Acknowledging Missteps, a Colorado District Chief Navigates ‘Devastating’ School Closures

With a combination of straight talk and a human touch, some say Tracy Dorland offers a roadmap for districts facing enrollment declines.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In April 2021, the board overseeing Colorado’s Jeffco Public Schools was about to hire Tracy Dorland as its new superintendent. But first, an urgent matter demanded their attention — closing Allendale Elementary School.

The district’s new chief thought spring was too late for such a drastic move: Parents had already made plans for the fall term.

“I thought, ‘Why are you closing a school right now? ’ ” Dorland said. “ We’re preparing for next year.”

Enrollment at Allendale, a school in Arvada, outside Denver, hovered around 100 students — representing a 45% drop since 2017. Some grade levels had dwindled to a single classroom and the district was losing money on basic services like busing and lunch. Most extracurricular programs had disappeared.

But closing schools was “political suicide,” Dorland thought.

Then she started visiting classrooms herself. “We had families deciding to leave these small schools even though they loved them,” she said.

Since her arrival, Jeffco has shuttered 16 schools. Four more are slated to close at the end of the school year.

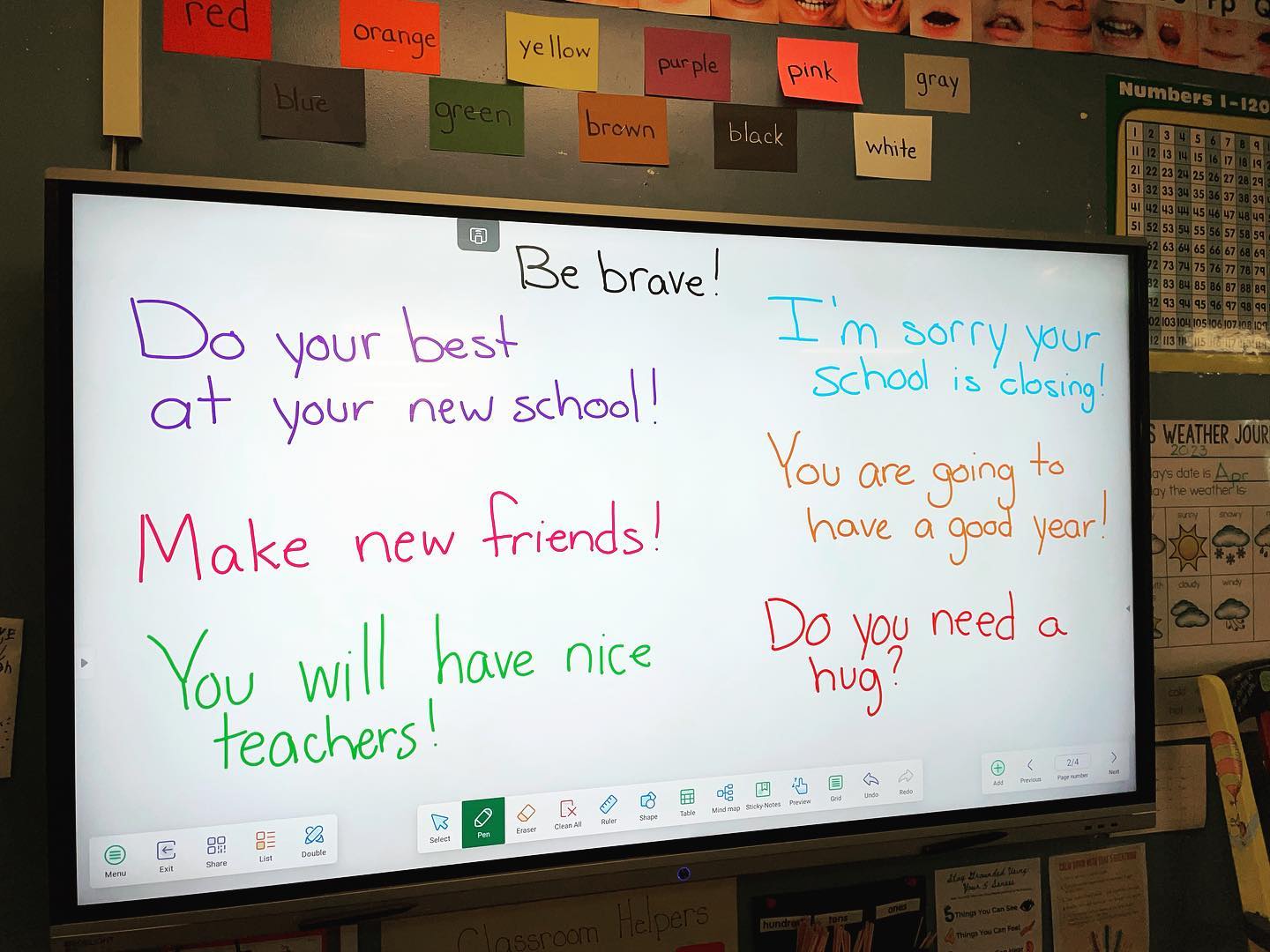

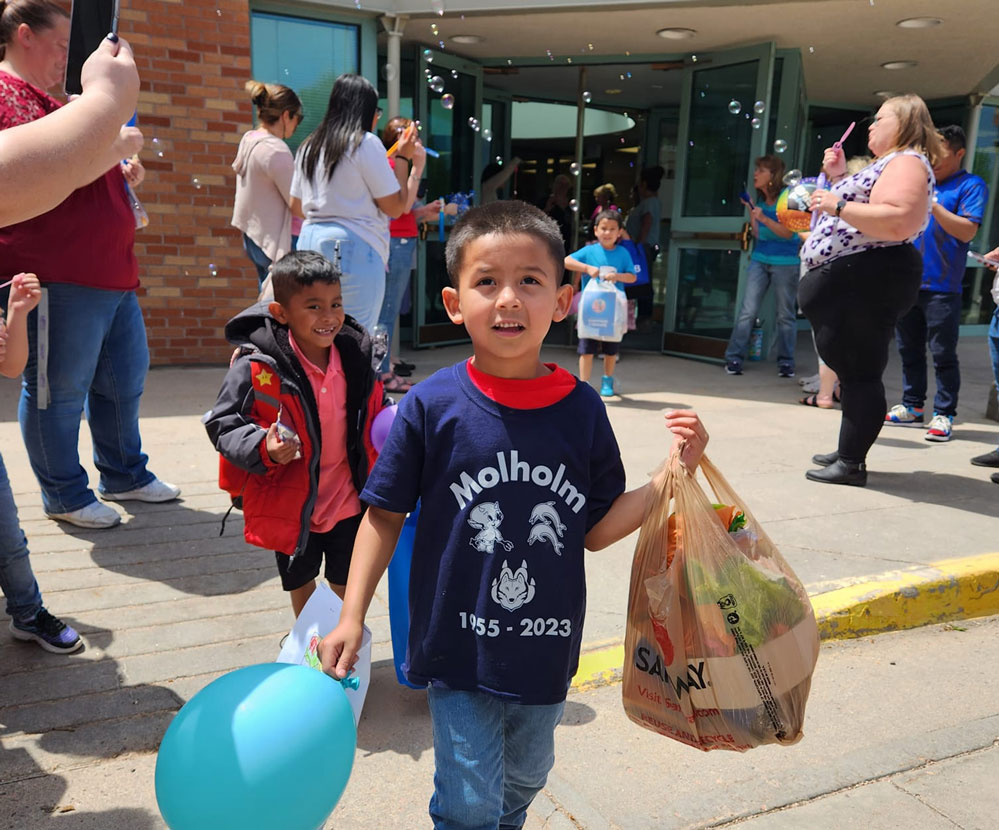

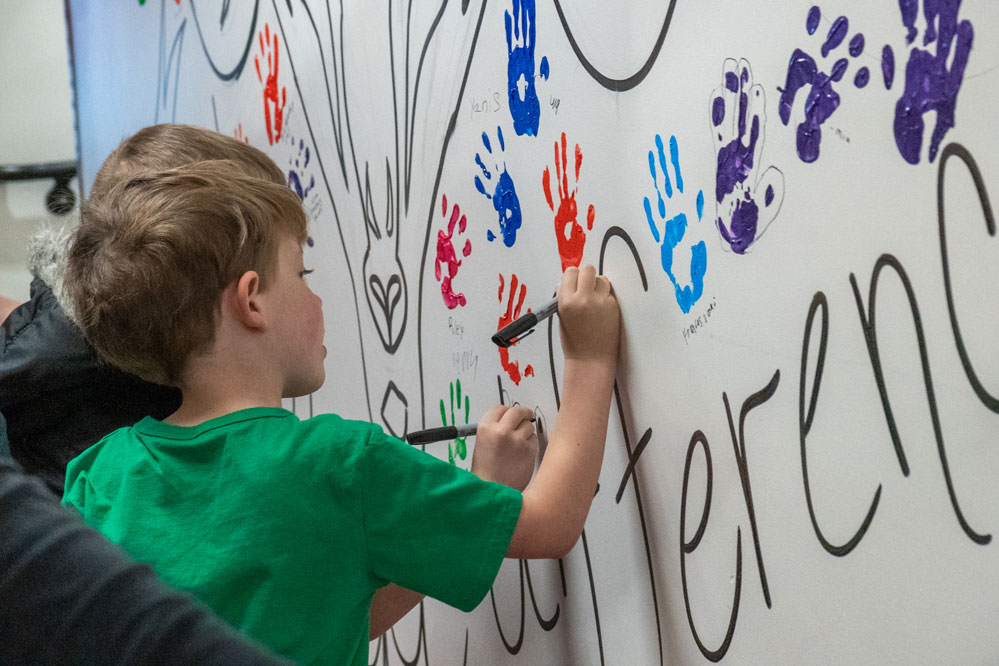

School communities forced to say goodbye to legacy institutions go through something akin to the stages of grief. Residents with emotional ties to schools their parents and grandparents attended frequently push back. But Dorland has earned respect for a straightforward approach to a process leaders across the country will confront in the coming years. While implementing a daunting closure plan, she didn’t ignore the human cost, assigning staff members to ease both principals and families through the transition.

“A lot of people don’t have that muscle — to just look someone in the eye and say, ‘I know this is devastating, but I’m looking at the district as a whole,’ ” said Trace Faust, senior project director at the Keystone Policy Center, a Colorado nonprofit that held community meetings to discuss the closures. “That’s a bold thing to do, and that’s what districts need right now.”

In Colorado, as in much of the nation, experts chalk up enrollment declines to a drop in birth rates and housing prices that remain out of reach for most young families. The “gateway to the Rockies” is such a desirable place to live that older residents often stay after their children grow up, leaving fewer houses on the market.

A need to grieve

At Fitzmorris Elementary, one first grade class had just five students. Small schools lacked their own music and physical education teachers. And afterschool providers canceled programs because only a handful of students signed up.

After a second last-minute vote to shut down Fitzmorris in the spring of 2022, board members decided they could no longer address closures piecemeal. The district recommended shutting down 16 schools and held a series of community meetings before casting a final, unanimous vote in November. The timing gave families the rest of the school year to absorb what the changes would mean for their children.

But some of those gatherings didn’t get off to a great start. With talk of “re-envisioning” schools and the benefits of consolidation, the staff from Keystone was several steps ahead of the community — even “tone deaf” to parents’ concerns, Dorland said.

Faust agreed those first meetings “honestly missed the mark. The community needed to grieve and needed to be mad.”

That’s when principals began to take a larger role in the conversations. School leaders could “get the room back together if things were going sideways,” Faust said. Some stationed themselves in their school libraries for days to talk to parents one on one.

What Dorland didn’t want, however, was parents coming to the forums hoping to get leaders to reconsider.

“I don’t believe in pretending like communities have a choice when they don’t,” she said.

‘Don’t want a mass exodus’

That left some parents feeling shut out. Families from Kullerstrand Elementary, a Title I school in the Jeffco city of Wheat Ridge, wrote letters and protested at public hearings.

“Their minds were already made up, which was really sad,” said Kim St. Martin, Kullerstand’s former PTA president.

After the board’s latest vote in October to close two K-8 schools this spring, some parents threatened to leave the district.

“That’s a tricky situation, because we don’t want a mass exodus,” said LaVerne Manzanares, a former reading specialist who now helps families with children attending new schools.

Michael Zweifel, a former principal whose school, New Classical Academy at Vivian, was one of those closed, also shifted to a new role. She began supporting administrators at “receiving” schools that suddenly had to accommodate more cars in their parking lots and students in the lunch line. They’ve opened up spots on school leadership committees for teachers from closing schools, and held ice cream socials, movie nights and picnics for families to meet.

The closures were especially jarring for families in Wheat Ridge, a tight-knit community between Denver and the Rockies. The district closed three of the small city’s elementary schools, sparking anxiety about the future of its local high school.

Alanna Ritchie, whose first grader attended Wilmore-Davis Elementary, was among several parents who wanted Wheat Ridge city council members to pressure district leaders to change their minds. During a September 2022 council meeting, she warned the mergers could lead to the opposite problem — overcrowding — and that some of the receiving schools couldn’t accommodate additional traffic.

The convenience of walking to school is a “right” that was being “ripped away from our own children,” she said. “Small, connected neighborhood schools — it’s what defines us as a true community.”

St. Martin, the former Kullerstrand PTA president, still gets choked up over losing her neighborhood school. It was important to her, she said, that her children attended a more racially diverse school. Now they attend predominantly white Prospect Valley Elementary.

“Selfishly, I loved my relationships,” she added. “You could talk to any teacher.”

‘Day and night contrast’

While some parents wish they could have had more say over which schools closed, experts say Dorland’s plan was better than leaving families in limbo. Brian Eschbacher, an enrollment consultant, said the uncompromising way she managed the closures is a “night and day contrast” to how Denver Public Schools, her previous employer, handled a similar issue.

Denver leaders hesitated to release a definitive list of schools to be closed last school year. They gathered input from the community, but ultimately abandoned a closure plan in the face of emotional appeals from parents.

Denver’s union-backed school board placed a lot of the blame for enrollment loss on charter schools. But Eschbacher, who previously led planning and enrollment services for the district, said the city has contributed to enrollment decline by continuing to approve construction of luxury high-rise apartments that don’t attract families with young children.

“I always tell boards, ‘This is outside of your control. This is about births and housing, and you don’t control either,’ ” he said.

Meanwhile, the challenges that defined Dorland’s early tenure aren’t over. Her plan to close two K-8 schools — Arvada and Coal Creek — has strong opponents, including Danielle Varda, the only person on the five-member board to vote against closure. She thinks the decision to shut down the two schools was rushed. Closing Arvada K-8 will cause further disruption for students who have been through previous mergers, she told the board. The district would also have to expand programs for English learners and immigrants at other schools when Arvada K-8 already offers those services.

“This plan perpetuates systemic oppression that these families have faced much of their lives,” she said.

Dorland acknowledges that parents in Wheat Ridge, where families have lived for generations, are “probably still angry.” She wishes she had done more to help city and county officials understand why the district couldn’t put off closing schools any longer. But once the decision was made, the consolidation process moved quickly.

“We had run out of runway,” she said, “and we had to take off.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter