Students in 4-Day-a-Week Schools Can Suffer COVID-Level Learning Losses

Doss, Phillips & Kilburn: Our research finds cutting back from 5 days may save money and boost morale, but it hurts kids' academic achievement

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The past two decades have seen an explosion in the adoption of the four-day school week. Though the policy has been documented as early as the 1930s, only 257 schools in the country had adopted it by 1999. Yet by 2019, over 1,600 schools were on a four-day schedule. There are no signs that the pace is slowing.

Missouri is one of the newest states to see exponential growth in the adoption of this policy. In 2009, no district in the state had a four-day school week; but, as of the 2022-23 school year, about 25% are now on that schedule. Generally, most of the schools and districts adopting the policy are rural and west of the Mississippi River.

Against this growing trend, however, there is increasing evidence that, by and large, a four-day school week causes student achievement to suffer. To study the policy’s effects, we looked at a variety of outcomes in six states— Colorado, Idaho, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma and South Dakota — five of which had the student achievement data we needed for the study. We compared achievement in English and math in grades 3 through 8 in schools that adopted the four-day school week against that of their five-day-a-week peers. We found that students in four-day school week districts fell behind a little every year. Though these changes were small, they accumulated. We estimate that after eight years, the damage to student achievement will about equal that caused, according to some estimates, by the pandemic. The potential long-term learning deficit in student achievement from the four-day school week is, our findings suggest, not trivial.

Why, then, is the policy so popular? For one thing, district leaders cannot see the harm. We found that school leaders, teachers and parents in districts with a four-day week reported that test scores were equal to, or even better than, results from before the policy was adopted. Our analysis confirmed that, by and large, exam results remained the same or went up year to year, even after the shorter week was adopted. But if school leaders were able to see the bigger picture of what was happening outside their district, they would realize that students in five-day-a-week schools were progressing faster. The four-day students were actually, comparatively, falling behind. In other words, their performance would likely have grown faster if their district had never adopted the four-day school week.

The ideas behind the policy are simple and appealing. A shorter week makes it easier to staff schools, a particularly challenging task for rural schools, due to their geographic isolation and lower salaries. Proponents of the four-day week also say a shorter workweek could get teachers to reconsider leaving their job, or bring retirees back into the classroom. It could reduce burnout and improve job satisfaction, and it could attract teachers from neighboring five-day school week districts, even if pay is lower in the four-day district. For districts facing budget shortfalls, the shorter week could save money on, for example, buses, school lunches, substitute teachers and hourly employees, and spend it to preserve staffing levels or hire specialized staff such as reading coaches.

Indeed, in the 12 rural school districts we visited, school administrators, teachers, students and parents reported that the shorter week did indeed improve school morale. Teachers reported feeling less burned out and missing fewer instructional days due to illness or exhaustion. And while they spent time working on school tasks like grading and lesson planning over the weekend, they had more time to prepare for the coming week.

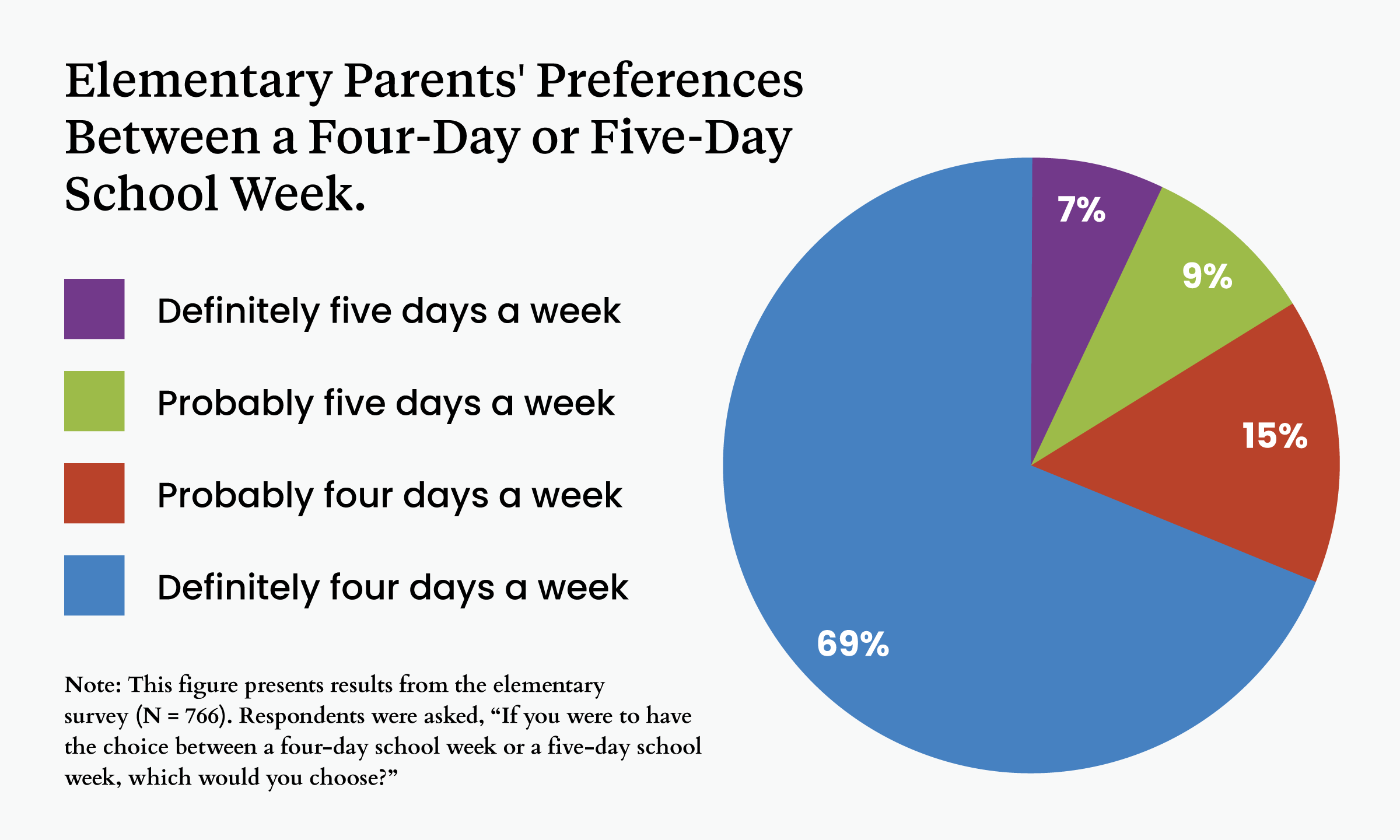

In a few schools, teachers also reported delaying retirement due to the shorter work week. Some even told us they were now willing to drive longer distances, and accept reduced wages, to work in a school that had adopted a four-day week. Students and parents were, by and large, also very satisfied with the shorter week. It allowed teachers, students and parents time to recover from the general stresses of school (e.g., early start times, homework, athletics) and spend more time at home with their families or engage in outside activities.

But even these perceived benefits have shortcomings. Take, for example, the recruiting advantage a four-day school week gives a district. This works only if neighboring districts still have five-day weeks, and even then, it is likely a short-term gain. If a district with lower pay but a four-day week successfully poaches teachers from a district nearby, what’s to stop those same districts from adopting the same policy and winning its teachers back? Indeed, the strongest predictor of a district adopting a four-day school week is proximity to a district that already has one. Teachers have a strong preference for working close to home, so when all surrounding districts operate on the same schedule, the four-day week ceases to be an attractive perk in making long-term employment decisions.

More generally, the four-day school week is being used to sidestep deeper underlying issues that are enduring, complicated and difficult to fix. For example, in our study, we found that the most common reason districts adopted a four-day week was to reduce costs on the expenses named above. Rural schools in particular have tighter budgets than urban ones because transportation costs more and rural areas tend to be poorer, leading to lower local school funding levels. Overhead costs are also higher because rural schools serve fewer children, and continued reductions in state funding makes these districts less able to sustain the costs of running a school. Lastly, while the four-day week might temporarily attract talent, it does not address the longer-term teacher shortages caused by factors such as high stress and relatively low pay that is not keeping up with inflation or other college-educated or advanced degree professions.

A better approach to improving outcomes for both students and teachers would be to address the root cause of the challenges schools and districts face, including insufficient and inequitable funding and teacher and student stress. Though the four-day school week can, at first, seem like an appealing solution to some of the problems that beset schools across the United States, in the long run the benefits may not outweigh the drawbacks—both in slowing learning, and by papering over the deeper issues schools and teachers face.

This essay represents the opinion of the authors and not necessarily those of the RAND or the University of New Mexico.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter