High Schoolers Who Took Remote Classes During Pandemic Experienced a “Thriving Gap,” According to Duckworth-Led Study

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

The academic damage inflicted by the pandemic is still being measured, but early indicators are ominous. Exam scores collected periodically by states, cities, and nationwide testing organizations show that a large number of K-12 students have either stagnated or lost ground in their studies during the COVID era. School closures and prolonged doses of virtual instruction are usually identified as the culprit.

But since classes first went online last spring, parents and educators have been equally anxious about the pandemic’s impact on children’s inner lives. And while those worries have often focused on the developmental opportunities denied to kindergarteners and elementary schoolers, older students have also suffered while isolated from friends and teachers.

Research published today by the American Educational Research Association provides concrete evidence of the setbacks experienced by adolescents in remote learning. In a two-part survey conducted both before the emergence of COVID-19 and during its peak, high schoolers learning online said they were worse-off socially, emotionally, and academically than their peers learning in physical classrooms. The “thriving gap” between the two groups was more pronounced among older participants, the authors note.

The study was conducted by a group of authors at Temple University, Mathematica Policy Research, and the University of Pennsylvania, including prominent psychologist Angela Duckworth, a MacArthur Fellow best known for her writings on non-cognitive traits like grit. In an interview, Duckworth said that the post-COVID distancing “seems to have a deleterious effect in every aspect of thriving, in every way we were measuring it.”

“What we wanted to underscore was that there’s a consistent signal across these three domains,” she said. “We are finding this across social, emotional, and academic learning.”

The survey was administered through Character Lab, a nonprofit research consortium Duckworth co-founded in 2013. The group’s Student Thriving Index measures self-reported ratings of student well-being and school routines, which students complete at the direction of teachers during class time. A sample of roughly 6,500 students across Florida’s Orange County School District participated in the survey both in February 2020, just before the pandemic shuttered campuses, and October 2020, after they had been given the choice of whether to return to in-person instruction. About two-thirds of participants chose to stick with virtual classes.

Students were enrolled in grades eight through 11 in the spring, but all were attending high school during the questionnaire’s second round. In both iterations, they were asked to assess themselves by multiple test items related to social relationships (example: “In your school, do you feel like you fit in?”), emotional state (“How happy have you been feeling these days?”) and academic engagement (“Compared with other things you do, how interesting are your classes?”).

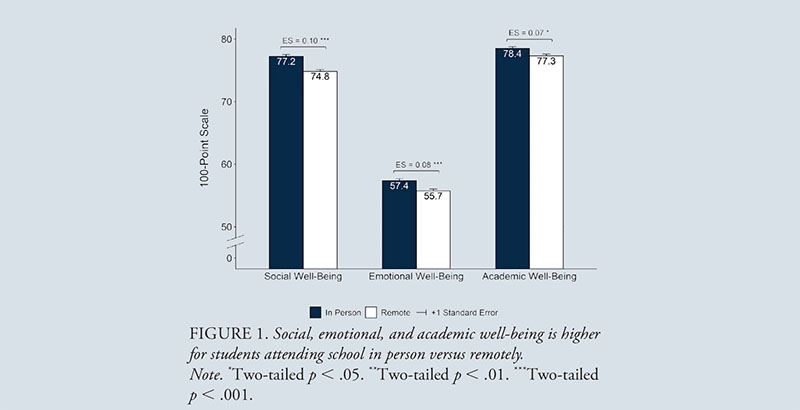

After grouping test items into composite scores, the research team found that students learning remotely reported lower scores across all three categories when compared with their peers who had returned to school. On a 100-point scale, remote students scored 2.4 points lower socially, 1.7 points lower emotionally, and 1.1 points lower academically.

The “thriving gap” detected in survey responses was driven overwhelmingly by students in grades 10-12, while differences in response for ninth-graders did not reach statistical significance. The authors offer a few possible explanations for the disparity, which may result from the fact that freshmen are already dealing with a crucial transition to the high school environment and may not be as disturbed by separation from peers or adults that they haven’t yet had the chance to meet in person.

Duckworth and her colleagues note that the effects, while substantial, should be viewed with caution. Given that students weren’t randomly assigned to participate either in-person or virtual instruction, the responses collected may not point to causation. The team controlled for a range of variables in the student population, including age, gender, race and ethnicity, eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch (a common proxy for poverty), English learner status, and GPA. The population of students who returned to school buildings were disproportionately male, white, ineligible for free lunch, higher in social well-being, and lower in GPA.

After spending large chunks of two academic years learning from home, many students are preparing to return to in-person instruction on a full-time basis this fall. As part of the push, President Biden has warned of the “devastating” impact of social isolation on students’ mental health. Even so, some families are arguing in favor of retaining a virtual learning option for their kids in the future.

Duckworth said that while most parents are justifiably concerned about the recent disruptions to the academic and social-emotional growth of young children, high schoolers should not be neglected when tallying the pandemic’s toll.

“Adolescence is the most social period of your life — you are programmed to want to be with people outside your family, and usually you find ways to do that. For a lot of students, school is a haven where they feel the most themselves. We wanted to quantify what it’s been like for this age group, and this trend we saw…was consistent with the idea that the more you are in adolescence, the more difficult it is for you to be holed up with your family and not seeing other people.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter