Partisanship Alone Didn’t Determine School Reopenings, New Study Argues

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

What made so many K-12 schools stick with remote learning to begin the 2020-21 school year, even as others reopened their doors to in-person or hybrid instruction?

According to a slew of research that emerged last year, much of the answer boils down to simple politics. Multiple studies from political scientists at Michigan State University, Boston College, and the Brookings Institution suggested that school reopening decisions were significantly more correlated with local political affiliation — as measured by the results of the 2016 election, or sometimes by strength of teachers’ unions — than the prevalence of COVID-19. Like so many other events in American life, our responses to the pandemic were heavily governed by how we vote.

But a new analysis complicates that picture somewhat. The paper, released on Monday by Tulane University’s National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice, confirms that politics helped determine how local authorities responded to the coronavirus threat in schools. But reopening approaches were also closely correlated with community demographics, and health conditions played a role as well. What’s more, given the interdependent relationships between all of those variables, it’s extremely challenging to isolate just one as being the most influential on policy makers’ decisions last fall.

Douglas Harris, an economics professor at Tulane and one of the report’s co-authors, said in an interview that the mix of potential causes yielded “probably the least amount of certainty about what the actual conclusions are of any study I’ve ever done.”

“In this case, that’s part of the point,” Harris said. “What we thought was certain is actually a little more uncertain, and given the political polarization we’re in right now, we don’t want to overstate the role of politics here.”

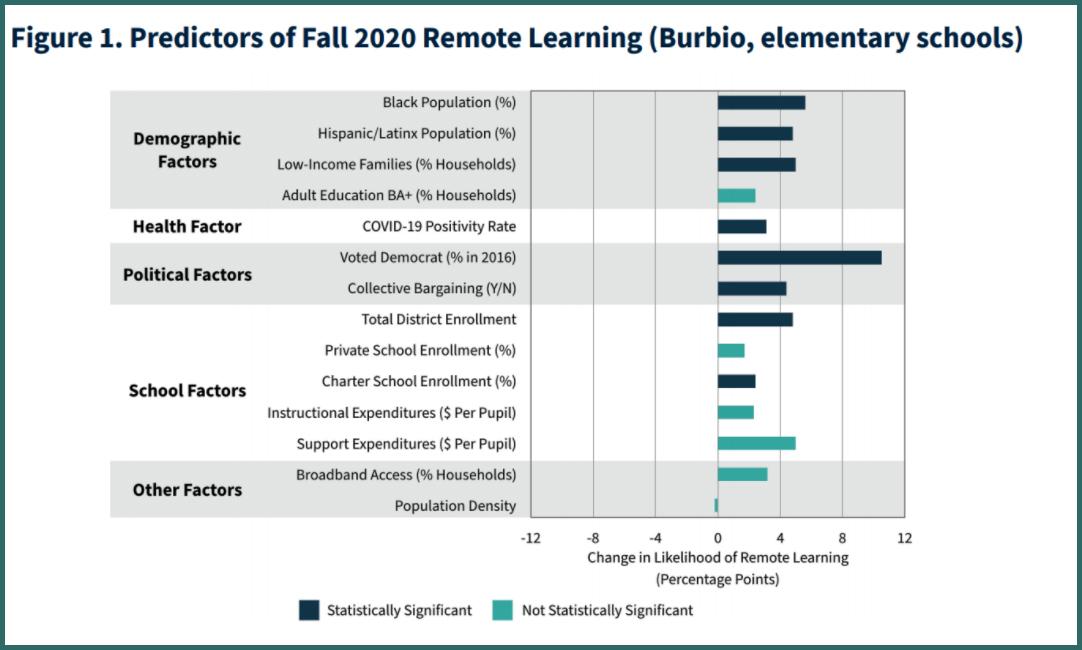

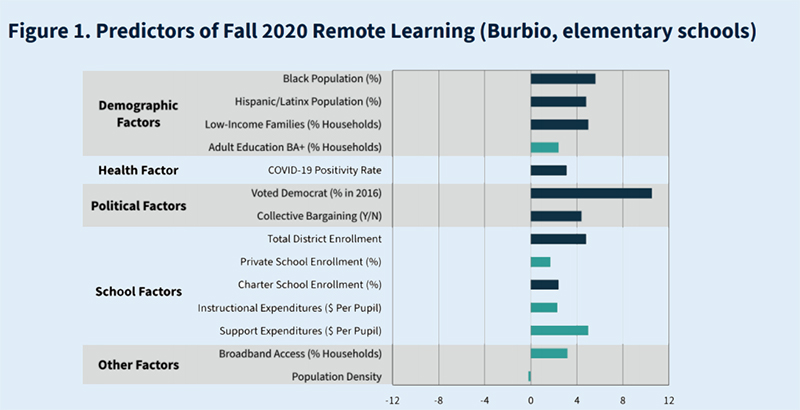

Using data on over 1,100 school district reopening decisions from Burbio.com, Harris and Tulane research fellow Daniel Oliver examined which stayed remote or switched to in-person learning both last fall and in the spring of 2021. Without weighting by state or district size — a small district’s decision counted as much as a large one’s — they then examined the respective racial and socioeconomic demographics of each area, their COVID positivity rates, the county-level vote share won by Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, as well as factors like local charter school enrollment and broadband access.

As in previous studies, they found that partisanship was an important determinant of whether schools opted for virtual learning to begin the 2020-21 school year. An increase in Clinton’s 2016 vote by 14 percent was associated with a 10.5 percentage point increase in the chance that local schools stayed remote. Whether teachers were allowed to collectively bargain was also linked to COVID decisions.

But a variety of demographic factors clearly play a role as well. Black, Hispanic, and low-income people living in a district were all associated with higher likelihoods that virtual learning continued last fall. Those trends dovetail with public opinion research released over the last year, which has consistently showed that non-white parents are more concerned about the return to physical classrooms than their white counterparts.

Harris said that while 2016 voting patterns were the single strongest indicator of how districts acted, the totality of demographic evidence was equally compelling.

“You’ve really got one measure of political dynamics — two, if you include union strength — whereas demographics represents a set of factors,” said Harris. “Individually, they all look not as significant as that Democratic vote share, [but] collectively, they may be just as important.”

The effects of most district traits were substantially similar in both fall 2020 and spring 2021. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 2016 partisanship was somewhat less significant following the ultra-contentious 2020 election, even while it remained the most predictive single factor. The predictiveness of COVID positivity rates was also reduced, to the extent that it was no longer statistically significant.

To make matters more complex, Harris added, demographics and politics can’t be isolated from one another. Black and Hispanic voters, along with voters living in poverty, are more likely to vote Democratic; according to public health data they were also much more likely to find themselves at risk from the effects of COVID. All of it, Harris argued, made it necessary to avoid elevating one condition, such as politics, above others.

“Part of what we were trying to highlight was how connected those things were, and how it makes it pretty difficult when voting patterns are closely connected to demographics — race and income patterns — and those things, in turn, are closely correlated with COVID health risk. Whenever you have a bunch of interconnected factors like that, which are probably all playing some role, it becomes difficult to isolate one.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter