Public Invited to Help Decide What Stays and Goes in St. Paul School Budget

As federal COVID aid runs out, new oversight panel will use real-time data to gauge which learning supports worked — and which to cut.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Earlier this year, St. Paul Public Schools drew national recognition for transparency in deciding how its pandemic relief funds are used. Now, as the last of that unprecedented influx of federal dollars is being spent, the district is inviting the public to help determine how well the money was invested — and decide which efforts to fund in the next budget.

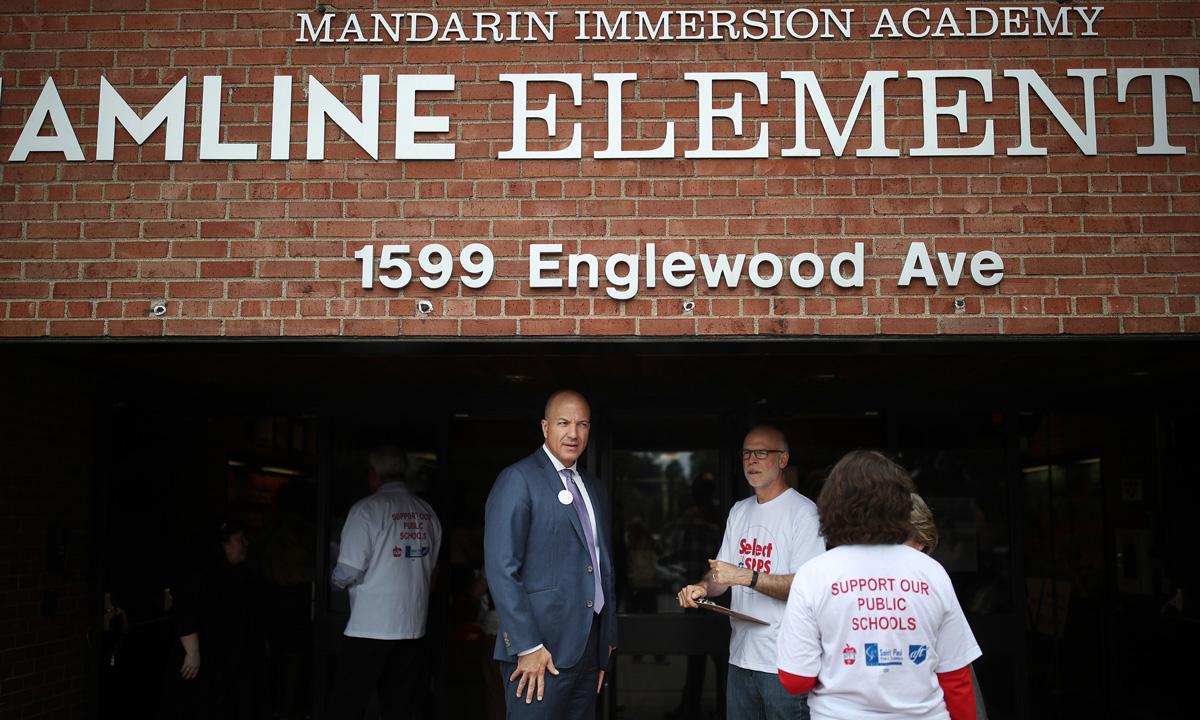

Four of 10 seats on a new finance advisory committee will be filled by community members, starting in a few weeks — the first time the public has been given a formal role in fiscal oversight. In an effort to recruit new voices, priority will be given to people who have not previously volunteered with district governance but have ties to schools and some knowledge of finance. Three school board members and three district executives, including Superintendent Joe Gothard, will round out the committee.

Over the summer, as the school board considered the current $1 billion budget, community opposition to some cuts convinced district leaders that as public as spending decisions about pandemic relief had been, even more outside participation was needed.

St. Paul Public Schools is one of the most diverse in Minnesota, serving one-fourth of the state’s English learners, with concentrations of Southeast Asian and East African students. Less familiar populations, including Karen, Burmese and Bhutanese families, are also expected to grow. When the district first started planning to address the pandemic’s learning losses, leaders knew that the demographics meant schools would need numerous strategies. To identify them, they tapped dozens of community organizations.

When the federal aid started flowing, trying to both incorporate feedback from so many groups and speed up the hidebound bureaucracy that keeps money moving seemed impossibly daunting, says Stacey Gray Akyea, the district’s executive chief of equity, strategy and innovation.

But finding time for community input is already yielding dividends in making the system more nimble and assuring that limited funds are spent on students’ most pressing issues. Instead of waiting for multi-year evaluations, looking at early evidence can help leaders decide whether to put more energy or money into an initiative.

“We’ve got to continue to coalesce around student learning needs,” Akyea says. “Everything else really needs to be able to shift according to what we need to be able to do to do what is best for our students.”

To this end, a year ago district leaders created a series of dashboards tracking, in real time, key information about each of the dozens of strategies initially adopted. As they began using the data to make decisions much more quickly than usual, they shared them publicly. They hoped to help the public understand, by sharing evidence of where change is needed, why some programs got boosts while others were cut.

The effort drew national and local attention from the U.S. Department of Education, which invited district leaders to present their work at a webinar for other districts; from the Council of Great City Schools; and, most recently, from the Minnesota Association of School Administrators, which cited the approach in naming Gothard the newest superintendent of the year.

Whatever ultimately ends up in the budget to be approved next June, school board members will have to justify their choices to the public. Better, say district leaders, to start those conversations now.

Case in point: The relief aid allowed the district to test new strategies for closing longstanding racial and socioeconomic academic gaps. Funding those that turned out to be the most effective seems like an obvious priority. Yet new concerns have surfaced in the years since in-person schools were shuttered.

Chronic absenteeism and student safety are much bigger community concerns now, for example, than they were in 2020. After schools reopened for in-person instruction, it became clear that giving older students passes for public transit, now plagued by rising crime, wasn’t as likely to get them to school as it had been. So St. Paul used some of the aid to raise driver pay so it could reinstitute school bus routes.

“We did some student surveys last spring after a lot of tragic incidents in and around our schools,” says Innovation Office Director Leah Corey, one of the district leaders who created the dashboards tracking how well pandemic interventions have worked. “Yellow buses came up a lot as something that students and parents missed. They thought they would be safer and be more on time and more accountable to get to and from school if they had a yellow bus.”

Khulia Pringle, the National Parents Union’s Minnesota state director, has applied to join the committee. If she is chosen, she says, she will also raise safety issues. The parents she works with want more orderly schools, she says, but believe that would better be accomplished by increasing the number of community groups with a presence in schools than by reviving contracts with local police.

As painful as these choices sound, St. Paul may hit fewer speedbumps navigating them than other large school systems.

Right now, administrators everywhere are taking their first painful steps toward creating budgets for the 2024-25 academic year. For many, this means finally confronting the so-called fiscal cliff, a precipice that education finance experts warned of three years ago when Congress approved $190 billion in recovery aid. Now, with federal funds drying up in September 2024, these districts are figuring out who to manage with dramatically reduced funding.

Lawmakers and finance experts had hoped much of the aid would be used to help students bounce back from pandemic learning losses, but many school systems instead used it to plug pre-existing budget gaps. Frequently, the mounting deficits were caused by years of falling enrollment driven by declining birth rates.

Compounding the crisis, a record number of families moved their children out of district schools during COVID, accelerating the need for painful structural changes. Instead of helping their remaining students rebound, lots of districts spent relief funds staving off unpopular decisions such as closing schools and laying off staff.

Between the start of the 2019-20 and 2021-22 school years, St. Paul Public Schools lost 10% of its students, accelerating a trend decades in the making and projected to continue. Operating a large number of drastically underenrolled schools, in fall 2021 the board decided to close several and consolidate others.

The move allowed the district to spend most of its $319 million share of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund on strategies tied directly to meeting students’ needs. With an aim of pushing the system to respond more nimbly to internal data showing what’s working and what isn’t, district leaders created a public dashboard for each expenditure outlining its goal and tracking progress.

That information should help the new committee be strategic in considering what recommendations to prioritize in 2024-25.

For example, the panel will likely be asked to consider continuing a program that put 105 literacy specialists in elementary and middle schools to work with small groups of struggling students. In addition to allowing the district to retain highly effective educators even as it closed buildings, the effort — known as What I Need Now — quickly started to boost reading rates.

Test data show that the more than 4,000 kids in the program are learning to read more quickly than their peers. The district is nowhere near catching everyone up, however. After an initial dip at the start of the pandemic, reading proficiency rates on annual state exams have stabilized — around 35%.

District leaders are working to extend the program, which will cost an estimated $12 million during the current school year, from elementary to middle grades. They have also instituted a parallel effort in math, training teachers to use data and higher quality instruction in schools where students are struggling.

The district has also had success addressing labor shortages. St. Paul spent $4.6 million in pandemic money creating a team to recruit and retain teachers, administrators and paraprofessionals of color and in areas where job openings are particularly hard to fill. Among many strategies, the new staff has traveled to Historically Black Colleges and Universities, made on-the-spot offers at job fairs and — a rarity in Minnesota — used hiring bonuses to help fill vacancies.

The investment appears to be paying off. Over the summer, as neighboring districts struggled to retain educators of students with disabilities, St. Paul offered $10,000 signing bonuses to special education teachers, filling 70 vacancies in short order. Of the nearly 750 staff hired during that time, half were teachers.

The new finance committee is expected to meet four to six times a year.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter