The Gifted Gap: Best and the Brightest among Black & Low-Income Students Fall Behind Their Whiter, More Affluent Peers, Study Finds

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Efforts to improve the quality of American education often focus, implicitly or explicitly, on students who are achieving at levels far below their peers. That emphasis is reflected in equity debates about kids who are tragically under-equipped to thrive as adults, as well as policy remedies that target “failing” schools for their low test scores and rates of high school graduation.

But research released today suggests that access to educational opportunity is also unequally distributed among children at the top of the academic heap, and that even some of the brightest young students are at a high risk of being overlooked within their schools and districts.

The study, commissioned by the reform-oriented Thomas B. Fordham Institute, points to clear disparities in the prospects of high-achieving students along lines of race and class. Black and low-income elementary schoolers in Ohio who scored well on state exams were less likely to be classified as gifted and talented than comparable white and high-income children. Into middle and high school, they achieved at lower levels on standardized tests, Advanced Placement exams, and college entrance exams, and they were less likely to enroll in college.

Scott Imberman, the report’s author and an economist at Michigan State University, said that it wasn’t certain whether the lower rates of gifted identification exacerbated the performance gaps between student populations. Beginning in 2017, Ohio mandated more comprehensive screening for gifted status in the early grades, but historically, even some students who received that status have gone without gifted services.

“The main thing here is that there was, and probably still is, a problem with these gaps,” Imberman said. “These higher-achieving minority and disadvantaged students were not performing as well, over time, as high-achieving students who were advantaged, and they were also less likely to be enrolled in gifted programs.”

To study the long-term trajectories of academically promising students, Imberman sought student-level records from the Ohio Longitudinal Data Archive, which included third-grade performance on Ohio’s state standardized test for over 900,000 participants between the 2005-06 and 2011-12 academic years. Imberman focused on students of all backgrounds who scored in the top 20 percent statewide — a sample of roughly 180,000 — and matched those results with scores on the ACT and SAT, as well as college enrollment figures from the National Student Clearinghouse.

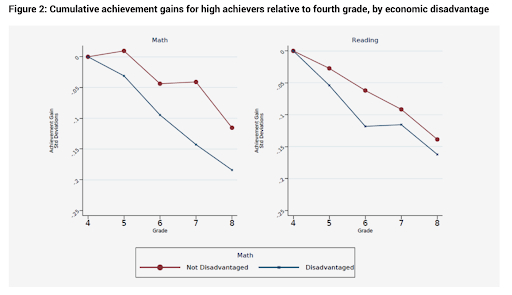

In terms of both short- and long-term academic performance, poor and African American students who scored in the top 20 percent fell behind their peers. Subsequent standardized test scores from grades 4-8 revealed that high-achieving students generally lost ground to their classmates in the bottom 80 percent, principally due to improvement among lower-performing students in late childhood and early adolescence. But in both reading and math, the relative performance of high-achievers who were white, Hispanic, Asian American, and higher-income held up significantly better than their economically disadvantaged and African American classmates.

High school assessments showed evidence of the same persistent differences. Black and disadvantaged students who were high-achievers in the third grade were less likely to take the ACT test and AP tests, and scored lower than other high-achievers when they did. The average AP scores for more affluent students (3.2 on a five-point scale) and white students (3.1) were notably higher than less affluent students (2.6) and African Americans (2.3).

Finally, 57 percent of white high-achievers later enrolled in a four-year college, compared with 53 percent of Asian Americans, 30 percent of Hispanics, and 26 percent of African Americans; among students who weren’t classified as economically disadvantaged, 58 percent later enrolled in a four-year college, compared with 35 percent of high-achievers who did receive that classification.

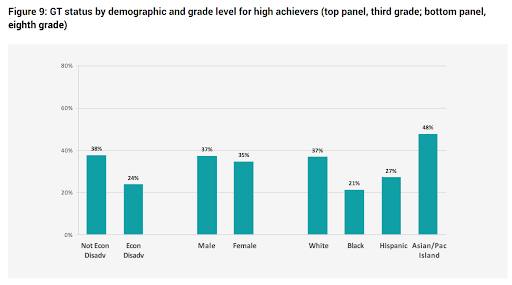

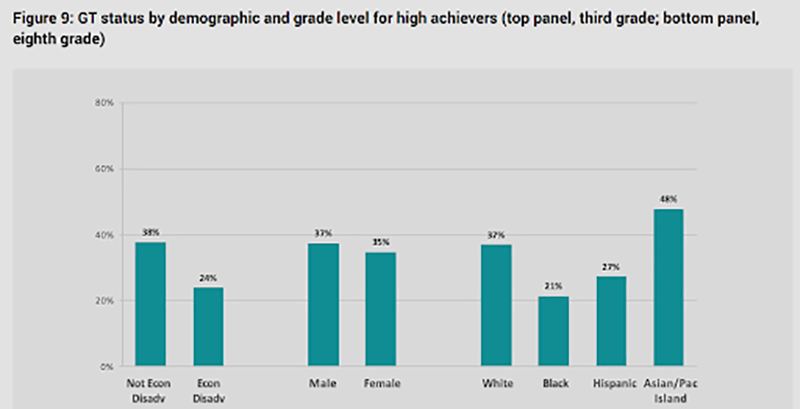

In a separate set of conclusions that may offer a partial explanation for those sharp divergences, Imberman found that students from different demographics were identified for gifted and talented services at vastly different rates. Black and low-income high-achievers are less likely to be identified in the third grade than other student groups, and the gaps substantially grow by the time they’ve reached the eighth grade.

In fact, the report finds that simply being identified as gifted may carry some achievement benefits: Receiving the gifted classification in math led to a modest increase in reading scores of .02 standard deviations and a boost to math scores of .03 standard deviations — equivalent to a performance boost of roughly one percentile annually. What’s more, those effects were relatively larger for African American and Hispanic students than white ones.

The findings echo those of a 2016 paper published by economists David Card and Laura Giuliano, which found that when a large urban school district adopted universal gifted screening for second graders, it led to large increases in the number of minority and low-income students who were classified. A 2018 study from Fordham found that just 61.5 percent of K-12 schools in Ohio offered gifted programming, and less than 8 percent of students enrolled at those schools received access to them.

Imberman called the effects on achievement “plausibly causal,” noting that social factors other than gifted identification might play some part in explaining the effects.

“I’d say that this provides some prima facie, suggestive evidence that expanding access to gifted education among minorities, in particular, could be a way to help reduce these gaps among high-achievers,” he told The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter