New Study Shows Reading Remediation in Middle School Led More Students to Attend College and Earn Degrees

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

College remediation has earned a bad reputation over the past few years. Hopeful students spend billions of dollars annually to review material they should have mastered in high school, and a huge number never complete the coursework they are assigned. The fact that many undergraduates pay to attend catch-up classes when they are actually capable of succeeding in college-level work has only heightened scrutiny of the practice.

But while we tend to associate remediation with older students, it’s not just a feature of university campuses — and new research suggests that adolescents who take remedial classes are better prepared for academic success in high school and college.

The study, accepted for publication at the Journal of Public Economics, finds that Florida middle schoolers who were assigned to complete a year of remedial instruction in English earned higher scores in state testing; those effects diminished over time, but the same students saw an impressive range of benefits as time went on, including higher rates of college enrollment and degree attainment.

“Overall, I think the findings here suggest that middle school remediation could be an effective lever in improving college readiness,” said Umut Özek, the paper’s author and a researcher at the American Institutes for Research.

The research examines the effects of a Florida law passed in 2004 as part of the state’s dramatic acceleration of accountability-focused education reform under then-Gov. Jeb Bush. Under the policy, middle school students scoring below proficiency levels in either math or English must complete two courses the next year — one grade-level class and one remedial class — in the same subject.

The law ultimately applied to a significant portion of students across the state, but Ozek chose to study one anonymous, urban school district serving a racially diverse population of over 200,000 students. Many fewer students were assigned to supplementary coursework in math than reading, so he focused on English, gathering test scores for K-12 students between the 2005-06 and 2018-19 school years. He also examined course enrollment data, including both advanced and remedial classes, and linked it with records from the National Student Clearinghouse that showed trends in college enrollment and completion.

To capture the specific consequences of the policy, Ozek compared the academic performance of two broadly similar groups of students — those who scored just under the cutoff for remediation assignment and those who scored just over it.

In all, he found that the effects of English remediation were strikingly positive in terms of immediate standardized test results. Students who experienced a year of the combined courseload saw their reading scores on subsequent state exams jump significantly, even as they were no more likely to be absent from school or be suspended following a disciplinary incident. As Ozek notes, the higher test scores faded over the two years following their experience with remediation.

But there’s a long-term upside: Even given the diminution of testing improvements, students who completed remedial coursework alongside their grade-level English class enjoyed a variety of advantages over their otherwise comparable peers. As high schoolers, they were 21 percent more likely to take part in college credit-bearing material, such as Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes (for advanced English classes, the figure was 38 percent).

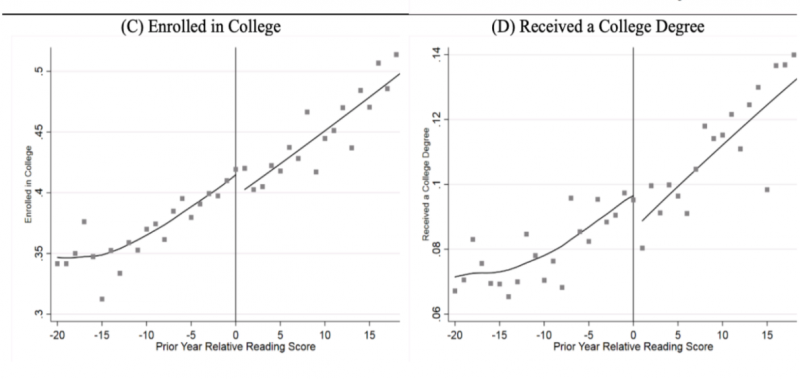

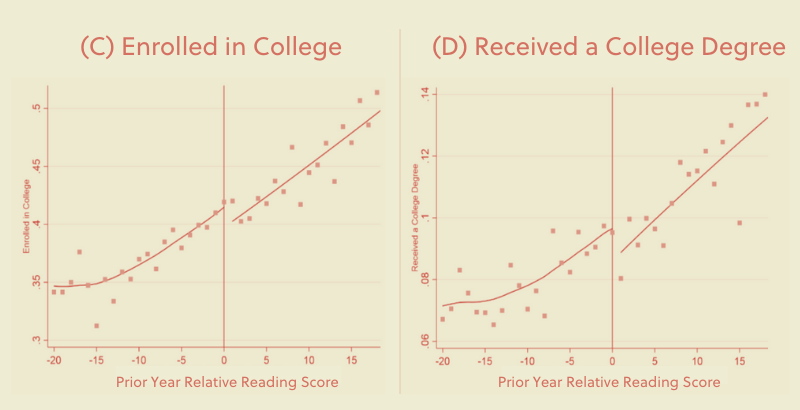

The benefits stretched into post-secondary education as well. Former remedial readers were 5 percent more likely to enroll in college, 15 percent more likely to persist past their first year, 50 percent more likely to attend a highly competitive college, and 43 percent more likely to eventually attain a two- or four-year degree.

The explanation for their gains can likely be attributed to the way in which remediation reshaped their middle school experience. Given the double dose of coursework, it’s unsurprising that Ozek found remedial students receiving almost an hour of additional English instruction each day. But he also found that their average class size in English was reduced by about 2 students, and they were significantly more likely to be assigned to a highly effective teacher (as measured by their impact on student test scores). As a downside, they were less likely to take part in music and physical education classes during their time in remediation, and their likelihood of being assigned to advanced classes in other subjects was sharply reduced.

Ozek observed that part of the reason the policy was feasible was that it applied to adolescents, who have few alternatives if they are alienated by the addition of a catch-up class; ample research shows that students in high school or college sometimes handle the frustration by simply giving up.

“Being placed in remediation [in high school] may lead to student disengagement from schooling,” Ozek argued, adding that remediated high schoolers would be likely to miss out on potentially valuable and attractive career and technical courses. “At that level, because kids are able to leave school legally, it could increase rates of dropout,” he said.

The research also offers a fresh example of the limitations of test scores as a measure of success in school interventions. In a few other cases, most famously the federal Head Start preschool program, initial boosts to test performance have faded over time — only for the later life chances of participating children to be improved in other ways. Ozek said that “more and more evidence” had recently emerged suggesting that while assessment gains might prove transient, they also don’t tell the whole story.

“I believe it’s safe to say that even if you find test score effects that fade out, especially for middle and high school interventions, it’s too soon to reach conclusions about efficacy unless you take a look at long-term outcomes as well. It could be because test scores in middle school and high school may have lower predictability on adult outcomes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter