Closing Time: San Antonio Supe Hopes Info Sharing, Help for Parents Can Ease School Shutdowns

Jaime Aquino counting on open communication on enrollment & funding to build trust, promises families kids are 'going to get an excellent education.'

By Beth Hawkins | August 21, 2023It’s not hard to find recent examples of places where broaching the need to close schools has blown up in district leaders’ faces. More than two decades of plummeting birth rates have hollowed out classrooms from coast to coast, yet board members and superintendents who propose a consolidation or shutdowns can easily find themselves out of a job.

As it became clear the pandemic was accelerating widespread enrollment declines, demographers, economists and school funding analysts started counseling that communication is key to winning buy-in from angry parents. Few education leaders heeded their advice, instead ducking the topic.

Now, school finance experts are watching to see whether things will go more smoothly in the San Antonio Independent School District, which last spring announced it will shutter a yet-unspecified number of schools at the end of the 2023-24 academic year. The district’s decision-making process, they say, appears to be unusually transparent.

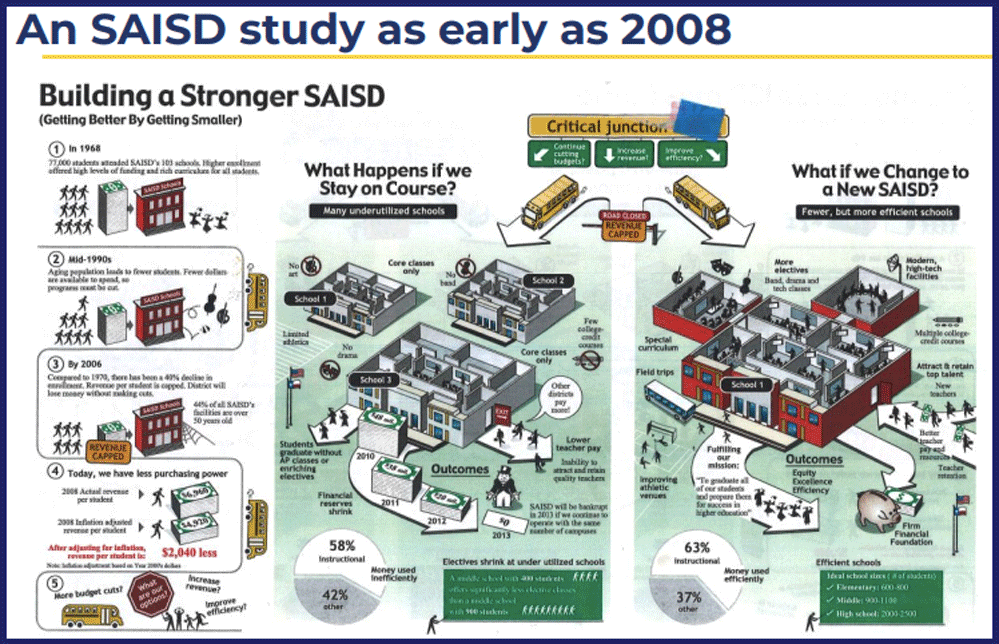

Describing the contraction as long overdue, San Antonio officials kicked off a presentation at the June school board meeting by showing a PowerPoint slide from 2008, making the case for confronting what was then 40 years of enrollment declines. At the top of the image, under the headline “Critical Junction,” two yellow school buses start down divergent paths: “Stay on Course” and “Change to a New SAISD.”

The same illustration could be used today. Over the last 15 years, enrollment has dropped from more than 55,000 students to less than 45,000. Twenty years ago, the district operated 106 schools. Now, it has 98, 35 of which have undergone some form of transformation in recent years.

Many reorganized around popular curricular themes, such as dual-language immersion, Montessori or gifted-and-talented academics. As a result, more than 2,200 students from other communities now attend SAISD schools, making it the most popular interdistrict-enrollment option in its Texas region.

But even with a boost from outside students, enrollment is expected to continue to decline over the next decade. The number of district residents under age 18 has fallen 14% since 2010, and births have declined 36% since 2007. Enrollment losses are likely to accelerate as older students graduate and there are too few kindergartners to make up for them.

Such seismic demographic shifts are taking place virtually everywhere. Between 2019 and 2023, public school enrollment nationwide fell by about 1 million, or 2%. Schools are projected to lose another 3 million students by 2029.

In most states, education funding is meted out according to enrollment, so even a small change to a student body has budgetary ripples. Adding to the pressure, many districts used their share of $188 billion in temporary federal pandemic relief to stave off what, amid fights over everything from face masks to teaching about race, was just one more explosive conversation.

“Most district leaders, in anticipation of angry backlash, just don’t raise the topic,” says Marguerite Roza, head of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab. “We’re seeing a lot of districts right now say, ‘Don’t worry, we’re not talking about school closure.’ And [leaders] thinking, ‘If I can just make it a few more months, then I’ll say it, because I don’t want to deal with it right now.’ ”

Postponing the painful conversation has financial consequences, she says, but also costs school systems time that leaders could have spent engaging the community about their priorities for a streamlined district.

“The public needs its opportunity to weigh in and marinate,” says Roza. “Not everybody’s going to be happy, but our experience is that when people have seen the trade-offs and the numbers, and they’ve had an opportunity to go back and forth, if it doesn’t have to be a situation where you’ve eroded trust in the leaders.”

In February 2022, Oakland, California, school board members voted to close 11 schools over two years. Protests and a hunger strike ensued, several sitting board members lost re-election and last January the board changed the plan to consolidate fewer buildings.

In St. Paul, where public outrage had stalled past consolidations, lame-duck officials scheduled a vote on long-postponed closures to occur during the short window between elections and the seating of new board members. The timing enabled the district to invest more of its federal COVID-19 recovery funds in academics than many districts.

Contentious discussions about closures have also played out in Denver, Los Angeles, Minneapolis and other shrinking districts. New Orleans, which has had a formal process for shutting underperforming schools for years, is struggling to determine how to shrink its all-charter school system.

Last fall, following a discussion about birth rates and how schools budget, the board of Colorado’s Jeffco Public Schools voted to shutter 16 elementary schools. In June, it followed with the consolidation of one middle and one high school into a single 6-12 facility. The process was emotional, but no one was ousted.

Newly installed as San Antonio’s superintendent, Jaime Aquino was watching. Last spring, he took a delegation from his district to Jeffco, and also arranged conversations with officials in Cleveland, which has scrambled to address population declines. Taking what they learned, and heeding the experts’ advice about communicating clearly and early, San Antonio officials drew up a plan focused not on a budget crisis, but on the need for equity within the district.

“We are not right-sizing because we’re approaching a fiscal cliff,” says Aquino. “We’re doing this because we need to deliver on the promise that we make to our students and our families that no matter where they attend [school], they’re going to get an excellent education.”

Right now, the district’s larger schools subsidize their underenrolled neighbors — which still can’t afford a full array of basic academics and extracurricular activities.

Operating an elementary school with 644 students costs $6,888 per child, according to a district analysis, compared with $16,261 where there are 109 students. Despite the higher per-pupil funding, some of the undersubscribed schools can’t pay for math and reading teachers with expertise in each grade, mental health workers and extracurriculars.

Particularly in early grades, it’s harder for teachers who have students from more than one grade to deliver instruction. And even where educators can focus on one age group, not having colleagues with whom to share strategies can pose problems. Meeting the needs of students still learning English or with disabilities is harder with a small staff.

Aquino started talking about the need for a district contraction in spring 2022, when he was appointed superintendent, describing the excess capacity as a barrier to equity.

More recently, district leaders shared information on how many students schools are drawing from their assigned neighborhoods and other parts of the district, as well as how many children from those communities are enrolled elsewhere, either in a San Antonio ISD school or one outside the district. The presentation is dramatic.

S.H. Gates Elementary, for example, is at 25% of capacity, built for 615 students but serving 156. Meanwhile, 202 students who live in its attendance zone attend schools elsewhere in the district. Approximately one-fourth of its third- through sixth-graders were reading and performing math at grade level at the end of the 2021-22 school year.

Meanwhile, Bonham Academy has 599 pupils — 13 more than its official capacity. Four hundred of those students live outside its assigned residential area, while 114 neighborhood kids either attend non-district schools or programs in other zones.

Bonham does not outperform Gates in math, but its pupils read at grade level at twice the rate. It is a dual-language immersion school, an especially popular model in a majority-Latino city.

Advanced Learning Academy, one of several magnet schools created as a part of a district’s 2018 academic reorganization, has space for 927 students but enrolls 1,047. At Douglass Elementary, half of the 385 kids come from the surrounding neighborhood, which sends an equal number to outside schools.

To Roza, these numbers underscore an important and frequently misunderstood element of closure discussions: People typically protest shuttering any school, even if its poor performance means they won’t send their own children there.

“Communities will just react so negatively, like it’s a punishment that you’re closing us because we were doing poorly,” she says. “But the truth is that parents already do that when they have a choice. What we tend to see is that the underenrolled schools aren’t the higher-performing ones.”

In addition to enrollment, capacity and cost per pupil, the “right-sizing” criteria detailed on the district’s website include academic performance, investments in buildings and partnerships with local industry, colleges and other organizations. No school will close until it can be determined — using the same criteria — where its displaced students can be accommodated.

Partly because he anticipates better distributing the district’s existing staff and allowing its educator corp to shrink through attrition, the superintendent doesn’t anticipate large-scale layoffs.

On Sept. 18, SAISD leaders will present the school board with a proposed list of schools for closure or consolidation. In the six weeks that follow, the district will hold a series of community meetings about the initial recommendations, with a particular focus on where, if the changes are implemented, students would end up and how they would progress from elementary to secondary school.

On Nov. 13, the board will vote on final recommendations as a package — which means it will not make exceptions for individual schools. Because this will be complicated by the need to accommodate English learners, students in dual-language programs and other children receiving unique services, each school to be closed will be assigned an enrollment specialist to help families with placement.

Will the process go more smoothly than in other places, or touch off the kind of political churn that has led some districts to back off of closures in the face of community anger? The executive director of the San Antonio parent advocacy group MindshiftED, Maribel Gardea, says the process so far seems very different from poorly led closure conversations in neighboring districts.

“It looks like they are trying to be as transparent as possible at the forefront,” she says. “But parents are just kind of waiting for a list of possible schools that will close.”

Announcing up front that the board will vote on the entire list, and not bow to pressure about any given schools, is smart, says Gardea. She is less convinced that the contraction will boost academic achievement at the low-performing schools that remain open but have not received the same district investment as the ones reorganized in recent years.

Board Chair Cristina Martinez is more optimistic. “This is a real opportunity to really help families find a school that’s going to meet the needs of all of their children, because none of our schools are the same,” she says. “It’s also an opportunity to make sure those students who might not have been receiving some offerings really do have those options now.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter