Lost Learning = Lost Earning, an Equation that Could Cost the U.S. $31 Trillion

New analysis from Stanford economist Eric Hanushek finds U.S. kids lagging international peers in math.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

American students are lagging behind their international peers in the aftermath of the pandemic, according to a new analysis unveiled by Stanford University economist Eric Hanushek. The ultimate costs of the last few years of incomplete learning will total $31 trillion over the course of the 21st century, the scholar finds — greater than the country’s Gross Domestic Product over an entire year.

Released this morning through Stanford’s right-leaning Hoover Institution, the report echoes prior warnings by its author, one of the nation’s most cited experts on education finance. Hanushek has cautioned since the emergence of COVID that the prolonged experience of virtual instruction would meaningfully harm the skills and earning potential of today’s students.

His newest release builds on those predictions by examining the math performance of U.S. students on two standardized tests. One, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), is a worldwide exam comparing American 15-year-olds against adolescents in dozens of other countries; the other, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (often referred to as the Nation’s Report Card) is administered to fourth- and eighth-graders around the United States.

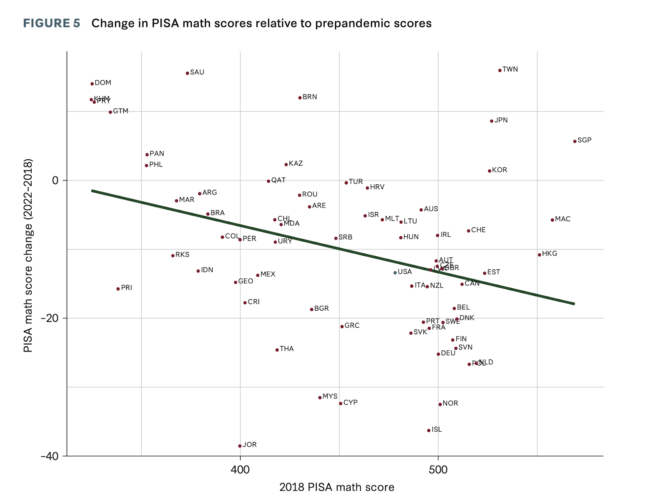

The PISA results, revealed in December, showed U.S. math scores falling significantly between 2018 and 2022, offering more evidence of what federal officials have called a COVID-era “crisis” in that subject. But because other countries saw even larger declines, America’s international ranking actually moved upward slightly, leading Education Secretary Miguel Cardona to issue a statement extolling the Biden administration’s emergency assistance to schools during the pandemic.

In an interview with The 74, Hanushek was much less sanguine, pointing to K–12 students’ persistently mediocre performance in math over the last few decades. After overlaying the NAEP math scores of individual U.S. states onto PISA’s international scoring system, he found that even test takers in the top-scoring state, Massachusetts, ranked below their counterparts in 15 other countries. The lowest-performing American jurisdiction, Puerto Rico, placed below developing nations like Kosovo, El Salvador and Cambodia.

If our best-performing state school system is 16th in the world, that doesn't seem good to me.

Erick Hanushek, Stanford University

“People in the past have said, ‘Massachusetts is doing pretty well, maybe we could get New Mexico going like that too,’” Hanushek said. “But if our best-performing state school system is 16th in the world, compared to the average kids in other countries, that doesn’t seem good to me.”

In general, the analysis shows, the top-line U.S. math ranking on PISA rose primarily because the pandemic’s disruptions to schooling were much more acutely felt in countries like Slovenia and Norway, which had been among the top performers on earlier iterations of the test.

Overall, students in relatively higher-scoring countries on the 2018 PISA exam sustained larger losses during COVID than those in countries that hadn’t done as well previously. Hanushek called the trend a “straightforward” validation of the importance of high-quality schools: Canadian students stood to lose more from weeks or months of online classes than those in less-effective Philippine schools.

“If you weren’t learning very much in school before the pandemic, you didn’t lose as much,” he said. “If you were learning a lot in school before the pandemic, you tended to lose more.”

The United States, long mired in the middle of the international pack, saw somewhat smaller math declines between 2018 and 2022 than the PISA average. Meanwhile, in spite of the clear trend, high-achieving East Asian countries like Taiwan, Singapore, Japan and South Korea actually improved in the subject during the pandemic.

The learning loss exhibited in both NAEP and PISA strongly suggests that the long-term prospects of affected students will be substantially worse than they would have been otherwise. Martin West, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, said this is largely due to the very nature of the American economy, in which skills and educational attainment are more highly prized than almost anywhere else in the world.

“The U.S. is a society in which skills really do matter for economic success,” West said. “What that means is that the impact of learning loss on individual students through their earnings is going to be larger in the U.S. than it might be in a society like Sweden.”

Wide state variation

Hanushek’s total calculation for the cost of learning loss, a staggering $31 trillion through the year 2100, is a figure that would dwarf the economic damage wrought by the business closures and layoffs necessitated by COVID’s spread, or even the years of stalled dynamism following the Great Recession.

The projection is based on prior economic research into the connection between students’ test scores and future earnings. Hanushek further posits that the aggregate slowdown in innovation and human capital development will tend to slow the U.S. economy’s growth over the long haul, burdening even those who didn’t experience learning loss themselves.

The analysis estimates a far greater toll than that of another prominent prediction. In 2022, economists Thomas Kane of Harvard and Douglas O. Staiger of Dartmouth used eighth-grade math results on the NAEP exam to reach a $900 billion future cost following the pandemic. While that estimate pointed to a 1.6 percent decline in students’ future earnings, Hanushek and co-author Bradley Strauss believe that slump will fall between 5 and 6 percent.

Staiger said his paper with Kane represented a “lowball estimate” while Hanushek’s offers an upper-bound projection, adding that most of the discrepancy between their findings likely stemmed from Hanushek’s broader lens on overall growth in addition to direct earnings. Whatever their differences, however, he noted that even marginal losses in productivity could eventually amount to considerable squandered potential.

Even small impacts of the learning loss on future economic growth impose enormous costs on society.

Douglas O. Staiger, Dartmouth College

“There are some other papers that find smaller effects of test scores on economic growth, particularly for high-income countries like the U.S.,” Staiger wrote in an email. “However, as Hanushek and Strauss make clear, even small impacts of the learning loss on future economic growth impose enormous costs on society.”

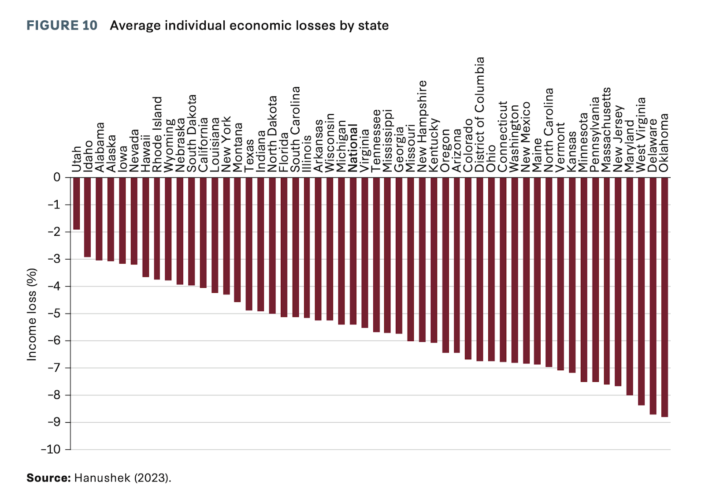

If Hanushek’s analysis proves correct, those costs will be borne unevenly. The largest state economies, such as California, Texas, New York, Florida and Pennsylvania, are all projected to absorb losses greater than $500 billion; their disproportionate burden reflects both the scope of their learning setbacks to this point and the number of future workers living in each.

Individual income losses are also projected to differ considerably depending on location. By the paper’s calculations, students affected by the pandemic will lose less than 2 percent of their lifetime earnings in Utah, where math scores fell the least between 2019 and 2022. In West Virginia, Delaware, and Oklahoma, where they fell the most, former students could forgo an average of 9 percent of their career income.

Sarah Cohodes, an economist at the University of Michigan, said that the inequity of learning loss was a cause for particular concern. While the math performance of all students suffered between 2020 and the present, the losses were especially large for those who were already struggling or navigating critical life changes when COVID emerged. She referred to her own daughter, who wasn’t yet enrolled in a K–12 school when the pandemic began, as an example.

“She lost a year of preschool, but she’s going to be fine — she hung out with me and went to all the parks in New York City,” Cohodes said. “The people I worry about are the ones who were transitioning between elementary and middle school, or who graduated from high school and missed out on some of the final preparations for what comes next.”

The people I worry about are the ones transitioning between elementary and middle school, or who graduated from high school and missed out on final preparations for what comes next.

Sarah Cohodes, University of Michigan

Hanushek, whose preferred strategy for learning recovery is to provide financial incentives to top teachers in exchange for taking on more students, observed that the worst-off students were likely the high schoolers who graduated or dropped out over the last few years. The unsuccessful efforts to mitigate their academic reversals, whether led by state or federal officials, were evidence that education authorities “have not really taken seriously the magnitude of this event,” he argued.

“My calculation is that 17 million kids [affected by the pandemic] have already left school,” Hanushek said. “Once they’ve left school, we have little hope of ever fixing their problems. Universities or firms are not going to make up for the lack of learning that these kids suffered, and each year that goes by, we lose four or five million more kids that will never recover.”

Disclosure: The Hoover Institution provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter