Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Charter schools in Boston, considered some of the strongest in the country, improve voter participation as well as academic outcomes like standardized test scores, according to a recently released study. The effects are significant in size and may be attributable to charters’ success in inculcating noncognitive skills, the authors find. But they are also driven entirely by gains among female students.

The study, circulated as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, represents the latest evidence pointing to some charters as institutions that strengthen civic engagement. A paper published last year that focused on North Carolina schools found lasting benefits to traditionally underserved students, including more frequent voting and reduced criminality, who attended a charter secondary school rather than a traditional public school.

And both echo the findings of a separate analysis of the civics-focused Democracy Prep charter schools. Graduates of the network, which operates over 20 schools across five states, were 12 percentage points more likely to vote in the 2016 presidential election than similar students, according to that study, and substantially more likely to be registered as voters.

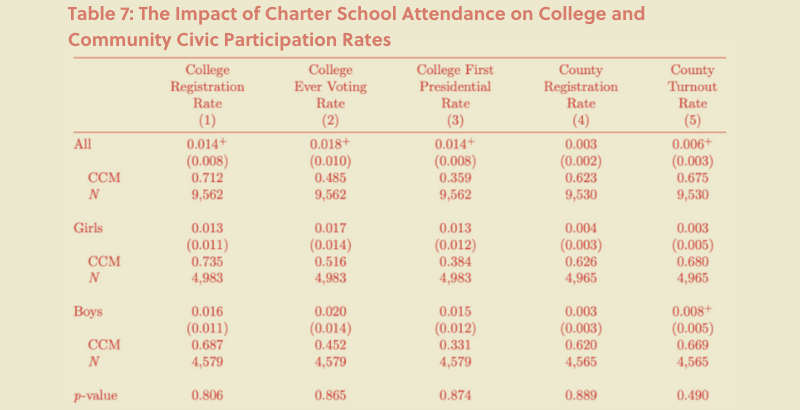

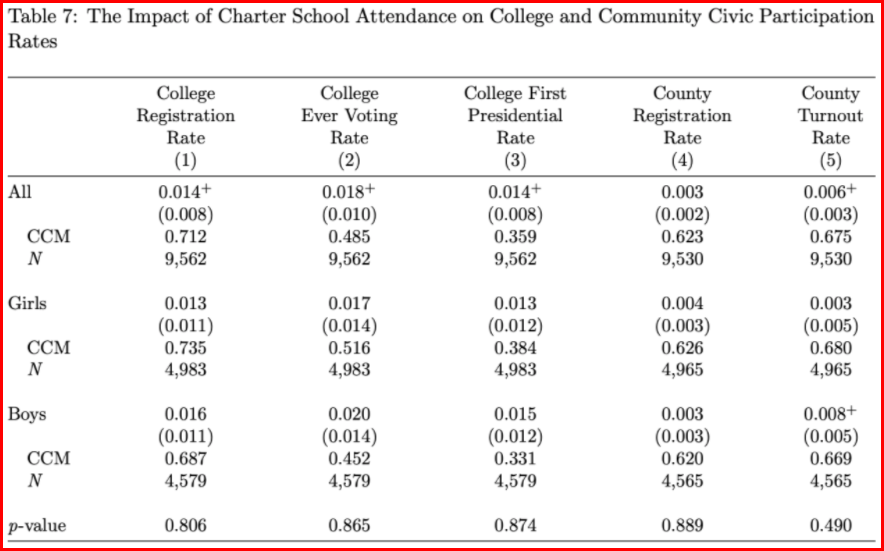

Sarah Cohodes, an economist at Columbia University’s Teachers College and a co-author of the Boston paper, noted that the voting effects she found were about half as large as those generated by Democracy Prep — six percentage points of increased voting likelihood, from a status quo of 35 percent — and that she measured no impact on registration. But a network like Democracy Prep, which persistently emphasizes civic participation and demands that students demonstrate mastery over multiple democratic skills, might be expected to lift voter participation, Cohodes added.

“This [research] is showing that even if you have a school where civics isn’t the mission, but you are still instilling more general skills — executive function, conscientiousness — alongside academic skills, that spills over into voting,” she said.

Cohodes and co-author James Feigenbaum, a professor of economics at Boston University, gathered student records from the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, along with lottery reports and voter records. The academic data included a battery of student demographic information, as well as performance metrics on state standardized tests, Advanced Placement course enrollment, SAT-taking, and college enrollment and persistence. Their sample included 12 Boston charters that enrolled students who were at least 18 years old at the time of the 2016 U.S. elections.

They then matched those records with Massachusetts voter files drawn from 2012, 2015, and 2018 (as well as files from nearby states New York, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Vermont, Rhode Island, and Maine, to account for out-of-state moves).

Like many other studies of charter school effectiveness, the analysis relies on the lottery mechanism that randomly assigns admissions to Boston’s heavily oversubscribed charter sector. Lottery “winners” (students who are ultimately enrolled in the charters) are broadly similar to lottery “losers” in terms of racial and ethnic background, socioeconomic status, and prior academic performance.

After comparing the two sets of data, the authors found that charter attendance increased students’ incidence of voting in their first presidential election after turning 18 by about 17 percent. That effect is particularly noteworthy because the study found that charter attendance did not seem to increase voter registration, often cited as one of the biggest procedural barriers preventing people from turning out on Election Day.

But within those results, an even more striking pattern emerged: The average increase in voting is the result of an especially large boost to female charter students — 12.5 percentage points — and no corresponding rise among males. That outcome generally mirrors broader patterns in U.S. voter distribution, which have increasingly shown females outvoting males in recent years.

To isolate a possible explanation for the gender split, the authors studied the various ways in which Boston charters affected their pupils compared with traditional public schools, including academic aptitude (measured through test scores), civic skills (measured through enrollment in an AP government or U.S. history class), and non-cognitive abilities (measured through school attendance and a student’s decision to take the SAT). Ultimately, the third category was the only realm in which a similar gender disparity existed, showing significant increases for girls compared with boys.

That detail is reminiscent of research conducted by political scientist John Holbein, who has found that high school students who are more likely to describe themselves as gritty are also more frequent voters. The link between non-cognitive skills like grit and persistence and voting propensity could be due to the obstacles that often stand in the way of filling out a ballot, Cohodes argued.

“You have to register, you have to find your polling place, you have to make your plan for getting there and getting off of work,” she said. “And then you actually have to show up and do it all. That involves persistence and follow-through, and…that’s where I see those schools coming in.”

It’s unclear whether charter schools in Boston are aiding the cultivation of such follow-through in female, but not male, students — or, perhaps, that they are burnishing those qualities in equal measure, but that boys begin school already far behind their female classmates. In either instance, Cohodes concluded, the findings provide more reason to think that the civic byproducts of charter schooling could be as consistent as their academic effects, which have largely been shown to be replicable across different settings and charter models.

“I do think it’s a different dimension of skill from academics, so it’s not necessarily the case that the schools that are bringing up test scores the most are also bringing up voting the most. But the things that Boston charters do are also things that KIPP schools do, that STRIVE charters and others do. So it’s not like it’s something that’s totally out of left field.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter