How Texas Lawmakers Gutted Civics

A little-noticed casualty of the culture wars in the Lone Star State has been the training students receive to participate in American democracy

The defining experience of Jordan Zamora-Garcia’s high school career — a hands-on group project in civics class that spurred a new city ordinance in his Austin suburb — would now violate Texas law.

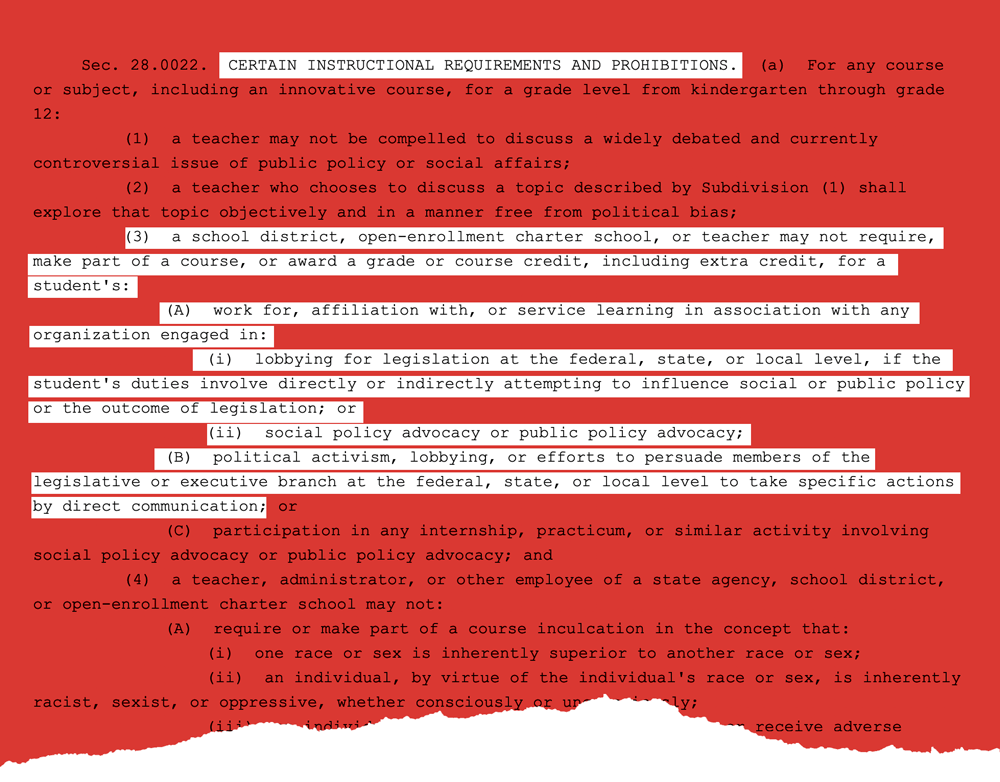

Since state legislators in 2021 passed a ban on lessons teaching that any one group is “inherently racist, sexist or oppressive,” one unprecedented provision tucked into the bill has triggered a massive fallout for civics education statewide.

A brief clause on Page 8 of the legislation outlawed all assignments involving “direct communication” between students and their federal, state or local officials. Educators could no longer ask students to get involved in the political process, even if they let youth decide for themselves what side of an issue to advocate for — short-circuiting the training young Texans receive to participate in democracy itself.

Zamora-Garcia’s 2017 project to add student advisors to the City Council, and others like it involving research and meetings with elected representatives, would stand in direct violation.

Since 2021, 18 states have passed laws restricting teachings on race and gender. But Texas is the only one nationwide to suppress students’ interactions with elected officials in class projects, according to researchers at the free expression advocacy group PEN America.

Practically overnight, a growing movement to engage Texas students in real-world civics lessons evaporated. Teachers canceled time-honored assignments, districts reversed expansion plans with a celebrated civics education provider and a bill promoting student civics projects that received bipartisan support in 2019 was suddenly dead in the water.

“By the time we got to 2021, civics was the latest weapon in the culture wars,” state Rep. James Talarico, sponsor of that now-defunct bill, told The 74.

Texas does require high schoolers to take a semester of government and a semester of economics, and is one of 38 states nationwide that mandates at least a semester of civics. But students told The 74 the courses typically rely on book learning and memorization.

Talarico, a former middle school teacher and the Texas legislature’s youngest member, came into office during a statewide surge in momentum to deepen civics education. A 2018 study out of the University of Texas highlighted dismal levels of political participation — the state was 44th in voter registration and 47th in voter turnout — and Democrats and Republicans alike were motivated to reverse the trend. Meanwhile, academic research found lessons directly involving students in government could activate future civic engagement.

So when the freshman legislator proposed that all high schoolers in the state learn civics with a project-based component addressing “an issue that is relevant to the students,” colleagues on both sides of the aisle stamped their approval as the bill sailed through the House. Although the legislation then stalled in the Senate, Talarico said he came away “very optimistic” the policy would become law next session.

But in the two years before the next legislative session, he watched as the political tides turned. Flashpoint issues like George Floyd’s murder and the Jan. 6 insurrection brought on a “disagreement over democracy itself,” he said. And when his conservative colleagues passed a 2021 bill limiting school lessons on race and gender, he mourned as a few brief clauses dashed all his hopes for project-based civics.

“Students are now banned from advocating for something like a stop sign in front of their school,” Talarico said.

A battle over civics

The sections of the 2021 law limiting civic engagement pull directly from model legislation authored by the conservative scholar Stanley Kurtz, whose extensive writings seek to link an approach called “action civics” — what he calls “woke civics” — with leftist activism and critical race theory. Critical race theory is a scholarly framework examining how racism is embedded in America’s legal and social institutions, but became a right-wing catch-all term for teachings on race in early 2021.

Kurtz argues the practice is a form of political “indoctrination” under the “deceptively soothing” heading of civics, a cause long celebrated on both the right and the left.

The action civics model was popularized by the nonprofit Generation Citizen and is used in over a thousand classrooms across at least eight states. It teaches students about government by having them pick a local issue, research it and present their findings to officials.

The central philosophy is that “students learn civics best by doing civics,” Generation Citizen Policy Director Andrew Wilkes said.

Generation Citizen’s method has been studied by several academic researchers who found participants experienced boosted civic knowledge and improvements in related academic areas like history and English.

Kurtz, however, contends the projects “tilt overwhelmingly to the left.”

“Political protest and lobbying ought to be done by students outside of school hours, independently of any class projects or grades,” he said in an email to The 74.

Civics experts, however, argued otherwise.

The notion that “it’s activism happening in classrooms … that’s just so far from the truth,” said Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University in Boston.

Rep. Steve Toth and Sen. Bryan Hughes, the GOP lawmakers who sponsored the 2021 anti-CRT legislation, did not respond to requests for comment.

The 74 reviewed over three dozen action civics projects in Texas from before the 2021 legislation and found that the vast majority dealt with hyperlocal, nonpartisan issues.

Students most often took up causes like bullying, youth vaping, movie nights in the park or bringing back student newspapers. A handful in Austin and nearby Elgin could be considered progressive, including projects dealing with gun control or school admissions prioritizing diversity, topics educators said students selected based on their own interests.

Under the 2021 law, all of those projects now must avoid contact with elected officials. The restrictions have resulted in initiatives more contained to schools themselves like advocacy for less-crowded hallways or longer lunch periods, educators said.

“This particular legislation … ties [students’] hands as to how involved they can get while in high school,” said Armando Orduña, the Houston executive director of Latinos for Education.

His own political awakening, he said, came three decades ago growing up in Texas when a teacher assigned him 10 hours of volunteering on a political campaign of his choice. He opted to work on the 1991 Houston mayoral campaign of Sylvester Turner, then a young state representative who lost his bid that year but went on to become the city’s mayor in 2016.

“Back then, the attitude was how to fight teenage apathy regarding politics and now it’s quite the other way around,” Orduña said. Now politicians are working to “tamp down the next generation of leaders.”

Young progressives have become a considerable force in American politics, fueling recent electoral wins in the Wisconsin Supreme Court, the Chicago mayoral race and a base-rousing standoff in the Tennessee legislature. In the eyes of some members of the GOP, their activism is seen as a threat.

‘Everything got turned upside down’

Though some project-based civics lessons in Texas continue with a pared-down scope, others have disappeared altogether.

One school district north of Dallas decided “out of an abundance of caution” to reverse years of precedent and stop offering course credit to students involved in a well-regarded national civic engagement program, The Texas Tribune first reported.

And Generation Citizen, too, has seen its footprint in Texas dwindle.

After a 2017 launch in the state, the organization underwent several years of steady growth, with more than a half dozen districts using its programming or curricula. At the time, districts in San Antonio, north Texas, the Rio Grande Valley and several rural regions had expressed interest in beginning programming, former regional director Meredith Stefos Norris said. She spent most of her days criss-crossing the sprawling state meeting with interested school leaders. Austin schools expanded their contract with the nonprofit to $58,000, according to records The 74 obtained from the district through a Freedom of Information request. And Dallas said it wanted to bring Generation Citizen programming to every high schooler in its 153,000-student district, Norris said.

“It felt at the time that we were just going to keep going and keep growing and there was no reason that we weren’t going to be a statewide organization,” the former Texas director said.

Then came the 2021 legislative session and “everything got turned upside down,” said Megan Brandon, Generation Citizen’s current Texas program director. It zapped their efforts and districts backed out of partnerships.

The organization now primarily works with just three Texas districts, including an updated contract with Austin schools for $3,000 — a tiny sliver of the sum from a few years prior. The other two are Bastrop Independent School District and Elgin Independent School District.

Meanwhile, across the state’s northern border in Oklahoma, where Generation Citizen also operates, lawmakers passed a classroom censorship bill around issues of race and gender, but one that did not limit students’ contact with elected officials. The organization has been able to maintain all its programs while “following the letter of the law,” Oklahoma director Amy Curran said.

“This isn’t organizing about big culture wars, national stuff,” she said. “This is, literally, the sidewalks are unsafe around our school.”

Brandon, a former social studies teacher herself, grieves not just for the Texas branch of her organization, where the nature of the projects are similar, but for the youth in her state. Her former students in Bastrop ISD outside Austin, most of whom did not have parents who attended college, never had access to civic engagement opportunities before her class, she said.

“Students in Texas need civics more than students in many other states,” she said. “It feels like we’re going backwards in time.”

Opportunity cost

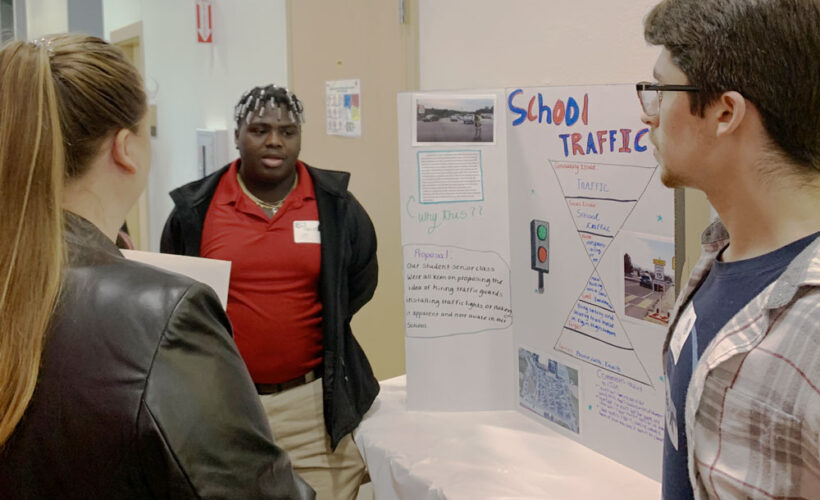

Zamora-Garcia remembers striding to the dais of the Bastrop City Council in 2017 with seven of his peers — the boys clad in too-big blazers and bow ties, the girls in dresses and laced-up heels. For a project they began in Brandon’s civics class, the team sought to boost youth voices in their local government. After meeting with officials, researching models and drawing up bylaws, the students eventually made history by passing a city ordinance in the Austin suburb to add student advisors to the City Council.

“It made me feel more important and more involved, actually being able to have a voice that can make a change,” said Zamora-Garcia, now a junior at Texas State University studying business.

The course activated his potential in class and in the community, he said. Before the experience, school had felt more like being a “cog in a machine,” he said.

Mabel Zhu, who took the same class two years later, said the experience was “life-changing,” igniting her passion for civic engagement for years to come.

After the class, she began working with a local nonprofit, then organized a youth summit bringing awareness to the issues of mental health and substance abuse. She eventually joined the Youth Advisory Council that Zamora-Garcia and his classmates helped launch and worked with the Cultural Arts Board to put up a new mural that will define her city’s downtown space for years to come. A waving flag on the painting proclaims, “The future is ours!”

“Without [the class], I wouldn’t have been able to make such an impact within my community,” Zhu said.

The loss of such opportunities are what Rep. Talarico calls the unseen “opportunity cost” of the culture wars.

“What are we missing out on that we could be doing if we weren’t playing political games with our students’ education?” the Democratic lawmaker asked.

Many students in Texas either learn how to engage with the political system in school or not at all, teachers said. Kyle Olson, an educator at an East Austin high school that serves predominantly immigrant families, taught his students that, as constituents, they could write letters to their elected representatives.

“They didn’t know that that was even something that was possible,” he said.

Neutering those lessons flies in the face of American democracy itself, argues Alexander Pope, who leads the Institute for Public Affairs and Civic Engagement at Maryland’s Salisbury University.

“Part of the job that schools have in this country is to help prepare people for democracy,” he said. “The idea that, in a representative democracy, you’re going to literally ban … people from writing their elected representatives is just backward.”

The risk, believes Tufts’s Kawashima-Ginsberg, is that a generation of Texans may grow up with a stunted sense of citizenship.

“It’s going to really damage their idea of what democracy is,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter