Otero: Strong Education Leaders Are Key to Advancing Racial Justice in the Nation’s Ongoing Fight for Equity

As the nation reels, once again, from the murder of a black man at the hands of an officer sworn to protect the public, Americans are yearning for solutions that enable us to live up to our ideals. One of the most promising lies within our schools.

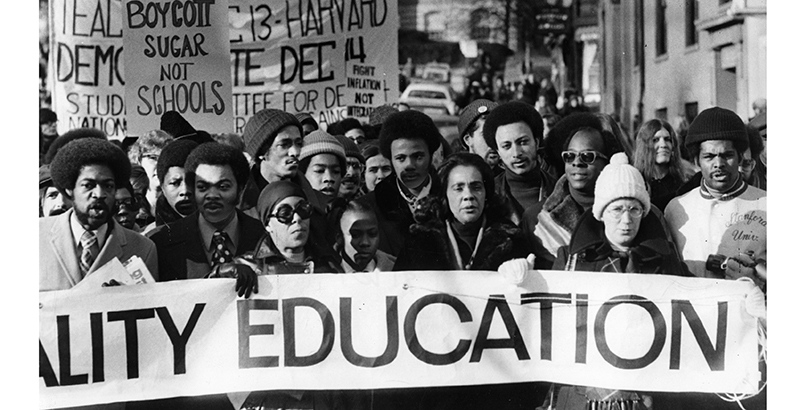

Education has long been intertwined with racial equity and central to greater inclusion for black Americans. Decades before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus or Martin Luther King Jr. led nonviolent protests around the country, the NAACP was fighting to desegregate schools. Thurgood Marshall and other civil rights leaders — who often identified first and foremost as teachers — realized that “separate but equal” was inherently unequal and, in fact, schools powerfully exemplified the racial prejudice that pervaded society.

When policymakers sought to rectify segregation, they looked to education. Head Start and Title I became cornerstones in the fight for civil rights. The president who signed those laws in 1965 was Lyndon Johnson, whose early experience teaching in a low-income, rural Mexican community in south Texas shaped his view of education and opportunity. In the decades since, national leaders from both major political parties and all sectors of society have again and again come together to try to transform schools into agents of opportunity for low-income children and children of color.

Throughout my lifetime, I have seen many leaders pursue educational leadership as a means to heal our racial divides. Therefore, I am compelled to step forward in this moment and share two fundamental truths I believe deeply. First, that an equitable educational system is the foundation for racial justice. Second, that equity-oriented education leaders are uniquely well positioned to help heal the wounds being laid bare today.

Aleesia Johnson, superintendent of Indianapolis Public Schools, for example, characterizes her service as an educator and educational administrator as an extension of the work her grandfather Anthony Brooks Sr. did for racial justice. “My grandfather wasn’t only an educator, he was a social justice warrior in our community,” she said in an interview last year with the nonprofit organization Chiefs for Change.

He integrated the lunch counter and he went to jail for his beliefs in equality for the African-American community. “The example he set fighting for the rights of people who look like me has influenced all the choices I’ve made,” she said.

Jason Kamras, who leads Richmond Public Schools, uses his platform to make instructional decisions that help empower students of color. Last year, he invited historians, civil rights leaders, clergy and others to develop the REAL Richmond curriculum to teach high school students about the unvarnished history of the Southern city, with its deeply checkered racial past. Recently, the district selected an English Language Arts curriculum designed by an organization with a strong commitment to anti-racist education.

And Janice Jackson, CEO of Chicago Public Schools, who has led her district to unprecedented academic gains, recently released a toolkit called “Say Their Names” to “help foster productive conversations about race.” Chicago Public Schools was the first school district in the nation to add the New York Times’s 1619 Project, a project aimed at reframing American history by re-examining the legacy of slavery, to the high school social studies curriculum.

Strong leadership is the foundation of transformational policy and programs. The latter simply cannot work without the former.

To be sure, strong education leaders alone will not solve racism or police brutality. First, our criminal justice and policing systems must be changed to ensure that all communities and all people, regardless of race, are treated with dignity and respect and receive the protection and support they deserve. Second, inequitable school funding formulas and entrenched educational policies and cultures can prevent innovative and forward-thinking education leaders from realizing their visions. And third, broader policy changes in economic, housing and health care policy are all necessary to confront the scourge of structural racism. We need strong leaders in schools and outside of them.

But cultivating and deploying strong education leaders who are motivated by racial justice, who are able to acknowledge the pain of the moment, to teach all students about the history that has led us here, and to model empathy and compassion can and should be an important part of addressing these issues over the long term. Marshall presciently warned after the Brown v. Board of Education verdict came down that “the fight has just begun” — and we are still in the fight for equity today. I hope and believe that if we educate more children in schools and districts run by leaders who affirm their identity and are motivated by equity, the fight will advance more rapidly.

Mildred Otero is senior vice president, national impact, for Leadership for Educational Equity. She previously served as chief education counsel for the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter