Bible-Infused Curriculum Sparks Texas-Sized Controversy Over Christianity in the Classroom

Responding to concerns about religious bias, state education officials say they will add material on the First Amendment.

The day before he unveiled a massive new elementary school reading program laden with Bible stories, Texas education Commissioner Mike Morath sat down with a Democratic lawmaker at the state capitol.

Rep. James Talarico had concerns.

The third-term legislator from Round Rock, near Austin, pointed Morath to a lesson on the Sermon on the Mount — Jesus’s instruction to “do unto others as you would have done unto you.”

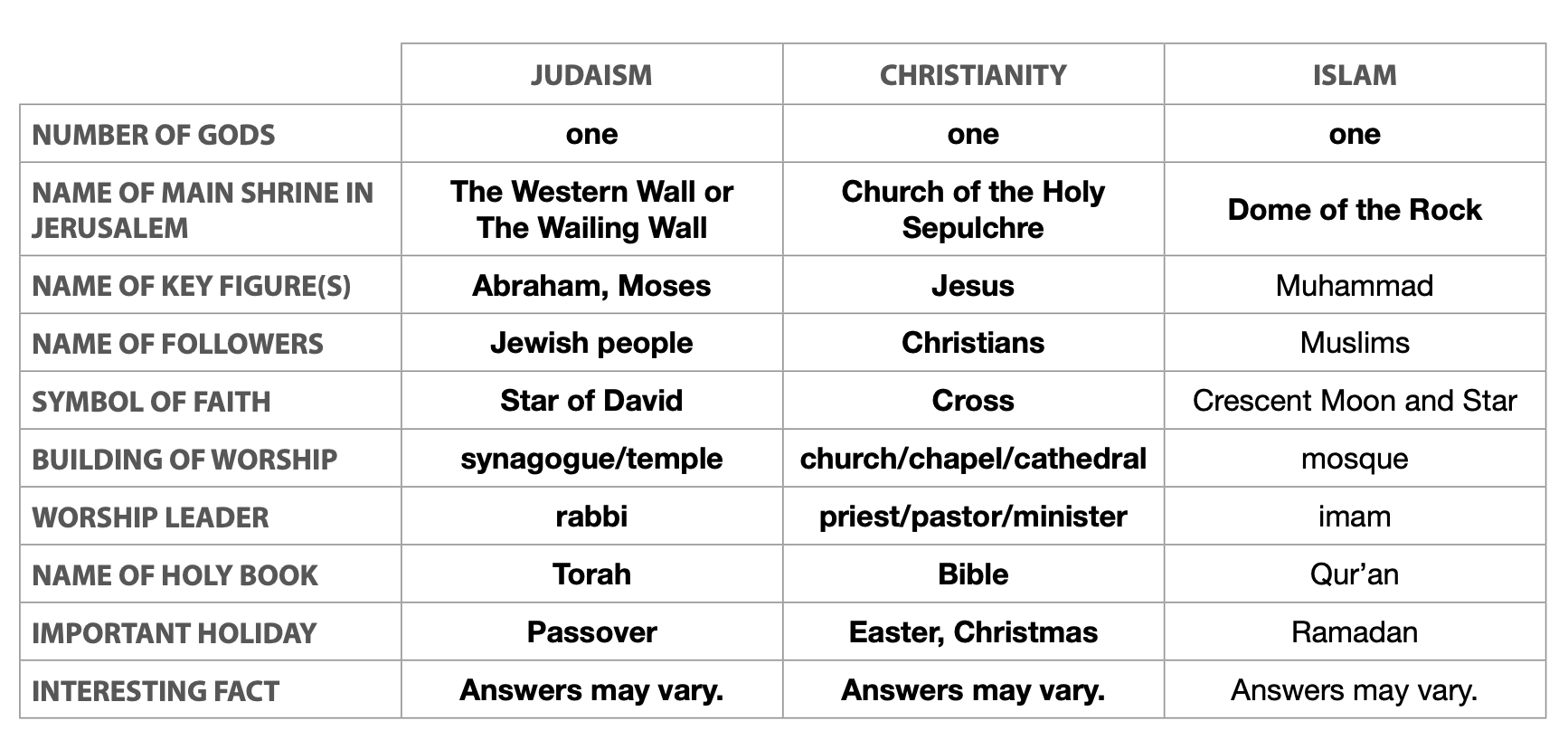

The text makes only passing reference to similar messages in Islam and Hinduism, and never mentions that Buddha taught a version of the Golden Rule 600 years earlier.

“I think it’s pretty egregious and will shock a lot of Texans,” Talarico said of the curriculum.

If it seems strange that four paragraphs about an ancient text in a lesson for kindergartners arouses such passions, welcome to the latest Texas-sized controversy about Christianity in the classroom.

Talarico is not just a Democrat in a deeply red state, but a former middle school English teacher and a seminary student studying to be a Presbyterian minister. Morath, he said, agreed the new material doesn’t grant “equal time“ to other religions. “I thought that was a fundamental flaw in this curriculum. He did not.”

As parents, academics and activists begin to pore over the thousands of pages the education department released, Morath’s acknowledgement sheds light on the state’s approach.

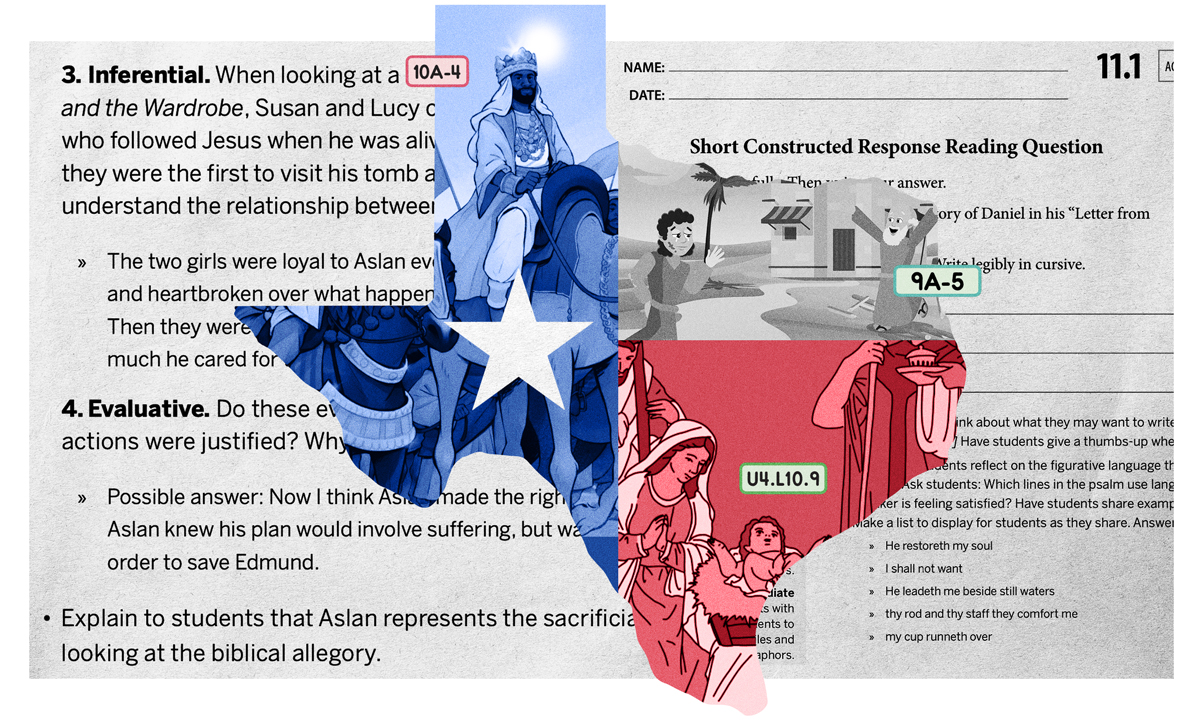

The new curriculum is based on the increasingly popular notion of “classical education,” which stresses the primacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition in shaping Western literature and U.S. history. As The 74 first reported last week, the project won praise from conservatives and parents who want students to get more rigorous reading material. Connecting coursework to ancient texts, including the Bible, offers students a cultural vocabulary they’ll need to tackle more complex assignments in middle and high school, Morath said.

He downplayed the religious material as a “small piece” of the curriculum, and called the biblical lessons ”a tiny fraction of the overall fraction.”

But a review by The 74 shows that biblical figures and stories are central to multiple lessons across the 62 K-5 units. The curriculum not only gives short shrift to other religions — Muhammad appears to have escaped mention, despite his role in shaping a faith practiced by half a million Texans — but scholars who have examined the material say it offers a decidedly Christian interpretation of history, particularly the story of America’s founding and civil rights struggles.

A textual guide for a third-grade unit on ancient Rome recommends teachers play “Silent Night” or “Away in the Manger” as they begin a lesson on the life of Jesus — from his birth and ministry to Crucifixion and Resurrection. In addition to a smattering of New Testament vocabulary (“messiah,” “disciple”) students get what appears to be a factual account from Josephus, a first century historian, on Christ’s death: Jesus’s disciples reported that he “appeared to them three days after his crucifixion and that he was alive.”

But scholars overwhelmingly reject the authenticity of this account, which they say was likely added by medieval clerics more than a thousand years later in an attempt to prove Christ’s deity.

“To use this as historical proof, which is exactly how it is presented in this lesson, is quite unwarranted and specious,” said L. Michael White, a biblical scholar at the University of Texas-Austin.

In keeping with classical education’s focus on religious allusions, that lesson sets the stage for a fifth grade study of C.S. Lewis’s “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.” The celebrated fantasy tells the story of four siblings who evacuate to the English countryside during World War II. They emerge through a magical armoire to encounter Aslan, a noble lion who later sacrifices himself for one of the children and returns from the dead.

The teacher’s guide calls it a “biblical allegory.”

“Explain how the Old Testament of the Bible had many prophecies about a future savior that are written as fulfilled in the New Testament by Jesus,” the note says. “There are also prophecies in the New Testament by Jesus. There are prophecies in the Bible about a future where Jesus returns to the world to make wrong right.”

Those instructions alarm one prominent education figure. In the early 1990s, Sandy Kress helped develop an accountability system for Texas schools that inspired No Child Left Behind, the landmark federal education law. Kress, who is Jewish, later advised George W. Bush when the former governor became president.

“I would argue this is teaching Christianity,” said Kress. His school reform days behind him, Kress now teaches and funds projects that encourage interfaith conversations between Christians and Jews.

Morath’s staff called on Kress for guidance on the curriculum last year, and on his advice, recruited his rabbi to review earlier drafts of the material. Kress told The 74 that he wants further revisions and is hopeful the state will consider them.

“Can Christians do this in a way that is respectful of other faiths … without feeling the need to prove Christian doctrine? That’s the test for them,” Kress said. “Whether they pass the test or not will prove whether this is an honorable exercise and whether it would be able to survive a constitutional challenge.”

State officials declined to comment on their dealings with Kress and Talarico. In a statement, Morath said the biblical material in the curriculum “does not include religious lessons as one would find in a religious school.” He added that the content reflects “various religious traditions” and that “students will learn about aspects of most major world religions.”

But in response to criticism, education officials promised to add “language from the First Amendment” on the need for a clear separation between church and state to its lessons on American history.

The public has until Aug. 16 to comment on the proposed curriculum, which goes to the state Board of Education for approval in November. The stakes are high. If adopted, the curriculum would instantly become not only the nation’s largest classical education model, but the biggest infusion of Judeo-Christian teachings into the public education system in decades. The state is encouraging districts to adopt the material by offering incentives of up to $60 per student.

To Morath, the new curriculum offers schools their best chance at raising reading scores in a state that saw sharp declines during the pandemic. In addition to phonics-based instruction in the early grades, the curriculum draws from history, science and the arts to boost students’ knowledge of the world. While the biblical material has drawn the most attention, there are many units that have no religious references and highlight famous Texans, like civil rights leader Héctor García and Black-Native American aviator Bessie Coleman. Students learn best, Morath said, when they get early and repeated exposure to a subject.

“When you’re designing elementary reading materials, you have to pick topics and stick with them for a few weeks,” he told The 74. In districts that have piloted some of the material over the past three years, “the vocabulary complexity is night and day different” than some of the more simplistic reading lessons teachers used before, he said.

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush congratulated Texas on offering districts “rich content based on the science of reading and not outdated practices,” while conservative lawmakers and classical education advocates brushed off concerns that the materials have too many biblical references.

The Texas curriculum “strikes me as a rather mild step in the right direction,” said John Peterson, a humanities professor at the University of Dallas. For years, he said, “anything passingly biblical [has been] treated as a form of pornography, something filthy and shameful, and only to be consumed in private.”

‘Zero reference points’

Jeremy Tate knows firsthand how difficult it can be to engage students who lack a basic knowledge of the Bible. When he taught Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales to 10th graders in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, they had “zero reference points” for the collection of stories told by medieval pilgrims on their way to Canterbury Cathedral.

Some students didn’t have any knowledge of the Bible, let alone “anything about a pilgrimage, a relic or any of the language that was so much a part of the vernacular,” said Tate, now CEO of the Classical Learning Test, an alternative college entrance exam.

He’s concerned, however, about the classical movement being “politically hijacked” by Republicans trying to appeal to conservative Christians.

“In some ways, it’s an impossible battle,” he said. “We’re living through a moment where very few people can think outside of political categories.”

As if to underscore that point, the new curriculum arrived just four days after the state’s Republican party unified behind a platform calling for mandatory “instruction on the Bible, servant leadership, and Christian self-governance.” Delegates also want students to study an 1802 letter from Thomas Jefferson that Christian conservatives use to argue that church-state separation is a myth.

‘Cultural heritage’

That approach contrasts with Morath’s more measured admonitions to those who reviewed the materials. The commissioner’s charge to a 10-member advisory board at their first meeting last summer was to “make sure we were on the side of literature as opposed to a worshipful treatment of that material,” said Marvin McNeese Jr., an adviser who teaches at the College of Biblical Studies in Houston, an orthodox school that he said takes a “traditional interpretation of the Bible.”

All the stories that I read directly explain something that students may very well come across. I mean, we have laws named Good Samaritan laws.

Marvin McNeese Jr., College of Biblical Studies

The volunteers included some recognizable names, like former GOP presidential candidate Dr. Ben Carson, who served as a cabinet member during the Trump administration, and Danica McKellar, an actress and mathematician who has been outspoken about her Christian faith.

McNeese said he spent about 40 hours between August and February reviewing lessons and doesn’t see a problem with its Judeo-Christian emphasis.

“It’s because of our own cultural heritage,” he said. “All the stories that I read directly explain something that students may very well come across. I mean, we have laws named Good Samaritan laws.”

Under federal law, schools can teach the Bible as literature, but not in a devotional way. Mandatory Bible readings and prayer were common in many public schools until a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions in the early 1960s ended those practices. The court, however, allows voluntary prayer and under its current conservative majority has increasingly tilted in favor of religious expression.

Conflicts about biblical material in public school have recently erupted over Bible verses in a Florida financial literacy textbook and in an Oklahoma middle school that posted a New Testament verse on a hallway wall. But experts say the scope of Texas’s undertaking increases the potential for trouble.

The Bible references in the new curriculum start in kindergarten, when children draw pictures inspired by the creation story in the Book of Genesis. By fifth grade, students studying poetry ponder what King David meant in Psalm 23 when he wrote, “The Lord is my shepherd.” In between are familiar Bible stories about the wisdom of King Solomon, the prodigal son and Paul’s conversion to Christianity on the road to Damascus.

The Texas lessons frequently say “according to the Bible” or “as the Bible explains,” but Mark Chancey, a religious studies professor at Southern Methodist University, dismissed those as “meager efforts” at objectivity. “The literalistic way they present Bible stories encourages very young children to simply take them at face value,” he said.

He pointed to a fifth grade lesson on Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” in which teachers read a passage from the Book of Matthew for added context. Students, he said, are bound to be left with questions.

“How did Jesus know someone would betray him? What does Jesus mean when [the teacher] says the bread is his body and the cup is his blood?” Chancey asked. “Is the teacher ready to explain all the different versions of Eucharistic theology found in different forms of Christianity?”

The literalistic way they present Bible stories encourages very young children to simply take them at face value.

Mark Chancey, Southern Methodist University

Many of those teachers have probably never received training on how to discuss religion in a public school classroom, said Katie Soules, founder and director of the Religion and Education Collaborative, which focuses on how schools talk about matters of faith. Teachers might be better off focusing on the literary value of Lewis’s “Chronicles of Narnia” than prompting students to think Aslan, the lion, represents Jesus, she said. Teachers could “very quickly end up in violation of the First Amendment.”

The tone and focus is a concerted departure from the curriculum Amplify, a leading publisher, offered the state in 2020 under a $19 million contract. In over 40 pages, that version gives equal weight to Christianity, Islam and Judaism. A separate unit features lessons on Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

The state, however, rejected those sections, said Amplify officials, who later balked when Texas asked for additional biblical content. As The 74 previously reported, the company opted not to bid on a contract for the next phase of the project.

Experts say the current curriculum is notable not only for its emphasis on Christianity, but for what it omits.

A first grade lesson on American independence, Chancey said, paints an idealistic picture of religious liberty by asserting different denominations “thrived in the colonies.” In reality, pilgrims were often intolerant of those who believed differently.

The program devotes ample space to the evangelism of the colonists during a period of religious revival known as the Great Awakening. But The 74’s review found no material on the considerable influence of thinkers from the Enlightenment, a concurrent intellectual movement that inspired the writings of early American thinkers on individual rights and church-state separation.

‘Both sides of that debate’

That stained glass lens extends to the Civil Rights era. In both second and fifth grade, the text emphasizes the Christian faith of Black leaders as key to the movement to end segregation. But there’s no mention of faith leaders who used the Bible to justify racism and Jim Crow laws, like Henry Lyon Jr., who preached that God “started separation of the races.”

“If you just portray that religious leaders were against segregation, that’s extremely misleading,” Chancey said. “You had religious leaders on both sides of that debate.”

An assignment on “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” points fifth graders to Martin Luther King Jr.’s biblical allusions, including the persecution of early Christians and Jews who refused to worship false idols. But it ignores King’s intended audience — “white moderate” preachers “who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation.”

“Dr. King’s focus was the incompatibility of racial segregation with Judeo-Christian values and the Christian faith,” said Raymond Pierce, president and CEO of the Southern Education Foundation, a nonprofit focused on equity.

Pierce has a divinity degree, leads a Sunday school class and teaches political theology at Duke University. His family tree extends back through the founding of the Black Pentecostal Church in the early 1900s. “It does not get much more fundamental than that,” he quipped.

But he’s also a civil rights attorney. In reviewing excerpts from the curriculum for The 74, Pierce found himself turning to James Madison’s cautionary words to Virginia lawmakers in 1785. Madison wrote that while Christians fought for their own religious liberty, they could not “deny an equal freedom to those whose minds have not yet yielded to the evidence which has convinced us.”

Those who support the Texas curriculum are “pushing a warped version of Judeo-Christian principles,” Pierce said. “It is quite troubling that these supporters either intentionally or naively want to bring divisive issues within the Christian Church into our public schools.”

To share tips on Texas’s proposed reading curriculum, contact Linda Jacobson at lrjacobson@proton.me.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter