Change From the Bottom Up: Political Science Research Suggests That More CRT Bills Could Come to Washington Next Year

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The barrage of new state legislation aiming to control how teachers can talk about race and sex has become one of the biggest education stories of 2022. But new research on the connection between local and national political parties indicates that the laws could also become a Congressional fixture next year.

In a recently published article, political scientist Alex Garlick found that sudden increases in legislation at the state level are associated with more bills introduced in Congress on the same topic in the following legislative session. The correlation, which is particularly strong among Republican office holders and those within the same state delegation, suggests a consistent pathway of political messaging between state capitals and Washington, D.C.

Garlick, an assistant professor at the College of New Jersey, argued that anti-CRT proposals have already proven beneficial for some conservative lawmakers by driving press coverage and excitement among the GOP faithful. If Republicans win control over one or both houses of Congress in the midterm elections, as prognosticators expect, they will likely pass a similar piece of legislation — even though it would have “no chance” of being signed by President Biden, he added.

“By introducing these laws at the state level, Republicans are finding positive engagement with the media, their base, and donors,” Garlick said. “That indicates to me that we’re likely to see more of this at the congressional level.”

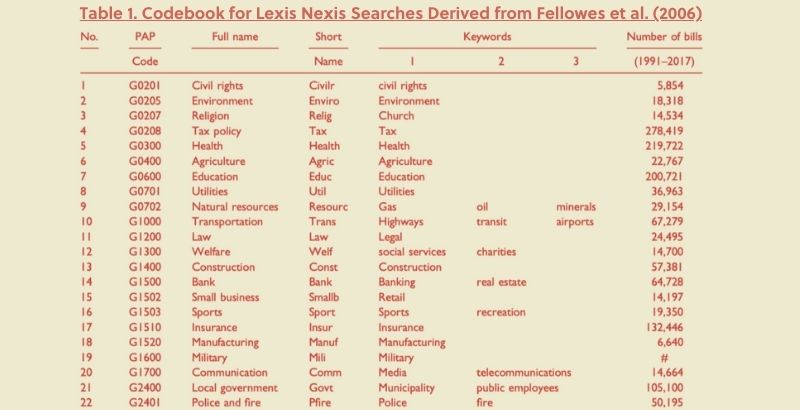

The study relies on an intensive examination of bills introduced in all 50 states and Congress between 1991 and 2016. Using a comprehensive index maintained by the data company LexisNexis, Garlick exported approximately one million citations of state and federal legislation, then grouped them into 22 separate policy areas. For each policy area, he tracked the timing of when bills were filed, irrespective of whether they were passed — first in statehouses, then in the next two-year session of Congress.

In 12 policy areas, including education, Garlick found that a marked increase in legislative attention at the state level tends to precede a similar increase at the national level. Specifically, an increase of less than two bills per state in any policy area would yield about five new bills in the next Congress.

Some evidence emerged suggesting a partisan dimension to the phenomenon, which Garlick calls “bottom-up diffusion.” By accessing information from civic data initiative Open States, which records the partisan affiliation of members introducing bills, Garlick found that between 2009 and 2016, Washington Republicans proposed more laws related to a given policy area after an increase in such bills proposed by state-level Republicans the previous session. Additionally, congressmen are more likely to take up the proposals of state representatives and senators within their own states.

For Garlick, political diffusion is a reflection of how state political organizations relate to their federal equivalents. In an era when most experts agree that the political and media environment is “nationalizing,” — with national debates around issues like racism and public health predominating over local concerns — bottom-up diffusion shows how lower-level actors can drive the conversation. Garlick likened the interaction to the way in which local fast food franchises implement menu or branding changes, but still mostly replicate the offerings of their parent company.

“You can see some experimentation at your local McDonald’s, but generally they’re serving the same thing,” he said. “For the Republican Party, what they’re serving is usually small government, tax cuts, etc. What’s been interesting in the past two years is how much education has moved into that basket of goods.”

According to Education Week’s ongoing tracker, lawmakers in over 40 states have introduced CRT-related bills just since last January. But they have been passed in just 14 of those states, while they have stalled, been vetoed, or remain under consideration in the rest. The relatively low rate of adoption, at least thus far, indicates that the attempts may be best understood as “messaging” legislation, aimed at appealing to interest groups and deliberately highlighting issues that are uncomfortable for the majority party.

National polling has split on the question of whether schools should be more tightly regulated in their efforts to teach students about controversies relating to gender, sex, and race. In the meantime, anti-CRT and curriculum transparency measures have already found sponsors among Republicans in Washington, suggesting that the national GOP will be prepared to take the baton — and, contingent upon majorities elected this fall, take votes — on K-12 legislation next year.

Garlick said that the explosion of new K-12 items on state agendas are indicative of two interlocking trends: both the “renewed interest in using education policy to reach ideological goals,” and the often stymied progress of new legislation in Washington. The rapid progression of school-related issues being addressed by legislatures, from COVID remediation to trans athletes to CRT, offer a guide to where politicians’ attention is turning.

“In this gridlocked, polarized reality of the last 20 years, Congress has really taken itself out of the game on a lot of major issues, so we need to look at other forces that are actually driving the political process. That’s why messaging legislation does matter, and why more attention needs to be paid to the states. Because that’s where politics is changing in a rapid way.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter