The Unintended Consequence of Brown v. Board: A ‘Brain Drain’ of Black Educators

In 74 Interview, author Leslie T. Fenwick said the effects were so damaging that ‘the nation’s public schools still have not recovered’

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

American students have attended school for nearly 70 years under the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which outlawed racial segregation in public schools. But a new book uncovers a little-known by-product of the case: Educators and policymakers in at least 17 states that operated separate “dual systems” of schools defied the spirit of Brown by closing schools that served Black students and demoting or firing an estimated 100,000 highly credentialed Black principals and teachers.

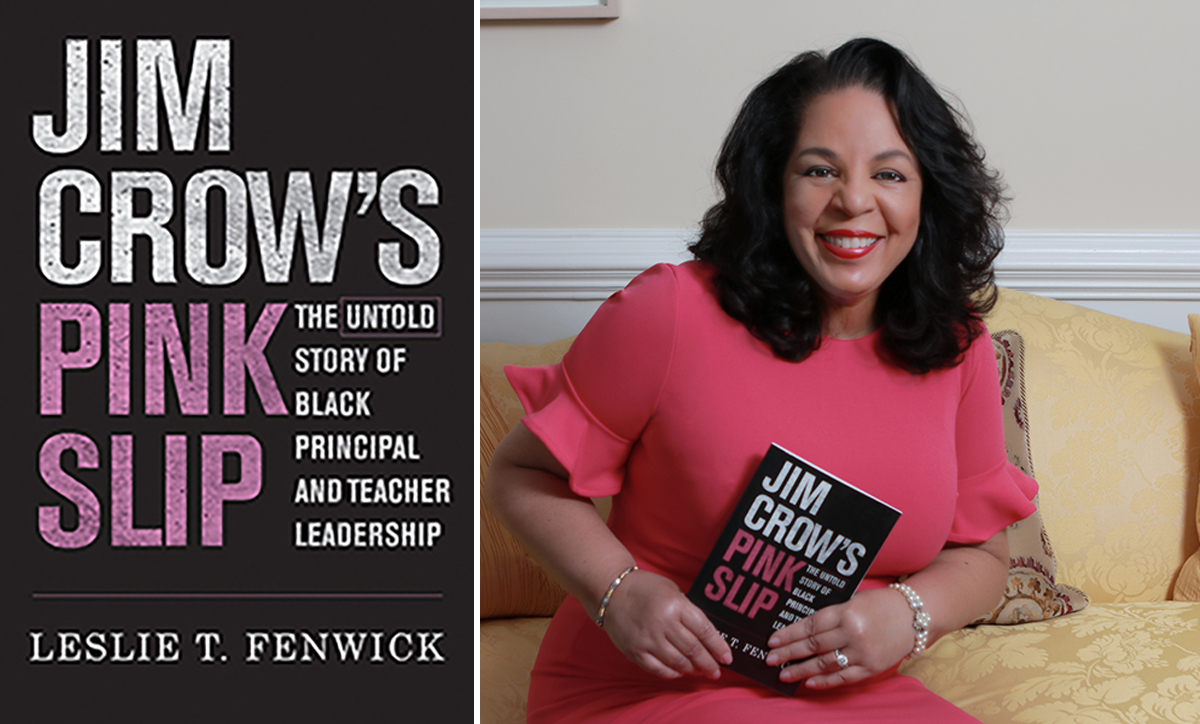

In Jim Crow’s Pink Slip, scholar Leslie T. Fenwick, tapping seldom-seen transcripts from a series of 1971 U.S. Senate hearings on the topic, writes that the loss of Black educators post-Brown was “the most significant brain drain from the U.S. public education system that the nation has ever seen. It was so pervasive and destabilizing that, even more than half-century later, the nation’s public schools still have not recovered.”

While Black students now represent about 15 percent of K-12 enrollment, just 7 percent of teachers and 11 percent of principals are Black. Research shows that this dearth of Black educators has consequences: One 2018 study, for instance, found that Black students who had just one black teacher by third grade were 13 percent more likely to enroll in college. Those who had two were 32 percent more likely.

What’s more, Fenwick says, current threats over issues such as Critical Race Theory are cut from the same cloth as the threats that Black educators faced post-Brown.

74 contributor Greg Toppo spoke with Fenwick, an education policy professor and dean emerita of the School of Education at Howard University, about the Senate hearings, the backlash to Brown and ways to bring Black teachers back into the classroom.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Can you take us back to the moment when you first learned about this history?

Leslie T. Fenwick: I learned this history on my own as part of my disgust with a Politics of Education class that I was taking as a doctoral student. The professor decided that the class on the politics of education would not discuss Brown! Instead, we were going to start at a different point, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg decision [the 1971 decision that upheld busing to achieve integrated schools]. And I remember being outraged by that. If there’s any place where we should be unpacking Brown, it should be in that class. Additionally, the faculty member opened the class with this roster of statistics reflecting disparities in education between Blacks and whites, but I was concerned that there was no framing for these statistics, and that without the framing, there was kind of a tacit reinforcement of some racist assumptions about Blacks and intellectual and academic underachievement. So after class I marched to the library, almost in protest, saying to myself that I was going to bring back some statistics and facts to inform this faculty member about education disparities and also to make the case for why we should be discussing Brown. And as I’m looking for resources in the library — I’m literally in the stacks because this is before the Internet — I come across these Senate hearings on the displacement of Black principals. And I start reading them. And that’s where I learned about this history. I carried those transcripts around for quite some time, looking for someone to write the book that I ended up writing.

Those 1971 Senate hearings feel like a hidden history. Why are they not more widely known?

These [Senate hearing] transcripts have been cited at least 100 times in work by scholars and journalists, but no one has written in depth about the most prominent focus of the transcripts, which was Black educators’ superior academic credentials and professional experiences, and how they were replaced by lesser-qualified whites. I wasn’t expecting to find that. … This is the thrust of the hearings. And yet in all the work that cites the hearings, there’s not a focus on these Black educators’ exceptional academic credentials.

You paraphrase testimony from the hearings, writing that as school desegregation slowly played out post-Brown, “White principals and teachers became its direct beneficiaries, while Black educators were its primary prey.” Reading that, I wondered, “Who were the hunters?”

We’re talking about life in the 17 dual-system states, although outside of those states, there are jurisdictions that also have racially segregated schools. And we see, even in the North, this is happening too. But en masse, it’s happening in the 17 racially segregated states, from Delaware down to Florida, over to Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas, etc. And the hunters become governors, mayors, state legislatures — not individual legislators, but legislatures — and also locally elected officials: mayors, but also school superintendents and school boards. Remember, this is a time still after Brown of a lot of racial constriction. The customs of racism and Jim Crow are alive and well, which means that Blacks experience difficulty and barriers to voting. So that means local officials, school board members, superintendents in the states and jurisdictions where they are elected — and certainly state legislatures and governors [are involved]. And so without full voting rights extended to Blacks, those controlling the state and local levers of power and policy are almost all white and mainly committed to maintaining the segregationist hold on schools. And these are the individuals and entities that facilitate, through the use of state budgets and the use of state codes and statutes, the firing, dismissal and demotion of Black principals and teachers.

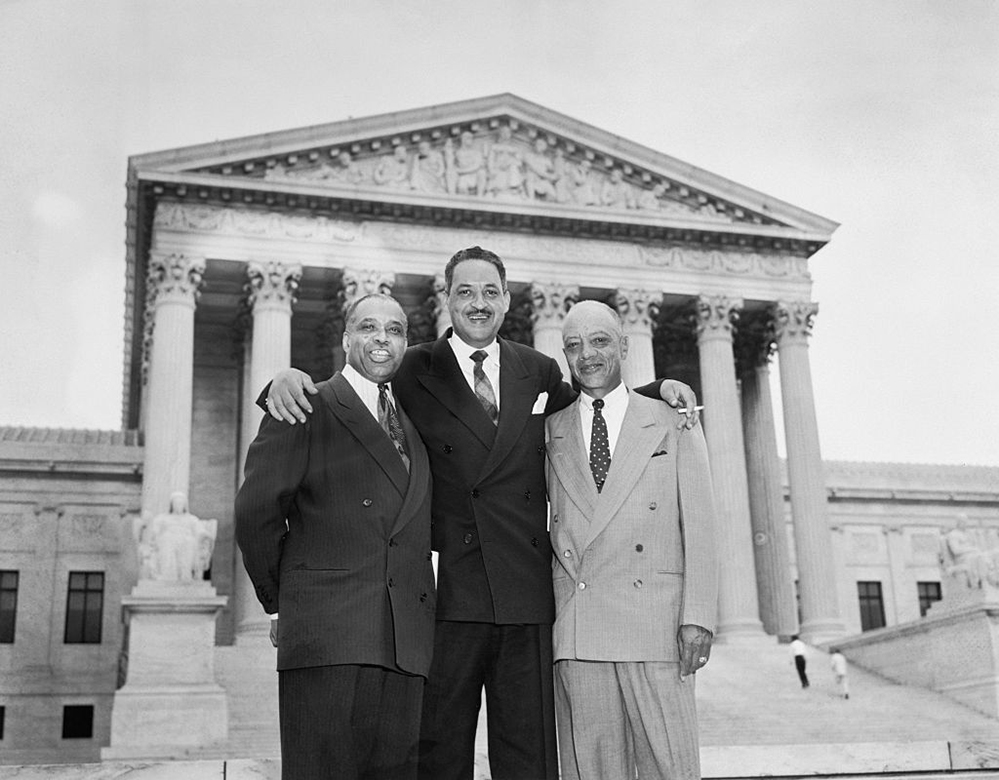

You write that Thurgood Marshall in 1955 noted that Black educators’ jobs needed to be protected. Did he and the legal team go into Brown with this possibility on their minds?

There was a series of cases that led up to Brown that were about disparities in paying Black and white teachers. Again, Black teachers with more credentials would make less money in the 17 dual-system states than white teachers with certificates. Thurgood Marshall and many of his team litigated those cases … Marshall and his team knew Black educator displacement was likely to happen. Remember, prior to Brown they’re going to Southern and border states, and they’re litigating all the cases around pay inequalities and voter registration. They knew the parameters of Jim Crow very well. In fact, early on, Marshall establishes the Teacher Information and Security Department of the NAACP to provide funding for legal support to the Black principals and teachers whom he thought would be illegally targeted and lose their jobs as a result of white backlash to Brown.

Do you give Marshall’s legal team any culpability for being naive in their strategy?

I don’t hold the Brown decision, nor the men who were the geniuses behind that decision, culpable. But what I do hold culpable is white resistance and the ability of local and state leaders to, in a swoop, use state statutes and budgets to support their segregationist agenda in the face of Brown, which would become the law of the land. Brown was right: There is no place in an American democracy for segregation. There is no reason Black citizens should not be able to access tax-supported institutions. There is no reason we should have, in this great country, racially segregated customs and laws. Brown was a great and brilliant decision. But there was powerful backlash to the decision that continued for at least 25 years. Sadly, I think it’s still continuing. In fact, the current death threats against superintendents who have initiated race equity initiatives, the physical intimidation of school board members, the threats against teachers and to burn books — when I was writing Jim Crow’s Pink Slip and then looking at the current news, it’s the same script, and that really shocks me.

You’ve anticipated my next question: Reading your book, I felt like the conversations we’re seeing now about CRT and pushing students away from subjects that make them uncomfortable are a direct result of this history. Can you reflect on that?

I wrote the book to push against this myth that there are not enough Black teachers, because after Brown, Blacks fled the profession to pursue fields and careers that were previously unavailable. Well, the history doesn’t say that, nor do U.S. Labor Department statistics show that. And we’re still living with this history: Of the nation’s 3.2 million teachers, about 7 percent are Black. About 11 percent of the nation’s 93,000 principals are Black. And less than 3 percent of the nation’s almost 14,000 superintendents are Black. And so I ask myself, and I ask the reader: Where would we be if these generations of Black educators, who were more credentialed than their white peers who replaced them, who had a personal commitment to end anti-Black racism, who had put their lives on the line to lead voter-rights campaigns in their communities, who were committed to a representative democracy — what if they hadn’t been fired? What if they had been in place during a critical time in our nation’s history and were part of building integrated schools? Where might we be as a nation now?

As you write, they weren’t just teaching, they were also politically active.

Many of these principals and teachers were establishing voting-rights campaigns in their locales. They were establishing NAACP chapters. This was their activism. And in other literature, they’re called community activists and community leaders. But more specifically, their community activism was devoted to helping Blacks get registered to vote and working with the NAACP on lots of equality issues. And so they were threats. These Black educators were cornerstones of political activism even in the face of threats to their own lives.

So in 2022, if the dearth of Black teachers isn’t a recruitment issue, what’s the solution?

When the Nixon administration was pressured about this as a result of the Senate hearings in the ‘70s, the response of the administration was not pro-integration. They designated $3.2 million to the retraining of Black educators for integrated schools. Well, Black educators didn’t need retraining. On a near one-to-one basis, they were more credentialed than the white educators who replaced them. So, the Nixon administration’s retraining investment is literally used to usher Black principals and teachers out of the profession. I go into great, great detail and cite the federal documents that show how they were ushered out of the field. So we need a counter-investment, and particularly in institutions that produce large percentages or numbers of Black and other educators of color. I always say that even in 2022, HBCUs, which are 3 percent of the nation’s colleges and universities, are producing 50 percent of the nation’s Black teachers — and two HSIs (Hispanic Serving Institutions), one in Texas and one in Florida, produce 90 percent of the nation’s Latinx teachers. So we do need some financial investment in the institutions that are producing teachers of color. And we need to examine, I think, any other structural barriers preventing Black and other teachers of color from entering the profession, either as teacher education students or novice teachers.

It strikes me that it’s such a vicious cycle: If you’re a Black student and don’t see Black teachers, your incentive to do this work, to see yourself in this job, just gets reduced. And that feeds into an ongoing cycle.

We know that academic and social benefits accrue to African-American, Hispanic/Latinx students when they’re in highly diverse-staffed schools. They’re less likely to be expelled, less likely to be misplaced in special education, more likely to graduate high school, more likely to apply for college, have reading and math achievement that’s excellent in certain grades. And so we are losing out on some academic achievement, not just for Black and brown students, but possibly for all students. I say in the book, over and over again, that all children benefit from having diverse models of intellectual authority.

See previous 74 Interviews: professor Daryl Scott on teaching the history of race in America; author Amanda Ripley on losing trust in schools; professor Seth Gershenson on the importance of teacher diversity; author Paul Tough on higher education myths; and the full archive of 74 interviews.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter