Cardona’s Tutoring Charge, 1 Year Later: Some Progress, but Obstacles Remain

The education secretary told districts to offer struggling students 90 minutes of tutoring each week. Here’s what happened

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

One year ago, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona issued a charge to schools still reeling from months of remote instruction during the pandemic: Students who fell behind should receive at least 90 minutes of tutoring each week.

His speech on Jan. 27, 2022, “likely produced a lot of head-nodding,” said Susan Enfield, superintendent of the Washoe County district in Nevada, who caught the live stream that day. Even then, she knew it would be a hard prescription to fill. Students needed one-on-one or small group attention, but there weren’t enough tutors to go around.

“The need was so vast,” she said.

On Tuesday, Cardona is set to revisit his administration’s priorities in a speech titled “Raise the Bar: Lead the World.” But nearly three years after the pandemic began, the need remains great, if recent test results are any indication. Despite some promising results, school districts hoping to scale up their tutoring efforts are running up against some persistent obstacles.

Cardona’s 2022 speech was a “good use of the bully pulpit,” said Phyllis Jordan, associate director at Georgetown University’s FutureEd think tank. “But it couldn’t overcome the implementation problems school districts had — from finding tutors to signing contracts to getting students and families to commit the time.”

The tight labor market and halting response from families meant districts often served fewer students and offered a fraction of the tutoring hours they’d originally planned, according to a December study from CALDER, a research center. For example, one district that set out to offer students 90 sessions throughout the school year ended up giving them an average of 13.

Those who received tutoring weren’t always the ones who needed the most help, and some districts’ efforts faced months of delays due to lengthy contract negotiations with outside providers.

Even now, some parents can’t get tutoring for their children when they need it — parents like Tamara Miles of Nashville, whose 9-year-old daughter Faith risks repeating third grade because she’s so far behind in reading.

Her school, Westmeade Elementary, participates in a district tutoring program that currently serves 3,100 students. But district spokesman Sean Braisted said it’s not an “open enrollment” program — students are selected by teachers and administrators based on test scores.

Those not chosen, like Faith, can participate in a summer program or receive tutoring next year, he said.

But Miles fears that will be too late. “She’s lost so much confidence in herself,” she said.

Rebuilding students’ self-esteem requires ongoing support from the same tutor, said Susanna Loeb, an education researcher at Stanford University. Those relationships, she said, allow students to take risks and work until they understand the material.

In the year since Cardona’s address, she said she’s seen real improvement in some district’s ability “to actually pull off harder, more intensive support for students.”

That’s partly due to her previous work at Brown University on the National Student Support Accelerator. The center summarizes important research about high-dosage tutoring — likely the inspiration, Loeb said, for Cardona’s prescription for “30 minutes per day, three days a week, with a well-trained tutor.”

The National Partnership for Student Success — which the Biden administration launched last July — is another attempt to connect schools and families with organizations and individuals willing to put in that kind of time.

The team offers advice to states and districts and runs a website that fields requests from potential tutors and mentors. Next month, Robert Balfanz, the Johns Hopkins education professor leading the effort, plans to provide further updates on work to connect districts to volunteers.

The education department did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Way ahead’

Colleges and universities are especially valuable sources of tutors, Loeb said, pointing to efforts in the Guilford County, North Carolina, schools. Working with three local universities, the district has built a tutoring corps of 670 undergraduate and graduate students.

“We were way ahead,” Jusmar Maness, the district’s chief academic officer, said about Cardona’s speech. She credited former Superintendent Sharon Contreras with implementing the high-dosage model during the 2020-21 school year. “We saw an immediate demand. Our challenge was trying to find the team to manage the speed with which the program has grown.”

To finance its efforts, officials combined federal relief funds with a $2 million grant earmarked in the federal budget for the program, thanks to U.S. Rep. Kathy Manning. The district pays the undergrads $25 an hour and covers an average of over $40,000 in tuition and fees for the graduate students. They receive training and “almost become staff members of the schools,” Maness said.

Like the students they help, many of the tutors are Black and Hispanic, so kids “see themselves reflected in higher education,” she said. And the majority of the college students are not in teacher preparation programs, so they “expose students to majors that local universities offer.”

Encouraging in-classroom use

Meeting with the same tutor over time — as students do in Guilford — especially benefits students in the elementary grades, research shows.

But many districts also spend relief funds on virtual, around-the-clock homework help. One service, Tutor.com — affiliated with test prep company Princeton Review — provided almost 2 million tutoring sessions in 2022, according to CEO Joshua Park.

The platforms tend to benefit students who are “self-motivated and bring their own questions,” Loeb said. Washoe County has a contract with Paper, another on-demand service that Enfield said is ideal for older students.

“The way high schoolers’ body clocks work,” she said, “they’re doing their calculus homework at 11:30 at night.”

But such programs don’t deliver the same results as in-person, high-dosage tutoring, which Loeb said is the “only way that we really know how to re-engage students and help them catch up if they are way behind on learning.”

The Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia released data in October showing that when Tutor.com first became available, few students logged on.

And last year, most students used it for less than an hour — an “amount of time that is unlikely to yield tangible benefits to student achievement, particularly for those with greater academic need,” the report said.

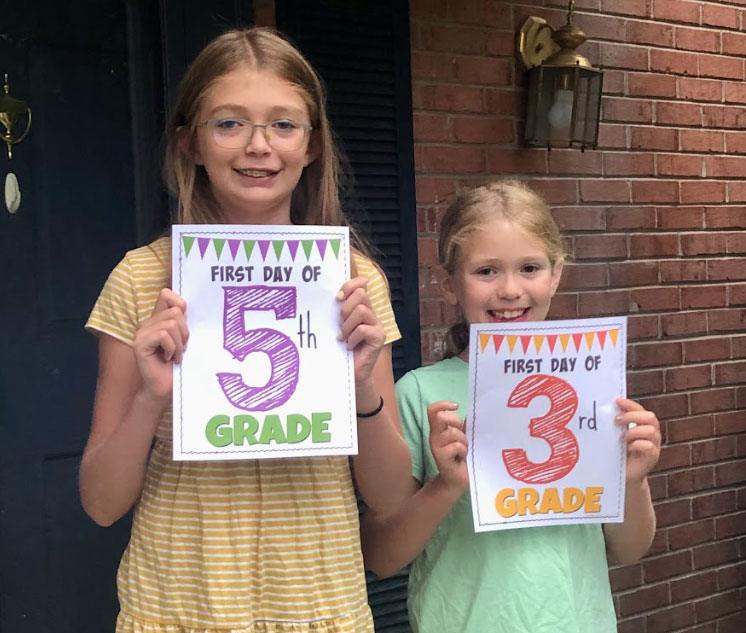

Tracy Compton, whose daughters Lucy and Morgan, attend a Fairfax elementary school, said she can understand why some students get frustrated with the service and don’t use it. Lucy, her oldest, tried the platform last year to prepare for a test on adding and subtracting fractions. But it took 15 minutes waiting in a Ticketmaster-like queue and figuring out how to use the laptop’s camera to photograph Lucy’s worksheet before a tutor got on the phone.

She said both daughters remain two years behind in reading and math.

“I can’t turn Tutor.com on and say, ‘Fill the gap,’ ” she said. “How does a second grader know they are not reading on level and what vowel sounds they need to focus on?”

Loeb and her colleagues at Brown found similar challenges when they examined a charter network, Aspire Public Schools, that uses Paper. Less than 20% of students in a sample of 1,188 signed on to the program. Participation increased to 26% when messages went to both parents and students. But some only signed on once, and students with the worst grades were still the least likely to use it.

Leaders of both Paper and Tutor.com said teachers are increasingly connecting students to the platforms during the school day, which can increase student use at home. Last year, in-classroom use accounted for a third of all Tutor.com sessions, Park said.

“Uptake increases with time and dedicated effort, and we are working together with Fairfax leaders to build awareness about the program,” said Sandi White, senior vice president for institutional partnerships at Tutor.com and Princeton Review.

Even before the Brown study, Paper was tweaking its model to improve engagement, CEO Philip Cutler said in an email. The company added math games and college essay reviews for students preparing for college.

The Brown research, he said, shows that students who take advantage of it make gains — and are more likely to pass all their classes.

Loeb noted that offering students a mix of both high-dosage tutoring and on-demand help makes sense.

“Districts are using a variety of different approaches, she said, “and in the end, that could be the right model.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter