Sometimes the Outcome Is the Equity: Why It’s Critical to Prepare Students of Color to Do Well on Standardized Tests — Even If You’re Not a Fan

The release of the Nation’s Report Card last week was the exclamation point following a long line of 2018-19 state exam results that came out across the country in the past few months. There are three things I expect to hear every year around this time:

● We don’t even need to see the results. You can predict which schools will have low proficiency rates based on the poverty rates and demographics of the students who go to these schools.

● These tests were designed by eugenicists. So, of course black and brown students fail.

● Test results don’t tell the whole story.

Honestly, I do not fully disagree with any of these. I fundamentally believe that demographics do not have to be destiny. But with some exceptions, you would do well as a gambler if you put your money on schools having proficiency rates well below 40 percent in schools serving students in low-income, minority communities. And I get that the origins of standardized testing are suspect. Test results are also poor indicators of how much teachers love and work hard for their students, and they are admittedly not the be-all, end-all of measuring this work. But when I hear people dismissing standardized test results outright, I become very concerned.

I become very concerned because I know that I want my children to pass the test. I do not care that it is an imperfect measure. I do not care if it is culturally biased. I do not care whether the test is being administered as a backhanded way to punish teachers. I just know that I want my children to pass. I want my state to do well. And as a teacher, I really wanted my students to pass, too.

My mom wanted the same for me. Back when New York City used CLOZE passages for their reading exams, I cannot tell you how many of these workbooks my mother threw in front of me to practice. As an immigrant and a single mother struggling financially to raise her children in Brooklyn, she understood what so many parents like her fundamentally understood: I was being measured on a scale that required me to work twice as hard to get half as far. So, I needed to not just pass, but excel on this scale and every other scale they put in front of me. But I often wonder if we fully understand the equity issues at stake when it comes to testing.

When I refer to equity and testing, I am not talking about biased test questions or the results that show that low-income and students of color disproportionately do poorly on these exams. Instead, I am referring to equity of outcomes. I presume that most of us believe that education ought to transform opportunities for children by breaking cycles of poverty. But at some point, the outcome is the opportunity. We should care about how students do on exams regardless of the inherent imperfections of these tests. Why? Because lawyers have to take the LSAT and pass the bar exam. Doctors have to take the MCAT, USMLEs and board exams. Engineers, nurses and numerous other professions still use tests as barriers for access.

Whether these barriers are fair is not my concern. My concern is that we should not live in a world where only the students who can afford expensive test prep programs have access to the practical strategies they need to succeed on these exams. I am unapologetic in my belief that we owe it to our students to teach them how to be successful on the various types of tests they will face academically, professionally and in life. And we are simply not doing this.

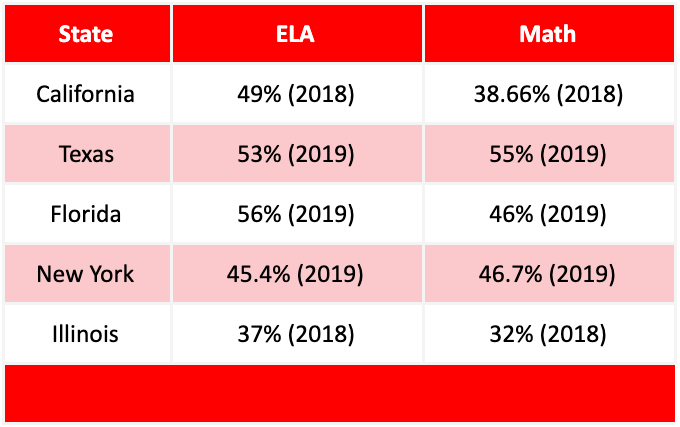

Examining the most recently available eighth-grade proficiency rates for children tested in the five most populous states demonstrates this failure:

Eighth-grade proficiency rates

An important note here for those who take results like this and extract all sorts of inappropriate conclusions: These results have a very specific meaning. They tell us whether students tested as “proficient” on their statewide standardized exams. It is important to use precise language here. You cannot accurately conclude that 47 percent of Texas eighth-graders cannot read, or even conclude that they cannot read at grade level. Call it what it is so we can be clear about the two problems we are dealing with. The first problem: Our proficiency rates on standardized exams are unacceptably low. And second: Despite these rates being unacceptably low, there is not enough outrage for the persistence of these dismal proficiency rates. None of these states reach a 60 percent proficiency rate in either math or English Language Arts. It does not take special expertise to predict that these data will look even more troublesome when we disaggregate them by race, special education status, socioeconomic status and English Language Learner status. But it seems premature to even talk about the achievement gap in proficiency rates when we are struggling so much to achieve proficiency, period.

My work supporting schools across the country has led me to understand that there are some educators who exhibit a high degree of reluctance, struggle and outright disdain toward testing, test prep, anything else that feels inauthentically “testy.” But ensuring that students are prepared to be proficient on standardized exams should not require them to feel like sellouts. It is a quintessential false-choice scenario to feel as if educators must choose between giving students the tools and strategies they need to conquer these exams or engaging students in rigorous and relevant content.

It turns out that hacking test prep with critical thinking is not only feasible but necessary. Because let’s be real: If there were such a thing as “teaching to the test,” we would have cracked that code by now. Whether your state uses the PARCC, SBAC, STAAR, AzMerit, SOL (quite the choice of initials there, Virginia) or a different assessment, rote memorization and spoon-fed learning are not going to prepare students for success on these exams like they did with my CLOZE exam back in the day. Here’s an example of why drill-and-kill doesn’t work:

A sandwich shop offers a 15% discount when a customer spends at least $75. The shop sells sandwiches for $8.25 each and cookies for $1.45 each.

Juliana buys 8 sandwiches.

What is the least number of cookies that Juliana can buy and still get the discount?

This question, adapted from a real-life standardized exam, is a perfect example of why “teaching to the test” is impossible. To get this question right, a student needs to understand the purpose of five different numbers, avoid being fooled by the 15% figure, which is not relevant to the problem, understand how inequalities are set up, know how to multiply decimals, subtract whole numbers, and divide decimals. And if that isn’t enough, the student must recognize that Juliana cannot buy 6.2 cookies, so she will have to buy 7 in order to get the discount. Making this even harder, this is a grid item response where students need to enter in “7” as their answer. In other words, this is not one of those multiple-choice questions where you can guess or use process-of-elimination to solve.

Students need critical thinking to apply their knowledge and exercise tons of logical reasoning to work through tricky multi-step and multiple-choice questions. Students also need critical thinking as an essential 21st century skill. And all students, particularly students of color, students in poverty and linguistically diverse students, deserve to go to a school that prepares them to compete in a world that often requires them to work twice as hard to get half as far. Approaching test preparation with this lens is an essential prerequisite for going beyond mere opportunity and toward equitable outcomes for all students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter