As COVID Closed Arizona’s Classrooms, Black Mothers Launched Their Own Microschools With Focus on Personalized Learning, Ending School to Prison Pipeline

By Marianna McMurdock | January 26, 2022

In the Arizona desert, a new school model has Black parents driving across city lines to drop their children off each morning.

Frustrated with what they say is their public schools’ failure to provide quality education and nurturing environments for Black children and fearing the persistent school to prison pipeline, a group of mothers, many public school teachers, have created a network of their own schools.

Launched mid-pandemic just one year ago, the mothers’ goal is to grow the seven micoschools into 50.

“We could be advocating 24/7, and still not make the impact that we wanted to see. So, what do you do, do you go charter? Do you try to keep working in the public school system? Nope, nope, not us. We said, well, we can do it ourselves,” said Debora Colbert, executive director of the Black Mothers Forum, a Phoenix-based parent advocacy group.

In mixed-grade classes, students learn at their own pace and are guided by two teachers. Restorative discipline techniques, not punitive strategies, are the norm.

The Forum’s approach to learning has caught the attention of Arizona Governor Doug Ducey in a state where high school graduation rates hover about 8 percent below national averages and less than half of the graduating class went on to college in 2020.

With little to keep them there, students who do go onto higher education often leave the state and don’t look back, Colbert said.

In Phoenix-area churches, nonprofits and shared school buildings, 42 students comprise the first microschools launched last January with preliminary guidance from national microschool giant Prenda. The Forum’s sites have since made the transition to public charter schools within local network EdKey Sequoia Choice. (Arizona’s attorney general reportedly opened an investigation last year into Prenda’s operations with a separate, online EdKey school. Prenda lawyers say the investigation has since closed. The Attorney General’s office did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Many of the Forum’s teachers, dubbed “learning guides” per the Prenda model, are religious leaders and parents from the community — many of whom left their placements in traditional schools for the opportunity.

Founders of the schools hope to change perceptions of the community they’ve so often heard from young people: “There’s nothing to keep me in Arizona, or Phoenix, to realize my dreams and my goals,” said Colbert.

“That’s not okay. We’re on a mission to kind of track where our children are, where they’re going, whether they are successful, and how to keep them connected to their communities,” she said.

Gov. Ducey has committed nearly $4 million in the last year to help grow its network of microschools to 50.

The forum has advocated for school reform since 2016, after nationwide violence against Black children and a series of high-profile police brutality cases involving Black Americans. Their mission became eliminating low expectations for Black children and school discipline policies that often end with Black children funneled into prison.

While the learning pod movement swept across the country’s white, affluent areas during the pandemic, outrage grew as the pandemic afflicted Black communities more than any other group and academic gaps grew along racial lines.

The moment became an opportunity for the Black Mothers Forum to formally launch and recruit for their own schools in January 2021.

Forum teacher and mother Tiffany Dudley believes having teachers who “looked like” her children at the microschools have made all the difference for her sons, Xavier, 7, and Jeremiah, 10.

“I kind of underestimated how much of a difference my child, being in an environment where he had people with the same skin color… how much of an impact mentally that had on him,” said Dudley.

Dudley often got calls from Xavier’s previous schools’ teachers about the “little things,” like how he played with his shoe laces instead of participating in a group activity. Mornings used to bring protests because he hated going to school.

After four months of microschooling, Xavier calls his out-of-state grandparents to recap school projects.

“Just literally being there in that environment changed how he perceived learning, and changed how he saw himself,” Dudley said.

Now a learning guide for a third through eighth grade cohort, Dudley said the student to teacher ratio, 10:2, is critical to help students transition from traditional schools.

There’s no hiding behind a dozen other peers who may be more vocal in the classroom, for example. Instead students are asked to problem solve, with support from teachers like Dudley:

“‘Okay, did you try this? How about we ask a friend?’ We’re just giving them strategies to teach them how to think critically to be able to solve problems because they are very used to being spoon fed answers,” she said.

The smaller classes allow their “connect, redirect” model, a complete departure from the no-excuses disciplinary policies many other charters adopted, to be the norm. When a student disrupts class or has trouble with an assignment, one guide talks with the child to uncover what might be affecting them. They then connect them to time, space, a venting session, food, counseling.

“They’re not going to be punished — this is an opportunity to figure out what’s going on … giving them that sense of ownership in that redirection, they are part of this process, that takes time,” Black Mother’s Forum Founder Janelle Wood said. “That’s why we need two learning guides in the space. If one child is having a problem, all of them may not be having the same problem. They can continue on with what they’re doing, but this one child may need some extra attention.”

In crafting schools with Black families at its center, the Forum also reimagined their physical locations. Instead of operating out of a family living room or garage, schools and community organizations were more realistic because their families didn’t have the extra space to host classes.

Renting church and nonprofit space provides added benefits, too: kids stay connected to Phoenix, and community groups that lost revenue during the pandemic are supported financially.

And since last school year, they’ve added an hour of instruction to each school day. The extra time preserved their morning wellness circles — students start each day by talking through their emotions — and independent reading, with which many struggle.

In perhaps the starkest intentional departure from traditional schools, students learn via the mastery approach in blended classrooms of students of different ages and grades, separated into K-2 and 3-8.

Through online learning tools like Zearn and iReady, some work grade levels ahead, others spend necessary time with foundational concepts like multiplication, as guides check in one-on-one.

Wood recognized their efforts had “to start at the school level, because that’s where our children, Black and brown children, are being negatively impacted at the highest level.”

Raina Chamblee, now a third grader at one of the microschools, recalled how her former Wisconsin public school was a particularly negative experience.

Diagnosed with ADHD, a new medication she was trying made her drowsy. She’d fall asleep in class, taunted and teased by classmates — behavior left unchecked by the teachers.

Once, a teacher lashed out at her directly.

“I colored a pink polar bear and then one of my teachers crumbled it up and threw it in the garbage,” Raina said.

Dudley said some of the difficulties Black children experience in school stems from the assumption that “‘this is a behavior problem’ […] instead of looking deeper to see, really see, the child.”

It’s why, she said, the miscoschools’ personal approach and connect-redirect models are necessary.

Detailing the last few months in Phoenix, Raina said her new school has made a difference in her learning. New teachers “push” and “help,” she said.

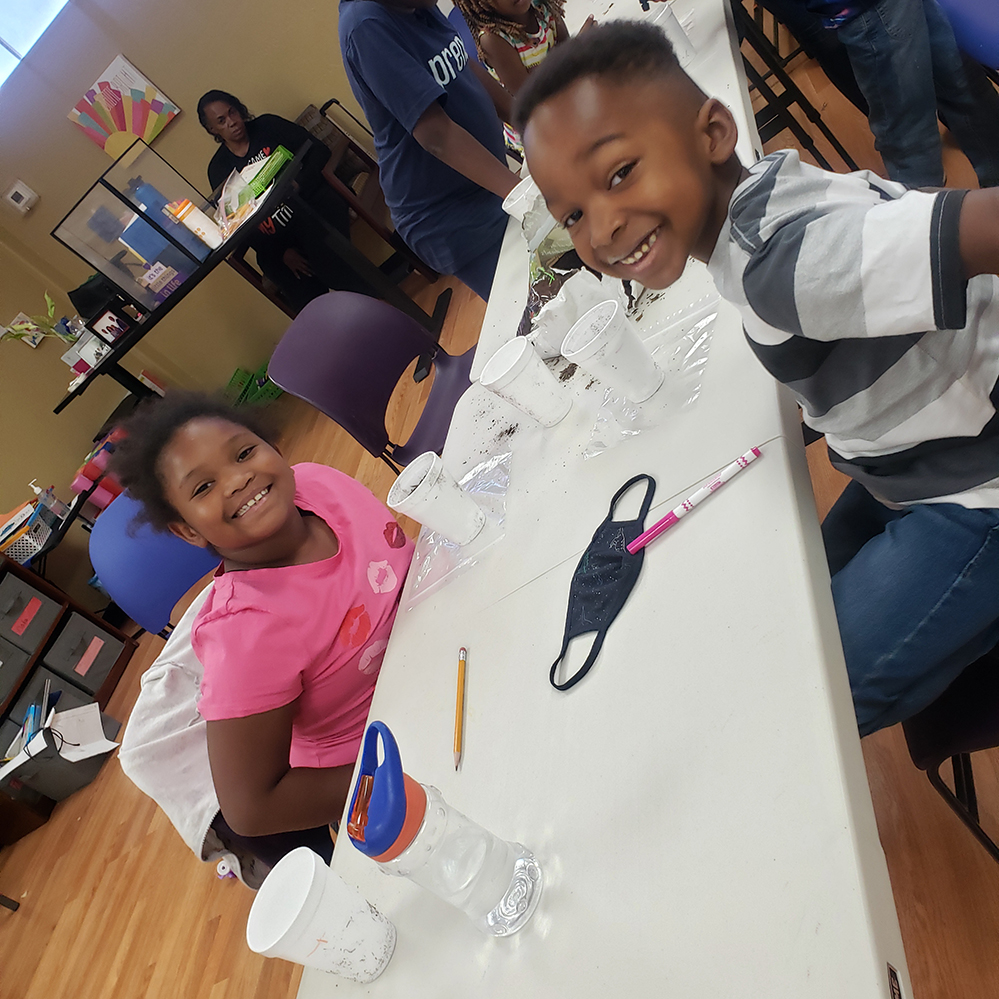

Raina, 10, Triston, 6 (Kylie Chamblee)

Her mother, Kylie Chamblee, noticed a difference in her ability to teach, too. She’s making deeper connections with her students.

When a student needs extra time with reading comprehension and is ahead in geometry, she can work with them more freely.

“That’s what I really like about our model for kids,” said Chamblee. “Because it can be challenging but then it can also be rewarding, because they’re getting what they need.”

Lead Image: Black Mothers Forums

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter