecting trans students in schools and related educational facilities — including bathrooms and locker rooms — and programs such as sports.

In 2017, however, the Trump Education Department reversed course, saying such policies were best left up to local officials. On his first day in office, President Joe Biden ordered federal agencies to again protect trans and nonbinary youth.

Right now, 19 states, one territory and Washington, D.C., have laws prohibiting in-school discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. By contrast, 24 states offer no specific legal protection to LGBTQ youth, while Missouri and South Dakota have laws prohibiting schools and districts from enacting their own protective rules. Twenty-three states prohibit anti-LGBTQ bullying, while 23 do not.

Two states have unique legal landscapes. Iowa law protects students from in-school discrimination based on their gender identity, except in sports. In March, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed a law barring transgender girls and women from participation. In Virginia, although state law prohibits discrimination in schools on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, Gov. Glenn Youngkin in September ordered schools to restrict trans students to the bathrooms, locker rooms and sports teams matching the identity they were assigned at birth.

Such inconsistencies have led to a flurry of legal challenges throughout the country, many relying on different theories. The first of the suits, filed in Connecticut, claims that allowing trans students to compete on teams that match their gender identity violates cisgender girls’ rights under Title IX. In 2020, three high school girls represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom filed a federal lawsuit alleging that, absent their transgender competitors, the plaintiffs would have advanced to and won championships. The plaintiffs and the transgender opponents alike had mixed records of competing against each other and winning.

The lawsuit was dismissed in April 2021 on the procedural grounds that the two trans athletes in the original complaint had graduated and plaintiffs could not identify others. It is on appeal.

At the same time, Idaho became the first state to enact a wholesale ban on transgender athletes’ participation in sports. A trans woman who had previously been eligible to run competitively under NCAA rules sued. Concluding that there was no evidence girls’ and women’s sports were threatened by trans participation, a court halted enforcement of the law as the case moves forward.

Other students who have filed lawsuits in states with blanket bans include a Tennessee seventh grader who was not allowed to try out for a boys’ golf team and a 10-year-old Indianapolis girl who would be outed to her classmates if she is dropped from the softball team.

In Utah, where lawmakers overrode an emotional veto by Republican Gov. Spencer Cox to enact a ban, a court last summer halted enforcement pending further legal proceedings. The injunction was issued two days after the Utah High School Activities Association reported receiving complaints from parents asking officials to investigate the gender of their children’s competitors, arguing some of the girls “don’t look feminine enough.”

Even in places where discrimination for gender identity is explicitly prohibited, confusion created by proponents of the ban has led students to sue. One example: a trans boy swimmer in Minnesota whose school district made him use a segregated locker room despite state laws protecting his right to use facilities matching his gender identity.

Most of these lawsuits turn claims of harm on their head: not that bans are needed because participation by trans athletes could do potential harm to girls’ athletics, but rather that the bans do actual harm — to the trans athletes.

So what happens next?

One or more of the cases are likely to reach the U.S. Supreme Court, says Marie-Amélie George, an associate professor at Wake Forest University Law School specializing in LGBTQ rights. “They all get at the same issues, although via differing language and different laws and statutes,” she says. “They are all asking the courts to define what the language of Title IX means.”

Absent clarity on whether Title IX’s prohibition on discrimination on the basis of sex applies to sexual orientation and gender, the Biden administration and other proponents of LGBTQ inclusion have relied on a June 2020 Supreme Court decision, Bostock v. Clayton County, that found the ban on sex discrimination in employment in a different section of the same civil rights law, Title VII, extends to gender identity.

Accordingly, in July, the U.S. Department of Education released a proposed expansion of Title IX, extending the law’s protections against “sex-based” harassment and discrimination to gender-nonconforming students. The proposed rules — which interpret how the law should be upheld — did not address sports, something Biden administration officials are dealing with separately.

“What we’re seeing right now is that in every other situation, other than athletics, we have this proposed rule saying you can’t discriminate against an individual based on their gender identity or sexual orientation,” says Maya Satya Reddy, a clinical fellow at the Harvard Law School’s LGBTQ+ Advocacy Clinic. “And what we’re looking ahead to is this upcoming proposed rule that is specifically about gender identity and sexual orientation within athletics.”

The rule, she continued, would make it illegal for a school to enact a policy discriminating on the basis of gender identity.

In July, however, a Tennessee judge issued an injunction temporarily blocking the Biden administration from enforcing its Title IX rules in 20 states that sued the federal government over its interpretation of the law.

A ruling from the high court on any of the suits filed by trans and cisgender athletes would ultimately clarify whether the law protects LGBTQ students. Legal scholars note that while Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, authored Bostock, it’s unclear whether the court’s newer conservative jurists will agree with his reasoning that discrimination against sexual orientation and gender identity is clearly sex discrimination.

Pending legal clarity — and its impact on the culture of youth sports — LGBTQ students are likely to continue to face harassment and bullying on the playing field, advocates say.

“Trans athletes just want to play,” says Reddy. “They should have the same opportunities to play as cisgender women.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter