WATCH: Education Experts Talk Student Literacy, COVID Learning Loss and How Teachers Can Confront the Widening Achievement Gap

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

How hard can it be to teach kids how to read?

Well, if you ask Mary Clayman, it’s the equivalent of rocket science. “We cannot put any curriculum in front of a teacher and expect them to become a master of their craft,” said Clayman, Director of the DC Reading Clinic.

“There is a huge body of knowledge that teachers need to have access to and to understand to be able to adequately diagnose and intervene with a student.”

In her role at the reading clinic, Clayman trains teachers in the science of reading, which she defines as “this vast body of knowledge, decades of research, fMRI studies, which is cognitive science, information on the English language, [and] the theoretical underpinnings of how we think children acquire print.”

But that leads to a big question for education leaders: “Is the instruction in schools informed by this vast body of knowledge?”

If this video isn’t playing, click here to watch.

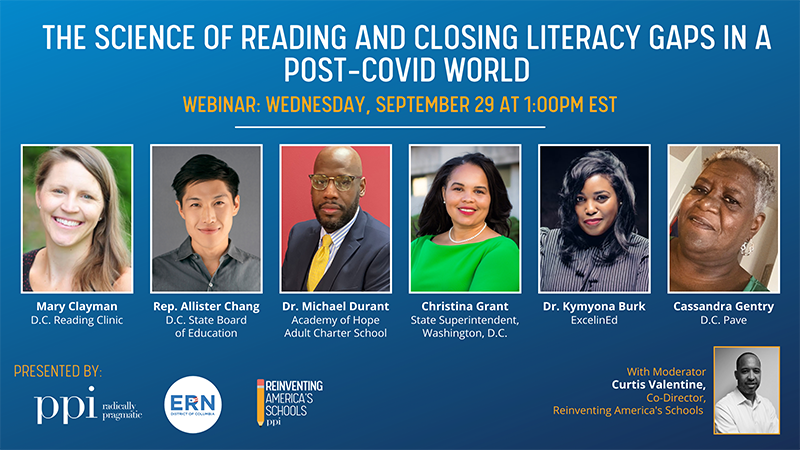

Clayman was among a panel of experts assembled by the Progressive Policy Institute and The 74 on Wednesday to deal with the enormous question of how educators will close the achievement gap in literacy that has grown to a chasm during the COVID-19 pandemic. The panel was also sponsored by Education Reform Now DC.

Dr. Kymyona Burk, Policy Director for Early Education at the policy and research group, ExcelinEd, laid out the challenge that educators face. Even before the chaos and disruption of the pandemic, only about 35 percent of the nation’s 4th-graders were scoring as proficient in reading. But that number doesn’t tell the full story, she said.

“We can no longer mask how our states are performing by how well our white students are performing,” said Dr. Burk. If you look at a racial breakdown of those reading scores, 45 percent of white students are scored as proficient, while only 18 percent of Black students and 23 percent of Hispanic students.

“Whether we call it learning loss, interrupted learning, unfinished learning, all of these terms, our proficiency rates in English declined but what’s also very eye-opening, for math, it decreased even more.” In some states, the pandemic decline in reading proficiency has been measured at 3 percent, in others at 12 percent.

“Students who are not proficient readers turn into adults who are not proficient readers,” Dr. Burk said.

Cassandra Gentry, a parent leader with the group Parents Amplifying Voices in Education in Washington D.C., spoke from experience about the plight of students who lost so much learning time during the pandemic.

Gentry said she was the guardian of a 5th-grader who wasn’t proficient in reading last year, “and after 19 months, she has really lost a lot more.” The young girl did not attend kindergarten or 1st grade, “so she did not learn the basic fundamentals that she needed in order to be proficient. She’s still struggling because of that.”

“So one of the things that I noticed about the science of reading is that early childhood intervention is so important.”

Gentry also noted the importance of getting reading programs in all schools, not just a select group of them. “We need equity,” she said. My school doesn’t have reading clinics; they don’t have reading partners.”

“Our children of color and our Hispanic children are in need of these resources also,” Gentry added. “This science of reading is going to have to be equitable.”

The panelists offered a variety of ideas about how to improve literacy for students … and adults. Allister Chang, a member of the D.C. State Board of Education, said he has “extended literacy programs to spaces like barber shops and laundromats and to weave literacy programs into the daily rituals of people’s lives.”

“That’s where I’ve seen the greatest impact.”

Chang also urged that education leaders learn from health care decision makers. “They’re currently investing more and more in what they call the social determinants of health,” he said. “In 2018 Kaiser Permanente invested $200 million to take on housing instability, knowing that the investment would actually reduce their health care costs downstream.”

He added: “Let’s advocate for similar funding to be invested in what we can call the social determinants of education.”

Dr. Burk called for states to use the huge influx of federal money from President Biden’s American Rescue Plan to “invest in people.”

“Invest in your teachers; build their knowledge,” she said. “Empower your teachers to stand in front of children every day and know that they are skilled enough to address the different needs, the different proficiencies and challenges that students bring into those classrooms.”

Dr. Michael Durant, chief academic officer of the Academy of Hope Adult Charter School in Washington, D.C., said it’s important to deal with other social challenges that “people have to battle before they even set foot into a classroom.”

“We’re dealing with homelessness; we’re dealing with food disparities; we’re dealing with lack of transportation; we’re also dealing with child-care issues,” he said. “All of those resources are needed, especially when you want a person to be able to be committed to education.”

Dr. Christina Grant, Acting State Superintendent of Education in Washington, perhaps put it mostly directly.

“Our country is only as good as our most literate person,” she said. “We have to make sure that our resources and our priorities are all in alignment of ensuring that our children are learning and are being taught in the best ways to make them love reading.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter