Study: When School Board Members Are Elected, Their Property Values Go Up

With the actions of school boards coming under increased scrutiny, a recently released paper offers a dark rationale for why some run to serve: Money

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

With the actions of school boards coming under increasing public scrutiny, a recently released study has offered a surprising window into the motivations of their members.

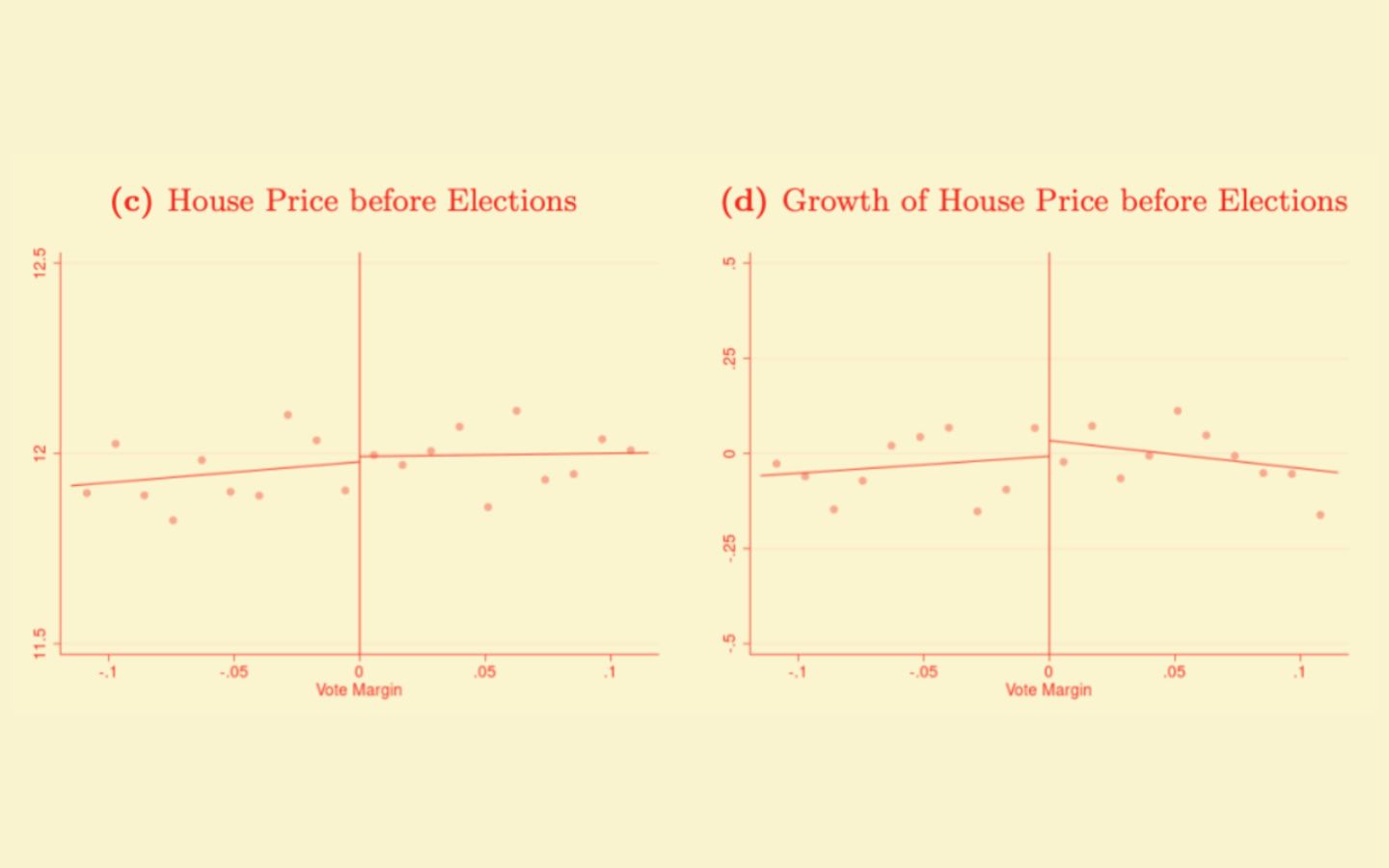

In a paper examining a decade of election outcomes, academics at the University of Rochester, the University of Colorado, and Duke University discovered that many winners of North Carolina school board races saw property values rise in their neighborhoods. The gains may have been generated by winners’ manipulation of attendance zones to sort whiter and higher-achieving students into nearby schools.

The findings also deliver an unmistakably partisan message: Board members registered as Republicans or independents yielded increases in home prices, while effects for Democratic winners were null.

“The finding that non-Democratic — but not Democratic — school board members affect local school attributes in ways that raise home prices in their neighborhood…raises the question of self-interested, as opposed to public service-oriented, motivations for seeking office,” the authors write.

The study’s design offers a somewhat dark perspective on the linkage between school quality and the cost of real estate, hinging on the often-controversial power of local education authorities to determine which schools in their district enroll which students. To derive a clear picture of board members’ potential unspoken agendas, it combines data from a host of sources and examines three phenomena at once.

First, the research team gathered a comprehensive set of election results from the North Carolina State Board of Elections, focusing on all school board races between 2006 and 2016. While the vast majority of those races were nonpartisan (as are most such races around the country) they were able to determine the partisanship of roughly two-thirds of all candidates by matching them to county-level voter registration rolls, which also provided identifying information on race, ethnicity, age, and home address.

Next they built an index of home values throughout North Carolina at the level of the Census block using records from ZTRAX, a database encompassing all home transactions in the state between 1995 and 2016. The inventory, maintained by the online real estate marketplace Zillow, tracked not just sales prices and addresses, but also design and construction details such as square footage, structural condition and number of bathrooms.

The combined figures clearly showed that property values in winning, non-Democratic candidates’ neighborhoods rose by an average of 4.2 percent — compared with the neighborhoods of losing non-Democrats — in the four years following a school board election. By comparison, winning Democratic board members enjoyed no bump in prices relative to losing Democratic candidates. Among winners registered as Republicans, who made up roughly 80 percent of non-Democratic candidates, the effects were even larger: a 6.2 percent increase in home prices relative to Republican losers.

“It could totally be possible that board members are increasing house prices across the whole district because they’re doing great things for schools,” said co-author John Singleton, a professor of economics at the University of Rochester. “What we’re showing in this paper, though, is that the distribution of those effects across neighborhoods is related to where school board members live. It’s about how the pie is being divided, and it looks like it’s being divided in a more equal fashion by Democratic candidates.”

Controversy over attendance zones

But what could explain the higher prices?

To answer that question, Singleton and his collaborators introduced a final set of facts: records from the North Carolina Education Research Data Center, which included academic, residential, and demographic information on students and schools. Soon enough, they found that the schools serving the neighborhoods of winning non-Democrats seemed to improve in the years following their election to school boards.

Specifically, math and reading scores on the North Carolina standardized End-of-Grade Tests increased slightly for children enrolled in those schools between kindergarten and the eighth grade. At the same time, average years of teacher experience (a crude but intuitive measure of school quality) increased significantly, with the proportion of brand-new teachers dropping by 12.8 percent and the proportion of teachers with over a decade of experience increasing by 3.8 percent.

Singleton said that the marked increase in teacher experience could be linked to lower turnover. Whatever the cause, it would be one of the clearest signals to potential home buyers — along with climbing overall test scores — of elevated school quality, which would in turn push home values higher.

“That’s something that’s potentially very visible to people who are deciding which neighborhood to live in and where to send their kids to school,” Singleton said. “But it’s also going to be private information that’s not more widely known — it travels by word of mouth through social networks: ‘This school is good, they retain their teachers.’”

But the perception of better academic performance seems to have more to do with changes in school composition than actual improvement. While overall standardized test performance in these schools trended upward, scores derived from teacher value-added — a measure derived by economists to isolate exactly what schools contribute to student learning — remained flat.

Instead, the ostensible academic growth may have been generated by changes in the schools students were assigned to. Those patterns in school assignment are substantially decided by board members, who may have a personal financial stake in having “good schools” (often, those that enroll more advantaged students who are most prepared to succeed academically) located near their own homes.

The process of drawing and redrawing school attendance zones is typically highly controversial for that reason. In recent decades, some education analysts have advocated the intentional construction of attendance zones that cultivate more racial and socioeconomic diversity in classrooms. Efforts to put such plans into action have sometimes been stymied by changing election results — including in Wake County, North Carolina’s largest school district, where voters have reacted harshly to an ambitious desegregation plan.

Singleton and his colleagues found that in the years after local non-Democrats won election to school boards, the schools serving their neighborhoods became 3.5 percent whiter relative to those serving the neighborhoods of non-Democratic election losers; enrollment of high-achieving students (those scoring higher on state exams than same-aged children the previous year) increased by 3.6 percent. No such changes were detected among schools serving the neighborhoods of winning Democrats.

The authors also revealed that, compared with results measured in the year before an election, average test scores markedly increased in the schools enrolling children who lived in the same Census block as a winning, non-Democratic school board candidate; in other words, local kids were being assigned to higher-performing schools after their neighbor became a board member.

Eric Brunner, an economist at the University of Connecticut, said that factors like test scores operated as clear signals in real estate markets because of the “very limited information” that families can otherwise access. Previous research has shown that the school ratings included in sites like Zillow can lead directly to neighborhood segregation.

“What buyers are given by their realtors, and the research they do themselves, is typically the average test scores in different school zones,” Brunner argued. “If [board members] were able to adjust test scores within the boundaries of the school zone such that they went up on average — even though students weren’t smarter, and it was just due to sorting — then home values will go up. People think it’s a better product.”

‘Normal people engaging in politics’

Brunner noted that the study builds on previously released research by Singleton and another co-author, economist Hugh McCartney, which found that Democratic school board members in North Carolina tended to reduce school segregation by shifting school assignments. The latest paper takes that insight “one step further,” he said, by demonstrating the self-dealing that might follow from the massaging of attendance zones.

He also took note of an interesting sub-finding of the newer study: The changes in school-level achievement and home values were driven not only by non-Democrats, but also by candidates elected on an at-large basis to represent an entire school district.

At-large contests only made up about one-quarter of board races in North Carolina over the course of the study, but their structure could help explain its results, Brunner said. Marginal changes to school attendance zones would theoretically produce a small number of winners, but also some “losers”: those who live near a board member but see themselves as adversely impacted by school assignment changes.. Under new assignment patterns, such voters might see their own property values fall as their children are enrolled at relatively lower-achieving schools.

That kind of dissatisfaction would be a serious liability in a ward-based race, Brunner observed; but if the candidate was elected on an at-large basis, most of their voters would take no notice of minor assignment changes occurring in other parts of their school district.

“If you’re elected at large, you could do something that satisfies a very small, unique group of people without pissing off the other voters within your ward. You don’t need to be worried about satisfying the rest of your ward — you could satisfy a microcosm of it.”

Robert Maranto is a political scientist at the University of Arkansas’s Department of Education Reform. Between 2015 and 2020, he also held a seat on the Fayetteville School Board, which undertook several rounds of student redistricting during his tenure. Maranto noted that such policy changes were some of the most fraught he could remember, recollecting in an interview that certain constituents needed to be “grandfathered in” to attendance zones viewed as superior.

“When people buy a house, or sometimes even an apartment, they have the expectation that their kid will go to a certain school,” Maranto said. “So if you upend that expectation, it can be very controversial. Even if they’re redistricted to a brand-new school, people are usually not happy about that.”

He added that the magnitude and direction of the effects measured by Singleton and his collaborators was “very plausible,” but added that his own interpretation was “somewhat less nefarious” than what others might infer.

“Your constituents either want or, more often, don’t want boundary changes,” he said. “It could be for elitist purposes — ‘We don’t want our kids going to school with those kids’ — but you’re representing that on the board. For me, it seems more like normal people engaging in politics.”

Singleton himself added that he would like to see similar research conducted in other states to reveal more about the connection between district leadership, school outcomes, and home prices. Though the findings from North Carolina were suggestive, he noted, the “very distinctive flavor” of local politics — including a comparative abundance of private and charter schools, which could dilute the effects somewhat by partially de-linking home addresses from school assignment — meant that a similar experiment might yield different results elsewhere.

Above all, he said, it was important to further explore the role of school boards as actors in a complex machinery of school governance because the difference between a good board and a bad one might be greater than is now understood.

“I think there’s mounting evidence that boards can be consequential players. And we’re just starting to learn more about the conditions under which these kinds of effects can arise.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter