New Study: Kids Who Scored Worst on NAEP Missed the Most School Before the Test

Jordan: Link between dismal results & absenteeism suggests districts looking to fight learning loss should invest in getting students back in class

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This analysis originally appeared at FutureEd.

The results from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress rattled the education sector, pointing to learning loss in math and reading on a national scale during the pandemic. Pundits have tied the test score declines to prolonged school closures, student mental health issues and an easing of academic rigor in many schools.

But a new analysis by a former senior federal education researcher suggests another potential contributing factor: the extraordinary number of students who have missed substantial amounts of school. We know from state data that chronic absenteeism, frequently defined as missing 10% of the school year or roughly two days a month, has increased rapidly since the pandemic began, doubling in some states. And we know from research that students who are chronically absent are less likely to master reading by the end of third grade and more likely to drop out of high school.

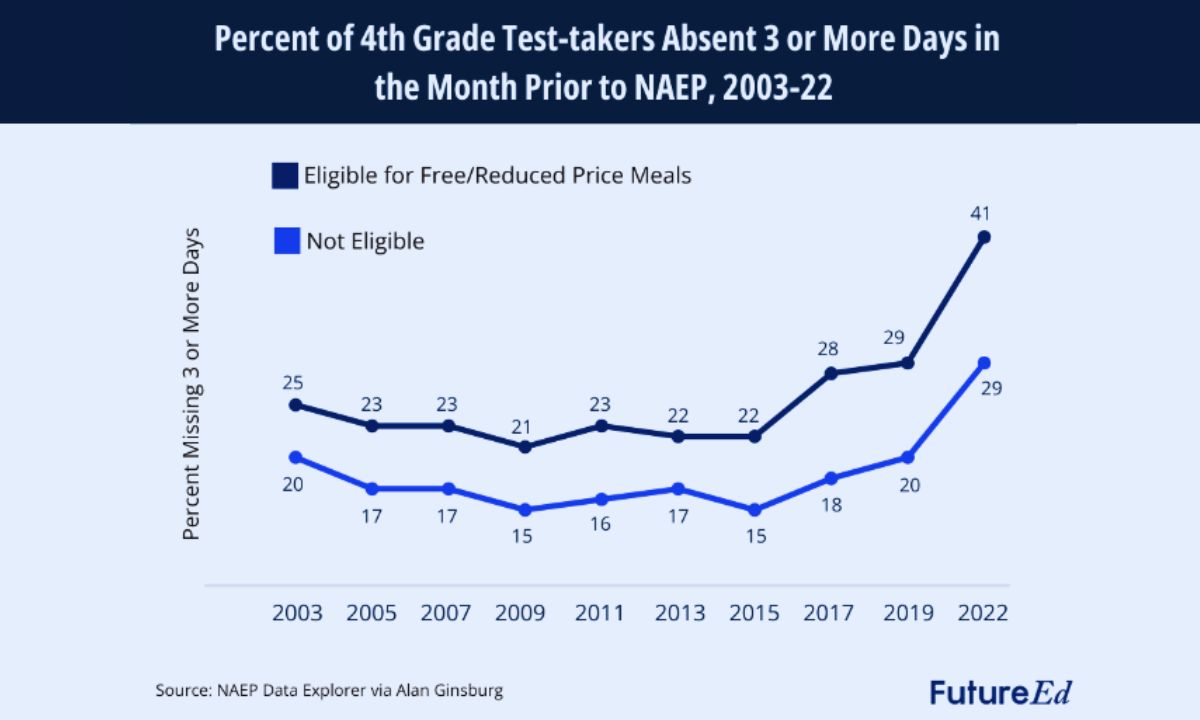

We can’t know exactly how many students taking the NAEP were chronically absent. But each time the test is administered, students are asked how many days they missed in the previous month. Education researcher Alan Ginsburg, a former director of the U.S. Department of Education’s Policy and Program Studies, analyzed the results of that question from the past several years and found that the rate of low-income fourth-grade NAEP test-takers who reported missing three or more days the month before taking the exam climbed from 22% in 2015 to 41% in 2022.

For more affluent students, those who don’t qualify for free and reduced-price meals, the absenteeism rate in the month before taking the NAEP went from 15% to 29% in the same period. There were similar trends among eighth graders, suggesting that many of the same forces affected attendance among elementary and middle school students.

Ginsburg found a correlation between missed days and lower NAEP scores: Fourth graders who said they missed three or more days in the previous month scored 17 points lower on the reading test than those who missed no days and 12 to 13 points lower than those missing one or two days, regardless of poverty level. Given that researchers suggest that 10 to 12 points is roughly equivalent to a year’s worth of learning, those are substantial differences.

On the eighth-grade math test, low-income students who missed three or more days in the previous month scored 15 points lower than those with no absences and 10 points lower than those missing one or two days. For students who don’t qualify for free or reduced-price meals, the gaps were 17 and 11 points, respectively.

The NAEP attendance question is a fairly crude metric, relying on students’ recollection of their absences in a single month (though the students’ reports largely mirror state-reported increases in chronic absenteeism since the pandemic). And you can’t draw a straight line between attendance and the NAEP score declines; there are certainly other contributors.

But common sense and considerable research suggest that students perform better academically when they show up for school regularly. Districts looking to close the learning gaps that emerged during COVID would do well to invest in the sort of evidence-based strategies that can bring students back to school.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter