A Year After Nationwide Protests, District Promises for Racial Equity — Juneteenth Gains Legal Popularity, but Misses Classroom Recognition

Updated, June 17

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Texas 8th-grader Ernest Toledo said he’s learned and relearned Texas history throughout elementary and middle school, yet has never been taught a word about Juneteenth, an event in the Lone Star State many consider the first independence day for Black Americans.

“We should talk about it,” Toledo said.

After the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd sparked massive racial justice protests last year, state and city governments — and many private companies — rushed to recognize June 19 as a holiday for the first time. While the long-sought initiative has gained considerable steam, on the eve of Juneteenth a year later, many students, educators and parents are still wondering when it will make it into their state’s social studies curricula.

Today, 48 states and D.C. recognize the date formally as a day of remembrance or a holiday, and this week, President Joe Biden signed legislation making Juneteenth the nation’s 12th federal holiday after both both the Senate and the House approved the measure in a rare show of bipartisanship. Of the nation’s 10 largest public school districts, nine do not recognize Juneteenth in their calendars, although their school year ends for students in May or early June. New York City will formally close schools for Junteenth beginning in 2022, and Chicago Public Schools may follow suit should Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker sign a recently passed bill to recognize it as a state holiday.

Given its omission from most history lessons, Juneteenth celebrations in recent years mark the first time many Americans learned about that date in 1865, when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas were informed of their emancipation. Their liberation came more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation and two months after the end of the Civil War. 2021 will be the first year Galveston will celebrate Juneteenth as an official city holiday, 156 years later, although it’s been a proud tradition for Black residents of that city for generations.

Former U.S. education secretary John King, who recently wrote about living 25 miles away from where his great-grandfather was enslaved in Maryland, put the growing awareness of Juneteenth into the larger context — and increasingly fraught debate — of teaching in greater depth about America’s racist past.

“We have a responsibility to struggle for an America that is more true to the promise of equality of opportunity, and a critical part of that struggle is ensuring that we tell the full story of our history in our social studies curriculum,” King told The 74.

Juneteenth in the classroom

María Rocha grew up about 250 miles west of Galveston and now teaches sixth-graders at Mark Twain Dual Language Academy in her home district, San Antonio Independent School District. She excitedly shares details of this year’s Juneteenth musical celebration in town and excerpts from her own spoken word piece on the need to change history textbooks, though she can’t recall a time she or her colleagues included the day as a part of their social studies instruction.

When asked what elements of culturally significant history she incorporates in her classroom, she shares that she sticks to what’s outlined in Texas state social studies curricula.

“I want to be that teacher that has no limits to what she can say, but you know, unfortunately, our jobs are on the line with what we say and do,” she said.

Rocha’s concerns echo those of many educators facing legislation that can restrict their ability to touch on race-related content in the classroom. About 20 states are in the midst of passing such legislation, aimed at curbing antiracism training and critical race theory in schools. Just signed by Gov. Greg Abbott, Texas’s iteration also prohibits students from receiving course credit for political activism, or work with policy advocacy organizations on any issue (even, for example, service learning). In Tennessee, school funds can be withheld if teachers link historical events to institutional racism.

Without state or district-provided support, some educators have taken it upon themselves to make Juneteenth a part of their Civil War units. For years, artist and social studies teacher Diane Isaac has begun her Juneteenth lessons at Curtis High School on Staten Island with a gallery-walk of primary source documents, images, and first-person accounts from the 1860s. She leaves materials on the walls all week, and invites her 11th-graders to go back and respond to other students’ reactions. On the first day of their Juneteenth lesson, students come together for a conversation about Frederick Douglass’s 1852 speech “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July”.

“I think it frames the Juneteenth celebration, because he’s pointing out that for African Americans, this concept of freedom and this jubilation, this celebration of American independence, did not apply to them,” Isaac said.

For Isaac, incorporating Juneteenth in her Civil War unit was never a question of why. It was a question of how she could make it a part of a bigger conversation in her school and community.

“I’ve had conversations with many of my colleagues who say, the Civil War, we’ll teach that in maybe one or two lessons; Reconstruction, one lesson; slavery, maybe two or three lessons,” she said. “In all of a week to a week and a half, the lived experience of African Americans is flown by. It’s narrowed down to a PowerPoint presentation, which may include some primary source documents, but there’s no real depth and I felt that I needed to provide that depth.”

Six years ago, Isaac shifted to teaching U.S. history to upper high school students. She decided then that she wanted to focus on “the histories of Black and brown people, the histories that were not highlighted”. Teaching Juneteenth, for her, is just one example of that practice in action.

A former social studies teacher himself, John King says Juneteenth is one chapter in a much greater story about the oppression and triumphs of Black Americans and other historically excluded racial groups. King, who is now running for governor in Maryland, said he regularly incorporated Juneteenth as a part of his Civil War and Reconstruction teachings.

“We should be advocating for inclusion of the study of the institution of slavery, resistance to Reconstruction, emergence of Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow, history of Japanese-American internment — we have to include all of those things, because that is the truth of the story. We also, at the same time, should be telling the story of the first Black elected officials during Reconstruction, and we should be telling the story about African Americans’ resistance throughout,” King said.

Even some smaller, predominantly white districts are in pursuit of a similar, intentional approach to acknowledging Juneteenth. Administrators from western Massachusetts to upstate New York now mark it as a school holiday and provide resources for educators looking to revamp their curricula.

Chicopee Public Schools will recognize Juneteenth as a district holiday beginning in 2022. District leaders have given out resources to elementary, middle, and high school teachers to support their new lessons on Juneteenth this year.

“We’re trying to be a more equitable, diverse, and inclusive school district. This is not just a holiday for Black people. This is a part of American history,” said Alvin Morton, assistant superintendent for student support services in the roughly 6,800-student Massachusetts district.

In Rhinebeck, a town of about 7,500 nestled in New York’s Hudson Valley, schools will close on June 18 in honor of the holiday. All week, Bulkeley Middle School is recognizing the significance of Juneteenth, starting with classroom lessons on its history. Seventh-grade social studies teacher Henry Frischknecht coordinated grade-wide art projects, with goals in mind to educate (6th grade), commemorate (7th grade), and celebrate (8th grade) Juneteenth.

Bulkeley students will come together on June 18 to display art and a 4”x 8” Juneteenth flag — clad with imagery and symbols from the life of several formerly enslaved people in Rhinebeck —at Town Hall. Seventh-grader Amaia Hayes is painting a night scene of her town, with trails and houses depicting the Underground Railroad’s path. She first learned about Juneteenth’s specific history in her classroom. “I think it’s really important that we have it off, to think about our history,” she said. Slavery wasn’t just a part of other towns’ histories, “it was Rhinebeck too, it was part of our community.”

Following the public installation, student art will be displayed year-round at 16 partnering businesses.

From racial reckoning to ‘correcting harm’

While these teacher-driven efforts to honor Juneteenth suggest a budding and real commitment to imparting a history that includes Black Americans, others urge for sustained, structural change in schools and communities.

“One of the key questions about Juneteenth is if it’s just performative — just a moment, and not a serious district-wide effort to advance racial equity — then to me it’s grossly inadequate to the moment,” King said.

Educators and advocates say the historical implications of Juneteenth warrant us to imagine beyond surface-level recognition. Krystal Hardy Allen, a former Louisiana elementary school teacher, doctoral student, and CEO of K. Allen Consulting, coaches educators and administrators in reframing their practices to be more inclusive. She notes that teachers may not have preparation time, historical context, or pedagogical frameworks readily available to teach about Juneteenth or the legacy of slavery. While districts grapple with how to teach about Juneteenth and move to recognize it as a holiday, she said, they also need to be mindful of treating their Black staff in equitable, inclusive, and respectful ways.

“It is a near slap in the face to give people a day off to commemorate a holiday — calling it Jubilee Day, Freedom Day, Juneteenth, etc. — but behind closed doors, foster an environment that is not psychologically, emotionally, and physically safe for them,” Allen said.

Outside of the classroom, Juneteenth has been an opportunity for community education, celebration, and broader political action. Organizers in Newark, New Jersey, Evanston, Illinois, and St. Paul, Minnesota are utilizingJuneteenth events to push for reparations and policy change to counteract centuries of systemic racism — and for the legacy of slavery, at the very least, to be examined more thoroughly.

The New Jersey Institute for Social Justice has co-hosted Juneteenth events for years. Organizers say 2021’s will be its first explicitly advocating for reparations, specifically, passage of a bill to create a state reparations task force “to look at New Jersey’s very particular history when it comes to these things, and come up with sweeping policy recommendations that address our particular brand of structural racism,” said Laurie Beacham, the Institute’s director of communications.

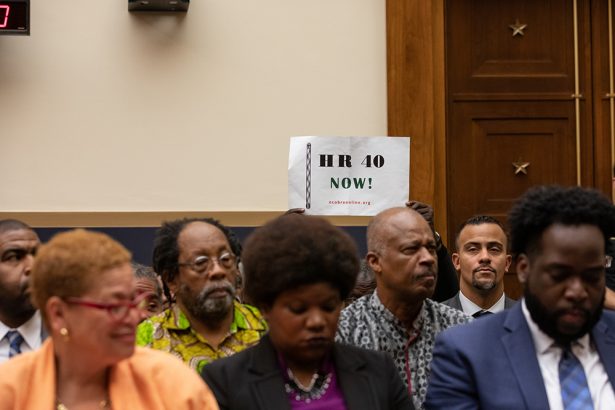

Newark residents and reparations supporters say there’s never been a better moment to act, given widespread dialogue on racial inequality. In 1989, federal legislation for a commission to study the history of slavery and reparations died in committee. Now three decades later, it’s been reintroduced in the House with more than 180 Democratic co-sponsors.

Congressional Black Caucus members are pushing to bring the bill to a vote this month, in the wake of the 100-year anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Even if moderates join the tide and it passes the House, there is slim chance of it winning approval in the Senate, where Republicans are concerned that a reparations commission could lead to unprecedented cash restitution.

This national momentum to examine the negative impact of government and institutional policies on Black families is also taking place at the same time that GOP-led states pass laws to restrict teachers from having the very conversations that link Jim Crow laws to systemic racism and the concept of reparations.

“It’s nice to have a day off, but it’s better to have a policy that reflects the importance of why we have the day off,” Natasha Capers, a New York City public school parent and director of NYC’s Coalition for Educational Justice, said. CEJ advocates for culturally responsive education, the policy aim of their annual Juneteenth event. “When we talk about reparations it’s about correcting harm. It’s not about individual wealth, it’s how do we pour this back into schools, how do we pour this back into infrastructure, how do we pour this back into land ownership?”

For supporters, correcting harm is at the heart of calls for reparations. Capers notes that Black, Indigenous, and Asian families did not see generational wealth because, for centuries, white families profited from their exploitation. Holding this fact in tandem with what happened on Juneteenth helps explain why the date finds itself perpetually a cause for celebration and political action — it marked the end of one form of exploitation (slavery), yet the start of another (Jim Crow).

Young people across the country are working to understand what comes after reckoning, celebrating Junteenth and positioning it in a larger political moment through spoken word or calls to action. Samiyah Webster, a high school junior in Newark, seeks out opportunities on her own to learn, participate and share outside of the classroom, noting the opportunity to do so in-school is inconsistent. “I think it’s important to be aware of the history aside from the stuff that they teach you in school”, she said.

She’ll be attending the Institute for Social Justice’s Juneteenth rally for reparations, and hopes that people become more aware of what reparations mean and that Newark practices them. “It is basically making amends for things that someone did wrong.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter