Experts: Dismal NAEP Scores Offer Districts Chance to ‘Pivot’ on Relief Funds

The push to spend additional funds on learning recovery comes as officials await federal answers on extension

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Most school districts adopted their budgets last spring, long before state and national test scores laid out the extent of pandemic declines, particularly in math.

That’s why some school finance experts are urging districts to redirect some of their plans for federal relief funds toward learning recovery before that money is actually spent.

“From our perspective, a pivot does seem warranted,” Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, said last week during a webinar. While it’s normal for districts to get assessment results after they’ve finalized their budgets, this year, she added, the achievement gaps are “more glaring.”

Her team’s analysis of National Assessment of Educational Progress data, released last month, showed that almost 2 million middle and high school students — who would have scored in the proficient range if the pandemic hadn’t occurred — are now below proficient.

And about 700,000 students “fell out of advanced level in math,” said Chad Aldeman, policy director at Edunomics. “This means 700,000 fewer future scientists, engineers, data and medical experts … that are now not in our pipeline.”

While district budgets include costs that are already “locked in,” such as salaries and signed contracts, Roza noted that districts still have some “wiggle room” to redirect funds toward more academic interventions if positions haven’t been filled. And when they’re negotiating contracts with afterschool providers they can require staff to spend time on math — or other areas where students have fallen far behind. Her comments followed a recent report from McKinsey & Company showing that districts have yet to spend $130 billion of the $190 billion in federal relief funds they received.

Amending an approved budget is not part of a district’s normal cycle, Roza said. But superintendents and school board members can request it. State education agencies can also require districts to report what they’re doing to address specific content areas, which might prompt a budget revision.

And while state lawmakers can’t tell districts how to spend relief funds, they can encourage or mandate districts to offer certain types of programs, like tutoring or summer school. Based on recent state test score trends, Austin Reid, senior legislative director for federal education policy at the National Conference of State Legislatures, said he expects to see similar actions when legislatures reconvene next year.

“I also think we may see more legislatures engaging in more oversight activities on [relief funds], which may include strong encouragement of certain strategies,” he said.

Chris Neale, assistant commissioner for federal relief programs at the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, said he’s seen several districts reopen their budgets after they’re finalized. While he doesn’t know the exact reasons, he said it’s “plausible” that assessment data is prompting the revisions. Other factors are likely, including “emergent needs for mental health services,” he said.

The ‘constraints’ on spending

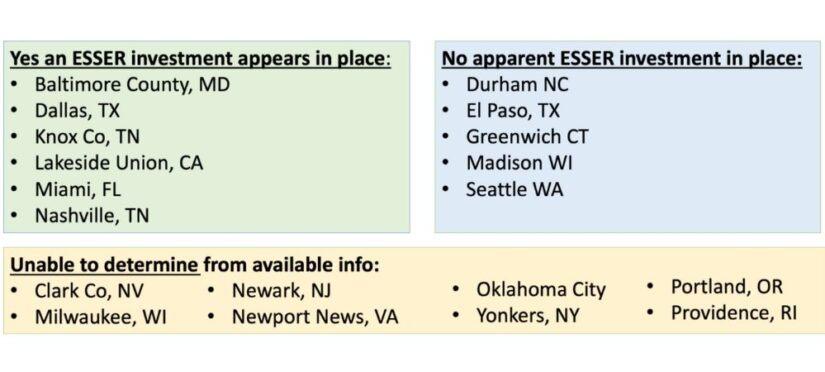

Using available financial data, Roza highlighted districts — including Baltimore County, Dallas and Miami — that are prioritizing math instruction.

A lot of districts are spending the one-time funds on teacher training — more than 80 of the top 100 districts, according to one analysis. In Oregon, for example, lawmakers and advocates urged districts to spend the funds on training teachers on elementary reading instruction, with the argument that it would have a long-term payoff. But Roza said professional development wouldn’t necessarily offer an immediate benefit to students.

The McKinsey report estimated that about $20 billion in relief funds might go unspent because of “administrative hurdles,” staff shortages and the inability of leaders to “orchestrate spending.”

Districts, meanwhile, are still waiting on the U.S. Department of Education to answer two questions: Will they have more time beyond the September 2024 deadline to fully obligate the billions of dollars in relief funds remaining from the American Rescue Plan? And are there additional “allowable uses” for relief funds that the department has yet to clarify?

“I have a lot of empathy for states and districts that are figuring out the best way to spend [relief funds] within the constraints they have,” said Sheara Kvaric, co-founder of Federal Education Group, a law firm specializing in federal education policy. “I think states and districts have innovative ideas, but it’s hard to commit to them without the assurance the spending is ok.”

Congress has joined education organizations in asking the department to allow districts to keep spending the money through the end of 2026, instead of January 2025. In a Nov. 10 letter, six House Democrats asked the department to issue guidance “given the crucial need to meet the immediate needs of students and to address the long-term impacts of the pandemic on academic growth and student mental health.”

Last week, the department also responded to a July letter from the AASA, The School Superintendents Association, with the same request. James Lane, senior adviser to Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, reminded the organization that 96% of the first round of relief funds from 2020 has been spent and that future extensions would be considered “under extraordinary, case-by-case circumstances.” He said an updated document on allowable uses would be coming soon.

Sasha Pudelski, AASA’s director of advocacy, said the letter wasn’t much of a response.

“It’s the same as before,” she said, “no answers, no process, no helpful information for districts and states.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter