Stuck at Home, Separated from Teachers, Children May Have Faced More Severe Abuse During Pandemic, Research Suggests

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

The most obvious early effects of COVID-19 were the ways in which it shrank the spheres of life, work, and school. Within a few months of its emergence last winter, hundreds of millions of Americans found themselves stuck together in crowded homes, adults often sharing couch space with children stranded from their classrooms.

It was an atmosphere, many worried, that could drastically increase the dangers of domestic violence. As parents were left to ride out the economic instability brought on by sudden business closures, most K-12 students were no longer in direct contact with teachers, who are among the most common reporters of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse to children. Worries only grew as complaints of abuse plunged during the pandemic’s early weeks, with advocates warning that serious mistreatment was likely going unnoticed.

More than a year later, researchers are sounding the same alarm. Studies of both local child welfare agencies and national emergency room visits suggest that while total child abuse reports declined significantly last year, the cases that arose were more likely to result in medical exams and hospitalizations. And with more kids set to return to in-person classes in September, the findings raise the question of whether school systems will be prepared to assist large numbers of children who have suffered invisible trauma over the preceding 18 months.

Jodi Quas, a professor of psychological and nursing science at the University of California, Irvine, is currently studying patterns of abuse in a large, unnamed Southern California county. In an interview with The 74, she said that it “makes sense, when you think about family stress and economic insecurity,” that child abuse and neglect would grow more severe during times of intense upheaval.

“We have just one county, but it does look like kids are more at risk,” she said. “It’s the stress and uncertainty. It’s parents either losing their jobs or trying to work at home while engaged with kids in online school. All of those stressors, we’re guessing, contributed to increased anxiety with fewer resources and support systems available.”

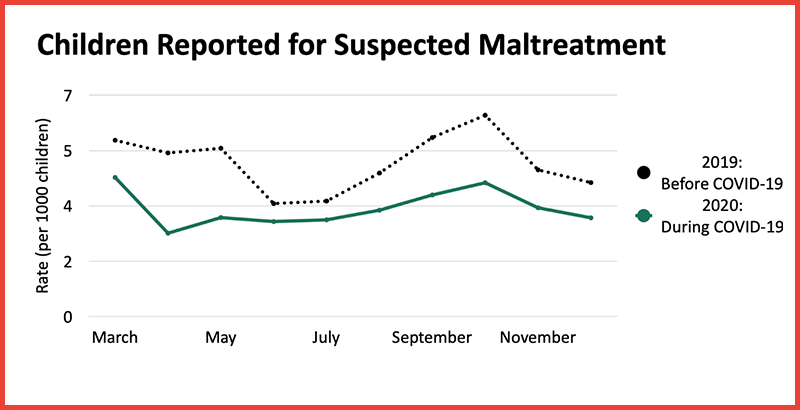

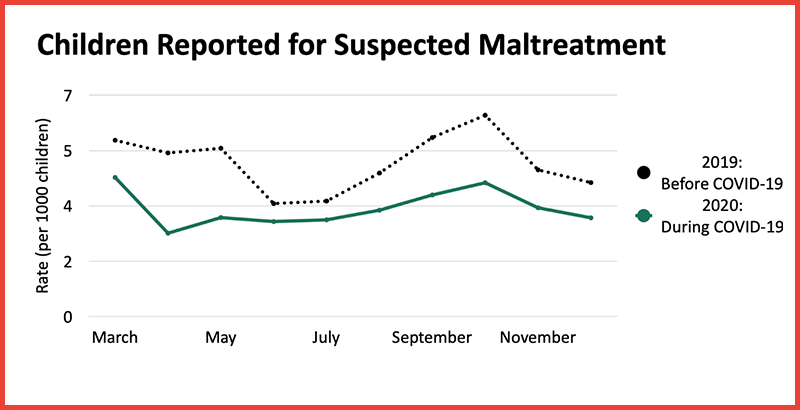

With co-authors Stacy Metcalf, a doctoral candidate, and Corey Rood, a pediatrician, Quas leveraged two sets of data — monthly reports of suspected child maltreatment from the county’s social services agency, as well as records of medical evaluations at a local child abuse clinic — to compare the trends between March and December 2020 with those of the same period in 2019. While their research is still under review and must therefore be read cautiously, the figures indicate that the number of abuse reports fell during the spring (-33.2 percent), summer (-13.1 percent) and fall (-24.5 percent).

The decline appears to be related to school closures: While one-third of abuse reports in the county came from school and daycare staff in 2019, the data show that just one-sixth did in 2020.

In most states, school employees like teachers and nurses are mandated reporters of abuse. A 2020 analysis from researchers at Cornell University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas found that time spent in school increases the likelihood that abuse will be noticed and documented. Educators’ prominent role is illustrated by the fact that reports typically decrease during the summer. Given the swift separation of students from schools during the past year, Quas said, it was predictable that reports were “absolutely going to drop, and you saw that in the first months of the pandemic.

Though complaints to social services fell, Quas and her team found that the number of children who received medical evaluations at a local child abuse clinic increased by 30 percent. They also measured an increase of seven percentage points in the proportion of children who received examinations once they were referred to the clinic — in essence, a sign that the cases of serious, hard-to-ignore abuse grew as a percentage of total reports.

‘What happens in the fall?’

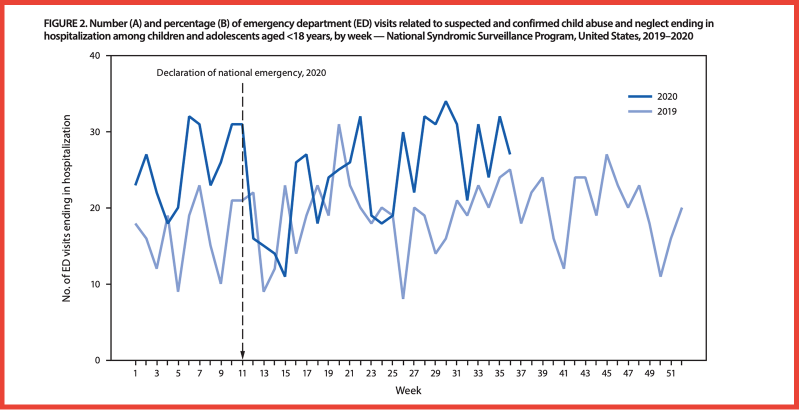

That finding corresponds with evidence from an analysis of hospital records released in December by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That research found that, in the four weeks immediately following President Trump’s COVID-19 emergency declaration last March, emergency room visits related to child abuse and neglect fell by more than half compared with the same period in 2019. The decline was apparent across all children and adolescents, with visits for kids between ages 5 and 11 dropping by 61 percent.

But the most concerning of those visits, those resulting in hospitalization, stayed steady throughout September 2020. In total, the percentage of all maltreatment-related ER trips that led to hospitalizations of children jumped significantly, from 2.1 percent in 2019 to 3.2 percent in 2020. That average includes increases from 3.5 percent to 5.3 percent for the youngest children, and a near-doubling (from 0.7 percent to 1.3 percent) for children between 5 and 11.

Dr. Elizabeth Swedo, a CDC researcher and one of the brief’s authors, warned in an email that because of the massive disruptions to the medical system that occurred last year, the hospital data needed to be interpreted with care. Even in normal circumstances, hospital trips can vary substantially by season, and in 2020, the swings were much larger than normal.

“Visits for almost all non-respiratory diseases and conditions dropped precipitously in March 2020,” Swedo wrote, “in large measure due to patients being more reluctant to travel or seek medical care during the pandemic.”

“These denominator shifts presented challenges for interpreting data and communicating complex findings,” she added.

Swedo said that local research of the kind that Quas and her collaborators are conducting “really help contextualize the findings from our national study,” adding that it would be critical to incorporate future data released by national resources like the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Center and the National Violent Death Reporting System.

It’s still unclear how the factors that may have contributed to worsening abuse and neglect have responded to the gradual improvement in the economy and public health conditions. Prior studies have shown that quarantines, and particularly lengthy ones, can lead to fear, anger, and symptoms of PTSD. Studies looking specifically at the COVID era suggest that the workers most affected by the pandemic endured damage to their mental health, and living under a stay-at-home order was associated with loneliness and anxiety.

Even with COVID cases and deaths back on the upswing in recent weeks, more adults and kids are beginning to resume their pre-pandemic routines. But Quas noted that school districts might need to get ready to identify and provide services to a sizable group of students who spent the 2020-21 school year not just isolated from teachers and friends, but also under threat from adults in their homes.

“What I’m thinking about is, what happens in the fall? Not that the pandemic is fully over, but by fall, I think more kids are going to really be back in school after a pretty long period. How do you prep for what we think might be an increase in reporting that could happen then, as kids go back to school more consistently?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter