Social-Emotional Learning or ‘White Supremacy with a Hug’? Yale Official’s Departure Sparks a Racial Reckoning

By Linda Jacobson | April 6, 2021

As schools across the country grapple with issues of historical discrimination, the director of a prominent SEL program argued that some inclusion efforts could get its curriculum “banned,” according to emails obtained by The 74.

Updated April 7

Attending a mostly white boarding school in Connecticut allowed Dena Simmons to escape the danger of her poor, Black and Latino neighborhood in the Bronx, New York. But it also separated her from her culture and made her feel like she didn’t belong. “There is emotional damage done when young people can’t be themselves,” she said six years ago during a TED Talk that has received almost 1.4 million views.

That’s why Simmons, who became assistant director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence in 2018, worked to make the center’s popular K-12 program on understanding feelings more meaningful for marginalized students. She pushed to include figures such as former President Barack Obama and girls’ education activist Malala Yousafzai in lessons and challenged teachers with bold statements about schools being systems of white supremacy.

Her drive for cultural relevance, however, repeatedly clashed with the views of her supervisor, Marc Brackett, the center’s prominent director and best-selling author of Permission to Feel.

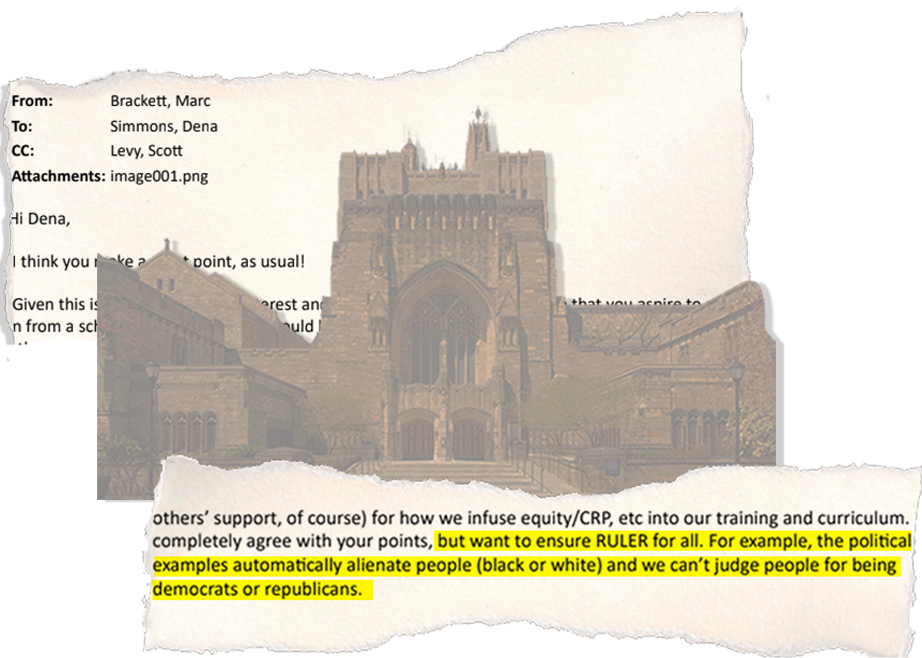

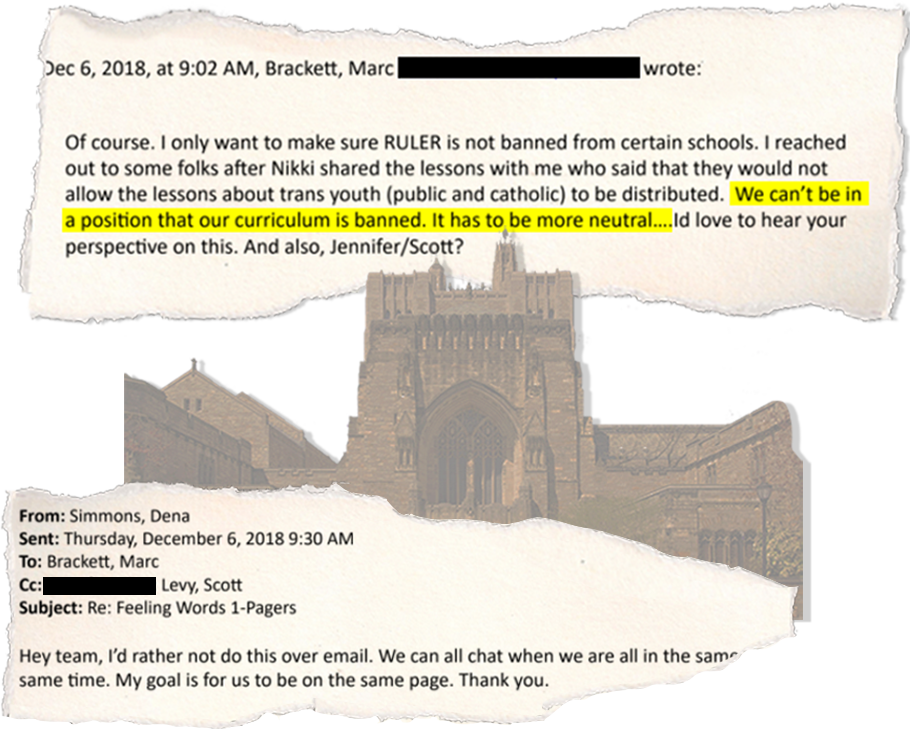

“The political examples automatically alienate people (Black or white) and we can’t judge people for being Democrats or Republicans,” Brackett wrote Simmons in one of several emails and documents shared with The 74.

His insistence on staying on the political sidelines ran afoul of Simmons and others at the Yale center who viewed his stance as tone deafness toward issues of historical injustice. Their lessons — for example, using a book about a transgender boy to teach about feeling understood — might get the curriculum “banned” in some parts of the country, Brackett said in one email. The conflict has put the center in the middle of a controversy that has rippled from the university to the larger world of what has come to be known as social-emotional learning.

Simmons, 37, resigned from her position in January, seven months after she was targeted by anonymous racial slurs during an online Yale event to memorialize the death of George Floyd. She left, she told the university at the time, due to a “hostile work environment” at the center, where she was subjected to “unconsented hair touching” and once received a reprimand from a supervisor for calling out social-emotional learning practices she viewed as harmful to students of color.

In interviews, four other former staffers supported her account, describing what they saw as an unwelcome atmosphere at the center toward issues of diversity and inclusion.

“There was no emotional intelligence afforded me,” Simmons told the 74. “I hope to push the field and institutions to do better — to put their actions where they say their values are.”

In a lengthy statement on her resignation sent to roughly 2,500 schools and organizations it works with around the world, center leaders said they were “deeply disheartened by our colleagues’ hurtful experiences at Yale.”

“We want to stress that we do not tolerate discrimination or bias in any form,” they wrote. “We care deeply about our team’s well-being and safety, and we continuously strive to create a workplace that fosters a sense of belonging where all people feel valued and connected.”

Despite strides toward “creating and sustaining an antiracist workplace,” the statement acknowledged “there is much more work to do.” Contacted by The 74, Brackett said he is taking “a pause on interviews” and sent a link to his center’s position on diversity, equity and inclusion — developed after the online incident.

The episode at one of the nation’s most elite universities offers a window into how social-emotional learning programs — and schools more generally — are grappling with issues of historical discrimination as well as a growing backlash from those who say such efforts are politicizing the curriculum.

“As goes the consciousness of the country, so goes education,” said Robert Jagers, vice president of research at the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL), a hub for research and policy expertise in the field. “There is a measure of urgency that was not present two years ago.”

Mood Meters and Meta-Moments

In many ways, the Yale schism reflects the enormous growth social-emotional learning has experienced since the term’s first invocation at a 1994 conference. Today, the concept is ubiquitous. It is not unusual for large school districts to have whole departments devoted to helping students form positive relationships, manage difficult emotions and make sound decisions. It’s also big business, drawing $21 billion to $47 billion annually on programs and teacher training, according to a 2017 report.

While some criticize the field for “fuzzy” definitions and unclear targets, a formidable body of research now says social-emotional learning can improve social behavior and lead to long-term academic success.

After completing post-doctoral work in psychology with Peter Salovey, now Yale’s president, Brackett became one of the field’s early pioneers. Like Simmons, he came to the study of human emotion from painful personal experience. In an interview last year with Brené Brown, author of The Power of Vulnerability and Daring Greatly, he described being sexually abused as a child and turning to his uncle, a teacher, for help.

“When I disclosed what was happening, he was the only adult who was there for me,” Brackett said. “He just listened. He didn’t say, ‘Toughen up!’ like my father did, and he didn’t have a breakdown like my mom did. And God bless my parents, they did everything they could, but they just had no resilience, they had no strategies to deal with their feelings.”

His center’s signature program is RULER — an acronym for “recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing and regulating” emotions. The “Meta-Moment,” one of its stock tools, prompts students to imagine their “best self” when responding to tense situations. Lessons on “feeling words” ask students to study how a book character or a well-known person might have felt in a particular situation.

“Marc’s vital voice regarding the connection between emotions, cognition and learning has resonated in the field,” said Chi Kim, CEO of Pure Edge, a nonprofit that provides health and fitness programs for schools and funds research in social-emotional learning.

The Yale center, which sits in the medical school, draws in millions of dollars in grants, including at least $5 million in research funding from the U.S. Department of Education since 2012. It has even earned the endorsement of current Secretary Miguel Cardona. As state chief in Connecticut, he hired Brackett’s center to give all educators in the state access to a 10-hour course, funded in part with $500,000 from Dalio Education, a state foundation. CASEL cites RULER as an example of a program based on research, and Brackett sits on its board.

He has also brought to the field pop-culture cachet. He teamed up with Lady Gaga in 2015 for a summit on how teens feel about school and appears frequently on TV talk shows. Even parents who don’t know RULER or recognize Brackett’s name are familiar with the “Mood Meter,” which teaches children to associate feelings with colors. The resulting boards of multi-hued Post-it Notes produced by parents and teachers have become mainstays on Pinterest.

A former middle school math and English teacher in the Bronx, Simmons joined the center in 2014. She believed in its mission and called the opportunity “a dream come true.” Her doctoral studies had focused on how middle school teachers can address bullying. Now, she wanted to help schools become more compassionate places for marginalized students.

But as the program grew, so did Simmons’s view that the center’s leaders saw equity as an “add-on.” She became convinced that common practices in social-emotional learning, such as taking deep breaths in times of stress, wouldn’t serve students of color well.

“Try telling a child in poverty to breathe through racism,” she said in an interview. “That is insulting.”

She recruited others with classroom experience to the center and blended Learning for Justice’s Social Justice Standards — like showing “empathy when people are excluded or mistreated” — into RULER materials.

Susan Rivers, who co-founded the center with Brackett in 2013, recalled that Simmons “emerged as an education leader, despite not having the support, encouragement or collaboration to do anti-racist, inclusive work while at Yale.”

“She asks really tough and essential questions about equity in education, and she has the courage and conviction to do and lead the work,” said Rivers, who left the center in 2016 and now runs iThrive Games, a foundation that supports game-based learning for teens.

That quality often put Simmons at odds with the center’s leadership. In commentaries such as 2019’s “Why We Can’t Afford Whitewashed Social-Emotional Learning,” she argued that sidestepping the “larger sociopolitical context” in which students live keeps them from developing skills to confront hate and injustice. Ignoring that background, she said, could turn their teachings into “white supremacy with a hug.” That statement, she said, earned her a warning from Linda Mayes, director of the Yale Child Study Center that oversees the emotional intelligence program, to be more careful with her words.

Mayes declined to comment on the incident.

‘Dead presidents’

In charge of teacher training and curriculum, Simmons directed her energy toward integrating that real-world context into RULER’s “feeling words” — the vocabulary students develop to describe their emotions and match them with the red, blue, green and yellow quadrants on the Mood Meter.

For “hopeful” — in the yellow, energetic and highly pleasant range — Simmons thought Obama, author of 2006’s The Audacity of Hope, would be a natural fit. But at a lunch meeting with two other center leaders, Brackett blanched at the idea, she recalled.

“He said … that if we focus on presidents, we should only focus on dead presidents,” she said. “He must not have realized that all of the dead presidents were white men.” The two others she said were present — Scott Levy, the center’s executive director, and Nicole Elbertson, the director of content and communications — did not respond to requests for comment. Levy announced his resignation from the center March 10. Karen Peart, a spokeswoman for the Yale School of Medicine, said he is “pursuing another opportunity” but will remain on the center’s board.

The center’s leaders ultimately acquiesced on using those examples, but drew the line on others. For a lesson on “despair,” Karina Medved-Wu, who worked on RULER’s lessons for afterschool programs, dipped into current events and wrote a vignette about an undocumented parent stuck in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center.

The example was replaced with the story of a runaway cat.

Medved-Wu noted the irony of a workplace devoted to emotional intelligence where many workers felt uncomfortable sharing their emotions.

“If Black employees, non-Black employees of color, employees who have self-identified as LGBTQ+and employees with disabilities do not feel safe, valued or heard in-house,” she asked, “then what biases and messaging are being sent locally and globally?”

She also proposed a fifth-grade lesson about The Other Boy, the book about a transgender child that sparked pushback from Brackett. “We can’t be in a position that our curriculum is banned,” he wrote in an email to Simmons and other staff members. “We have to be neutral.” To respond to his concerns, Medved-Wu included an alternative assignment: a video in which a father took a forgiving approach to confronting a boy who had bullied his son.

In October 2019, she said she spoke to Darin Latimore, the medical school’s deputy dean for diversity and inclusion, who indicated he had launched an investigation into the working environment at the center; at the time of their talk, he told her he had spoken to 15 people, she recalled. Latimore did not respond to requests for comment.

Peart, the Yale spokeswoman, declined to discuss the results of his “climate assessment,” but said without elaboration that “action is in process to address the themes gleaned during the review.” The center’s goal is for RULER to be “non-partisan,” she said, adding that it regularly seeks feedback on content to make it more inclusive. A school that wanted to use The Other Boy, she said “would be met with our full support.”

To the bewilderment of some staffers, Brackett appeared to have no resistance to such themes in his personal life. Brackett, who is gay, supports finding ways for young people “pushing the boundaries of gender/sexual identity” to feel accepted, and he recently completed a documentary with his cinematographer husband on a camp for youth devoted to “exploring gender diversity.”

But inside the center, staff members say they heard a different message. “I recall him frequently emphasizing … that the appeal of our work had to be for everyone,” said Sarah Kadden, a former program manager for early childhood.

Simmons and Medved-Wu suspect Brackett’s motivation for keeping the lessons free of controversy was financial. A six-week training institute for three district staff members costs $6,000.

“If RULER were to be banned, it would impact the bottom line,” Simmons said.

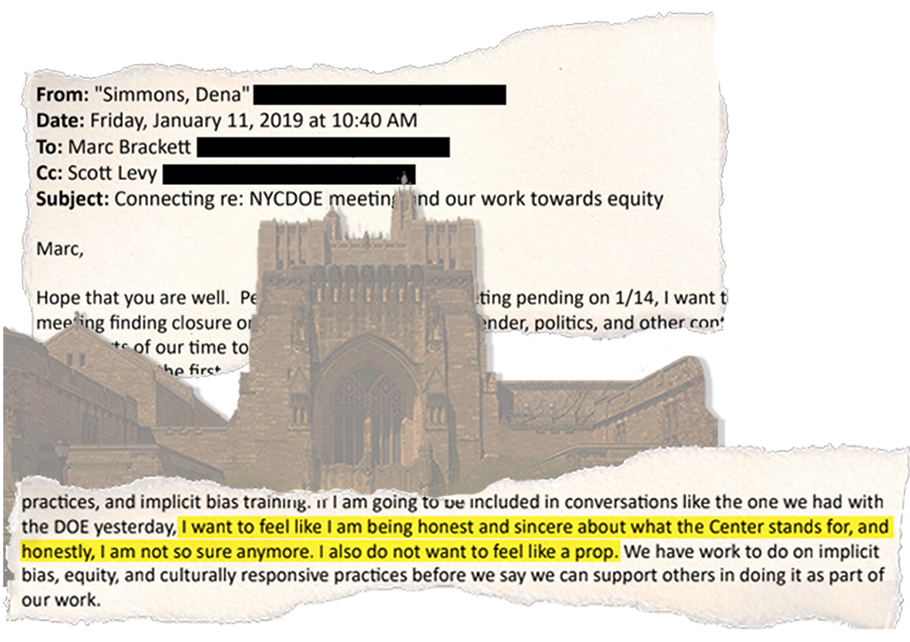

The issue most important to Simmons — equity — was where she felt the least support. She had been pushing for years to brand the term into the center’s mission statement. In 2019, Brackett proposed in an email that she “create the vision … for how we infuse equity/culturally responsive practices, etc. into our training and curriculum.” By that point, Simmons said, the center was sending mixed messages, pushing inclusion while resisting her attempts to broaden the curriculum. In one email, she told Brackett that she did not want to become “a prop” for the center’s work on diversity.

“We were discouraged from raising equity issues, such as the school-to-prison pipeline, racist discipline practices [and] the cultural mismatch often found between students and teachers,” said Kadden, now a social worker in Connecticut’s New London Public Schools.

Then came the Zoom bomb.

On May 25, the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody sparked an outcry in cities and campuses across the country. In early June, thousands of Black Lives Matter protesters flooded the streets of New Haven, where Yale is located, presenting a list of demands, including the removal of resource officers from local schools. Weeks later, during an online event devoted to racial healing held by Yale’s Child Study Center, Simmons was reading a poem when several anonymous gate-crashers interrupted her with racial slurs, both verbally and in the chat field. Simmons logged off of the event, which was not password protected, but returned at the urging of colleagues. The harassment resumed.

In its statement, the Yale emotional intelligence center decried the “horrific, racist Zoom bombing” and said it had taken steps to curb its online “vulnerabilities.” Leaders have offered workshops on cultural sensitivity, hired a chief diversity officer and scrutinized RULER to “ensure it is equitable and inclusive,” the statement said. But Simmons, who took a seven-month medical leave, said the experience followed a pattern of incidents in which she felt dehumanized, such as colleagues touching her hair and calling it exotic. She left the university Jan. 19, the day she was supposed to return.

For those who view Simmons as a leader, not only in social-emotional learning but in the broader anti-racist movement, her departure raises troubling questions.

“Dena’s star was certainly on the rise … because she brought a perspective in content that was transformational,” said Andre Perry, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “I don’t know how you lose somebody like that.”

Some districts that use RULER and sent teachers to learn from Simmons have taken note of her departure. An official in the Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma said any further expansion of RULER in the district is “on pause [until we] see the response from the university.” And the executive director of the Tauck Family Foundation in Wilton, Connecticut, which funds RULER in Bridgeport early-childhood programs, said she wants to see what “progress has been made in addressing the issues raised” by Simmons’s resignation before continuing its support.

Many schools are playing catch-up in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests, which sparked a reckoning on issues of race in education, from hiring practices to teaching history. “I think that Marc and Yale feel constrained about what they can do and they can’t do,” said David Osher, vice president and fellow at the non-partisan American Institutes for Research. “Probably many organizations prior to this past summer were … more timid about taking on issues that involved being explicitly anti-racist.”

Osher’s work on school safety and student engagement includes social-emotional learning. He’s collaborated on grants with the Yale center and credits Brackett’s work with helping him understand the importance of training adults before children. But he noted that curriculum developers must create programs that “play in both blue and red states.” Of the Yale center, he added, nothing about Simmons’s departure “would make me stop working with them.”

The push for educators to address structural racism has prompted its own outcry, turning critical race theory and new histories such as The New York Times’ “1619 Project” into fodder for the nation’s ongoing culture wars. At Smith College, for example, a former staff member has attracted a passionate YouTube following for criticizing the school’s insistence that employees undergo anti-bias training that centers on white privilege. Several academics recently formed the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism to combat what they see as an overly cynical emphasis on race, gender and sexual orientation, rather than “common humanity.”

“There is no such thing as a values-neutral [social-emotional learning] program,” said Ian Rowe, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute and a member of the foundation’s board. “But integrating reductionist ideas that carry oppressor [and] oppressed identities based on race will only perpetuate false, corrosive notions of superiority and inferiority.”

‘Sins of our history’

With Yale behind her, Simmons is free to approach social-emotional learning her way.

She has launched LiberatED — a curriculum with equity at the center — and next year, St. Martin’s Press will publish her book, White Rules for Black People. “I needed my voice to ring louder than other people’s doubts, slights and limitations,” she wrote recently. “I left so that I could save myself, so that I could dream. And I left so that I could invest my time into changing the very system that failed me and is failing so many others.”

But her message still rattles. When she spoke in February to teachers in a predominantly white, affluent Chicago suburb, a writer for a right-wing website called out some of Simmons’s more provocative statements, such as saying the nation’s education system is “based on a foundation of whiteness.” Simmons later tweeted that coverage of the event sparked threats and hate mail.

Dan Iverson, president of the Naperville Union Education Association, said he heard complaints from a few participants, though he and most teachers present saw the speech in a more positive light.

“It’s not a sin to be white,” Iverson told The 74. “We’ve always had a hard time in this country with the idea that the sins of our history are still relevant. It’s inherently very difficult to exist in a place where you can be OK with who you are as a white guy, but to understand you are better off.”

Flare-ups like the one in Naperville do not surprise Kamilah Drummond-Forrester. For years, she has asked teachers to examine their attitudes and biases toward students as part of the training for Open Circle, a social-emotional learning program based at Wellesley College, an elite liberal arts school in Massachusetts. The program is used in about 300 schools across the country.

In workshops, teachers sometimes drop comments, such as, “Those students don’t care about school,” or “Their parents aren’t interested,” said Drummond-Forrester, the program’s former director. Teachers call out what they view as “coded language” toward Black and Hispanic students, only to anger colleagues who think they’re being branded as racists.

But like Simmons, Drummond-Foster views such encounters as necessary. “You can’t talk about teaching skills around social awareness devoid of the systems that these kids are navigating,” she said.

That’s not the only thing they have in common. Just 10 days after Simmons’s resignation, Drummond-Forrester left her position as head of the Wellesley program.

In a statement, the college’s Centers for Women, which includes Open Circle, called Drummond-Forrester “a thought leader” for her work exploring social-emotional learning “through an equity lens,” and said staff would continue to work with her on other diversity efforts. Echoing Simmons’s concerns, Drummond-Forrester said the responsibility for equity work fell on her shoulders because she is Black.

“I was burned out,” she said.

Disclosures: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to RULER and The 74. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provides financial support to the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and The 74.

Lead Image: Dena Simmons spent seven years striving to make the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence’s popular RULER program more culturally responsive. Now she’s leading her own efforts to incorporate equity into social-emotional learning. (Nuria Rius for The 74)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter