Why I Wrote ‘Thinking Like a Lawyer’: Because Teaching Critical Thinking to All Students Paves a Path to Racial Justice

As a “poorly behaved” Black boy in Brooklyn, New York, on free and reduced-priced lunch whose parents were immigrants and whose father was incarcerated for selling drugs, I had the rare experience of being selected for a gifted and talented program starting in second grade.

My first-grade class was all about drill-and-kill, low-level tasks with no complexity. Second grade was radically different. From creating my own fairy tales to designing our own science experiments, I learned what a separate and unequal education was at an early age. This was a racial justice issue.

I saw the same racial justice issue play out years later in my first year of teaching algebra and geometry in Washington, D.C. One on hand, my students had so much fire. I was so impressed by how well they thought on their toes, their impressive ability to size up people in seconds, and how they were so creative in optimizing constraints to get the most of what they had. At the same time, they struggled academically. Many were at least a grade level behind. And most of my “advanced” learners were placed there simply because they were well-behaved.

Like so many teachers still do today, my response to their academic struggles was the wrong one even though it felt like it was done out of love: I dumbed it down. Fast-forward to today, where there finally seems to be a broad consensus that yes, Black lives do matter. But if Black lives matter, shouldn’t Black minds matter too?

My teaching practices then and the practices of so many educators across the nation today raise serious issues of racial justice in education that play out in classrooms daily. From teachers assigning the easiest version of the test, skipping the tough word problems because “these kids can’t,” and teaching to the mythical middle student so no one gets too far behind — even if that means students will not receive work at their grade level — leaving genius on the table was and is far too common.

My teaching philosophy changed in 2004 when I spent a day observing middle schoolers at Georgetown Day School in November of my first year of teaching. This private school, where annual tuition today exceeds $40,000, was different from any school I had ever seen. I met with the principal that morning before my observations began, and as we walked through the hallway, a kindergarten student said, “Hi, Bill.” I thought to myself, “I’m not Bill. Who the hell is Bill?” And the principal replied to her, “Hi, good morning.” Calling teachers by their first name went against everything I was taught about the power dynamics of schools.

But this power was less about titles and more about students having power to do the heavy lifting in their own learning. Every class I attended, including classes for struggling learners, put students at the center. Teachers pushed students to engage in endless amounts of productive struggle. Geometry students were making up their own proofs. Algebra students were analyzing an equation done incorrectly in two different ways and debating over which wrong answer was more “right.” I watched these students speak much more than their teachers. And I recognized something: These students were not in any way better or smarter than my students. The only difference is that here, the adults taught as if students are capable of doing absolutely anything they set their minds to.

The critical thinking gap really hit me when I started practicing law in 2013. As I’m serving on several community and nonprofit boards, including the Nevada STEM Coalition, I’m listening to lots of conversations about the future of work. Every keynote speaker, every education op-ed, every business community member was Paul Revere-ing the need to equip young people with critical thinking. How else will they solve problems unseen, in career fields that do not exist, using technologies that have not yet been created?

But the “evidence” school systems presented of their efforts to meet this need revealed even more racial justice issues. The students with critical thinking access during the regular school day attended incredible, but highly selective magnet, gifted and career and technical education programs that served only a tiny fraction of students. After school, the robotics club, Model United Nations and mock trial teams were also doing a great job of teaching critical thinking. But the day-to-day experience of so many students did not provide deeper learning experiences, especially for students attending schools serving high numbers of students of color living in low-income communities.

This is a massive racial justice issue because critical thinking should not and cannot be a luxury good. But how do we teach critical thinking to all students? Speaking to hundreds of teachers and education leaders helped me understand three reasons students who are academically behind their peers, students with special needs and emerging bilinguals are so frequently denied access to critical thinking instruction. The first cause of the critical thinking gap is the belief gap. There are simply too many educators who do not truly believe all students can handle rigorous content. Second, there’s an issue of teacher efficacy. In other words, even teachers who believe all students can think critically do not necessarily believe they themselves can make this a reality. Last but not least, even when these two prerequisites are fulfilled, teachers with unshakeable beliefs about our students’ unlimited potential, who also believe in their own potential, struggle to find the time, tools and resources to actually deliver on critical thinking instruction as a priority.

But in a world where our students need to be extremely adaptable and agile as a key to future-readiness, thinking critically across contexts is crucial. How can we do this?

My “aha” moment occurred when I made the questionable decision to go to law school at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’s part-time evening program while teaching full time as a math teacher in Las Vegas. Don’t. Do. That. But something interesting happened there. As a child, I was never chosen as student of the month, or even of the day. Yet I graduated at the top of my law school class. Why? Because law school was not about memorizing a set of facts. It was about “Thinking Like a Lawyer.” Looking at different perspectives, asking questions to get information, making claims and backing them up with evidence. It didn’t matter the discipline, because if you worked on a case involving the construction industry, you had to “learn how to learn” about esoteric construction terms. Same for intellectual property or federal income tax law. I realized that these were the same critical thinking skills and dispositions all students needed. So why wait until law school to introduce them?

This was not about teaching a generation of students to be attorneys. It was about revolutionizing education by obsessing over the practical. The “Thinking Like a Lawyer” framework was a powerful “how” resource for my math class. My first question on an exam on probability was once, “If you were a gambler in Las Vegas, would you prefer to know your probability of success in a table game or the odds? What if you were the casino?” Students are motivated by issues of fairness and justice. And it turns out that getting students to analyze challenging questions from different perspectives has a very different kind of energy when they start to realize that this “street smart” label they are so often given is actually just “smart.”

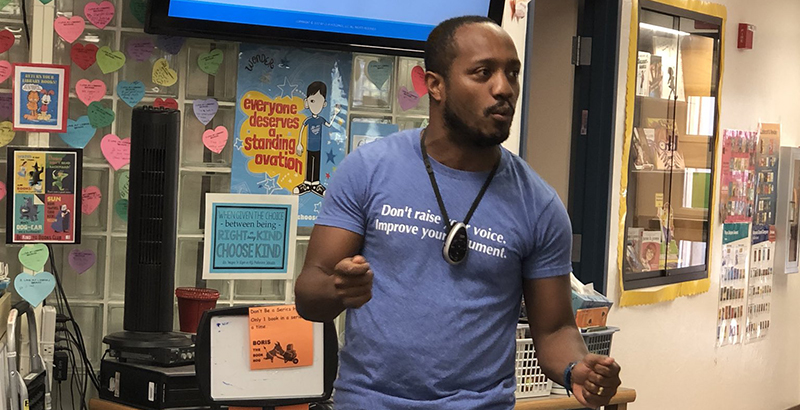

Five years later, the “Thinking Like a Lawyer” framework is taking off through my work with thinkLaw, an award-winning program used by educators across the country. We focus on curriculum based on real-life legal cases in upper grades, fairy tales and nursery rhymes in lower grades (because there are a ton of shady characters in children’s stories), and professional development for teachers and parents for powerful but practical critical thinking workshops that help educators make the 21st century shift from asking “what” and “how to” to asking “why” and “what if.”

There were so many ways to leverage this framework into day-to-day instruction, from reimagining test prep to using critical thinking as a tool for shifting our thinking on classroom management, that it needed a book. With this practical “how to” guide to overcome the very real barriers to critical thinking access for all students, we can be much closer to a world where critical thinking is no longer a luxury good. And if we can give our students the tools to not just analyze the world the way it is but also question the way it ought to be, we can make real strides toward fighting for educational justice and racial justice simultaneously, as we must.

Colin Seale is a critical thinking expert, achievement-gap-closing educator and attorney who founded thinkLaw — an award-winning program that helps educators teach critical thinking to all students using real-life legal cases and other Socratic and powerful inquiry strategies. He is a national speaker who contributes to Forbes and Education Post. Seale is the author of Thinking Like a Lawyer: A Framework for Teaching Critical Thinking to All Students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter