When Parents Disagree Over Doses for Kids: How Mothers’ Caretaking Instinct May Be Slowing Youth COVID Vaccination

Updated, June 23

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Fatou and Modou have two healthy children. A 5-year-old boy who likes to build Lego towers. A 7-year-old girl who’s into anime. With each parenting decision the couple has faced over the years — picking a religious Sunday school for their kids, setting bedtime — they have mostly been on the same page.

But now, the Pawtucket, Rhode Island family is split over one of the most fundamental questions of the pandemic: whether or not to vaccinate their kids against the coronavirus.

Modou, the children’s father, who asked to be identified by his middle name because of the sensitivity of discussing a family health issue, is undecided on whether he would choose to get the kids vaccinated once they become eligible — he’d need to research it more first, he says — but he’s largely open to COVID-19 immunization. The 36-year-old works as a nursing assistant at a state hospital and rolled up his sleeve in December of last year, as soon as the shot became available to him as a health care worker.

“It’s necessary for everyone to get the vaccine so the country can keep moving,” he told The 74.

But Fatou, who also asked to be referred to by her middle name, strongly opposes vaccinating the children.

She knows the shot offers protections and she knows young people can become seriously ill from the virus — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hundreds of minors have died from COVID-19 — but the risks are greatly reduced for kids compared to adults, she points out, and the 32-year-old mother worries that the shot may have unforeseen side effects.

“Your kid could … be the kid that has the negative reaction to the vaccine,” she told The 74.

“I can’t call myself an anti-vaxxer,” Fatou maintains, because both of her kids have received all the immunizations necessary for school. But she herself has also chosen to skip the COVID-19 shot. She understands the public health imperative, but something about the vaccine doesn’t sit right with her.

“It’s a gut thing,” said Fatou. “I don’t want to be the guinea pig.”

The Pawtucket mother possesses a disarming self-awareness about her stance. She doesn’t speak much about the vaccine in public because she knows it’s important for as many people to get vaccinated as possible.

“For the general health of everybody, it’s better for people like me to keep our opinions to ourselves,” said Fatou.

But even if Fatou and other like-minded moms are not outspoken on the topic, it appears that the Rhode Island family’s predicament may well encapsulate a growing split among parents over the vaccine.

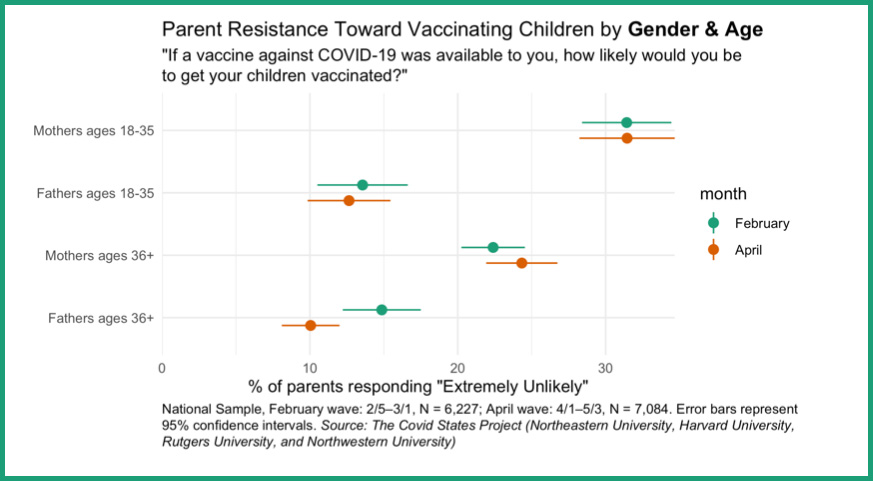

While women have received coronavirus shots at higher rates nationally than men throughout the pandemic, polling indicates that higher shares of mothers than fathers are resistant to vaccinating their kids — especially among parents under 36.

A May study, based on a survey of over 21,000 people across all 50 states published in collaboration between universities such as Northeastern, Harvard and Rutgers, found a widening gap between mothers’ and fathers’ stances on inoculating their children. Since February, the percentage of fathers who said they were “extremely unlikely” to vaccinate their kids fell from 14 percent to 11 percent, while the share of mothers who said the same held constant at 27 percent. Among moms under 36 years old, nearly a third said they were resistant to vaccinating their kids.

“The big gap persists,” Matthew Simonson, lead author of the study, told The 74. “Fathers are becoming less resistant and mothers aren’t.”

As the U.S. struggles to sustain its pace of vaccination and with President Joe Biden acknowledging Tuesday the administration would not meet its goal of giving at least one shot to 70 percent of adults by July 4 now, the parent polling numbers present a problem for America’s vaccination campaign, says Simonson, a Ph.D. candidate at Northeastern University. In cases where moms are against immunizing their kids, youth vaccinations rarely happen, he said.

“Mothers are the primary decision makers about whether the children get vaccinated or not,” says Simonson. “Even if the fathers may be more willing, the mothers are the ones who are more involved in scheduling appointments and making health care decisions about their children.”

Such is the case for Fatou and Modou. Though the parents’ stances on the issue diverge, Fatou says that the ball is “more in [her] court” for any final decisions.

She is not ignorant to the stakes of the pandemic. In October of last year, COVID-19 claimed the life of her dearest friend’s father, who she described as one of her “parent role models.” He had coached her basketball team growing up, and Fatou and Modou, who are Muslim, would attend Christmas parties at his house every year.

The pandemic “definitely has hit closer to home,” Fatou said.

Still, the personal experience has not made Fatou any less skeptical about the vaccine. She tried reading academic journals on the topic, but had a tough time decoding the findings.

“[Studies] can tell me that five plus seven is two, and I will be like, ‘Oh, OK, that makes sense in your world,’” she said. “It’s all a trust game for me because I just don’t feel like I can understand all of the pieces at play.”

So Fatou, who works as an advisor for Upward Bound at Rhode Island College, is left trying to make sense of what she hears from others. That’s true of many mothers, says Simonson.

“The way that we make these decisions is not in isolation, it’s socially,” said the Northeastern researcher.

He says the social factor may represent a major part of the vaccine hesitancy equation, especially for moms. Simonson hypothesizes that among young mothers who socialize with other young mothers, there could be an “echo chamber effect” that stigmatizes COVID-19 shots for children.

In a portion of his study where respondents typed into a text box to explain their personal reasons for not getting vaccinated, many individuals expressed concerns over the authorization process, worrying that it was still an experimental vaccine, Simonson explained. Extrapolating to children, it would be reasonable to conclude that the caretaking instinct is a key component of some mothers’ resistance, he thinks.

“It’s coming from a place of really wanting what’s best for their children and thinking, mistakenly, that they’re playing it safe by being vaccine hesitant. Whereas actually, playing safe is to get your kid vaccinated,” said Simonson.

In fact, over 300 young people have experienced heart inflammation after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, a higher-than-expected number which may be stoking parental fears. A CDC safety group said Wednesday there’s a likely association between the condition and the vaccine, mostly in adolescent and young adult males after receiving their second shot. The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices was meeting Wednesday to assess the situation. CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky has stressed that heart inflammation cases in young people are still exceedingly rare and are, in most instances, mild. The benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks, she has said. Others, however, are not so sure, including Dr. Marty Makary, a professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health, who is recommending kids not get the second dose of the vaccine until the heart complication is “properly reviewed.”

As the more infectious Delta COVID-19 variant takes hold in the U.S., health experts have voiced concern that unvaccinated young people could become a focal point for viral spread this summer and fall. Philip Chan, medical director for the Rhode Island Department of Health, knows that kids can fall seriously ill when they contract the virus and encourages parents of vaccine-eligible children to get their kids immunized.

“The vaccines are highly effective against the Delta variant,” he told The 74. “We have to vaccinate everyone in order to get through this.”

Highlighting a silver lining from his study, Simonson points out that parents of older children report being marginally less vaccine resistant than parents of younger kids. That happens to align well with the chronology of the FDA’s expansion of emergency use authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. The Northeastern University researcher hopes that, over time, there will be a “trickle down” effect, by which younger parents become more open to immunizing their own kids after watching as slightly older children safely receive COVID-19 doses.

Modou, who knows his wife needs to make an independent decision on the issue, hopes that a similar evolution may occur in his household.

“I’m not really that forceful,” he said. “I tend to just lay back … and maybe she would come around.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter