The ‘Mass Exodus’ of Teachers Never Happened, Paper Argues

Clouded by inconsistent data, the concern about shortages is inflated, according to research revealing that turnover actually decreased in early 2020

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

While pundits caution that schools are facing catastrophic teacher shortages — the result of substantial exit from the profession during the chaos of COVID — new research indicates that those warnings could be overstated.

Teacher turnover rates are actually about the same as they were before the pandemic, according to a working paper released this month through the Annenberg Institute at Brown University. Flush with pandemic relief money and faced with the generational challenge of fostering learning recovery, school districts are hiring for more positions and leaving vacancies open for longer.

A wide-ranging analysis of employment trends from national and state-level sources, the brief does confirm that the K-12 workforce shrank significantly after the onset of COVID-19 and its disruptions to schooling. After roughly a half-decade of steady growth, total public school jobs decreased by roughly 9% through May 2020. The initial drop represented more than twice the number of positions erased during the financial crisis of 2008.

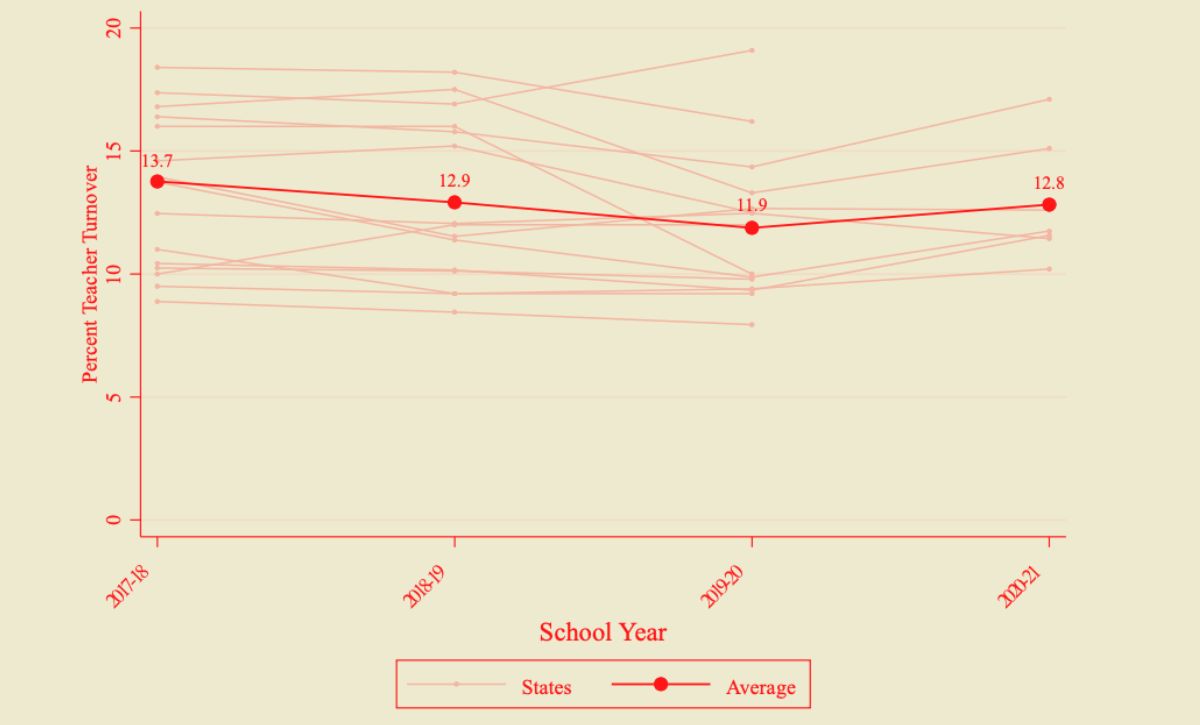

But the data also suggested that those positions were disproportionately cut from non-teaching ranks. Occupational records from both national and state sources showed measured declines among nurses, administrative support staff, paraprofessionals and other predominantly non-instructional employees. Across all the states included in the study, there was actually generally less teacher turnover during the summer of 2020 — likely the residue of that year’s severe economic slowdown, which discouraged many from leaving their jobs. (During the summer of 2021, seven of those states saw an average turnover increase of 1.2 percentage points, effectively bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels.)

Confusion about the state of the education field has emerged due to a lack of consistently reported data on millions of school employees, the authors argue. In fact, the report was only made possible by combining several overlapping federal data sets — each with its own liabilities — with additional findings from 16 states that publicly reported annual statistics on turnover through the first year of the pandemic.

Matthew Kraft, a Brown economist and the paper’s lead author, said he was “very concerned” about the increased burnout teachers reported experiencing over the last few years. While a true mass exodus of educators hasn’t yet occurred, Kraft said that profession-wide exhaustion could someday trigger one. But he added that short-term instability in the education workforce has “obfuscated” longer-term issues of working conditions and public funding that demand more thorough examination.

“There’s no doubt that this story [of educator dissatisfaction and turnover] is catching our national attention, and it’s generating headlines,” Kraft said. “The problem is that most of those stories are asking a question for which there is a nuanced response, and nuance isn’t communicated effectively in our sound-bite world.”

Kraft and his co-author, Joshua Bleiberg, culled figures from four surveys conducted by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, each collecting regular reports from tens or hundreds of thousands of employers in both the private and public sectors. That information allowed them to not only generate month-by-month estimates of the total number of elementary and secondary education jobs, but also form a clearer view of the large swings in hirings, resignations and layoffs between March 2020 and May 2022.

The pair supplemented that picture with files from 16 state education agencies — though these additions were complicated by the states’ differing definitions of turnover. For the purposes of their study, Kraft and Bleiberg described it as the percentage of teachers in one school year who did not return to the same school or district in the next year.

One possible explanation for the vacancies that did linger was a period of weak job growth after schools were closed in spring 2020. According to one federal survey, K-12 and higher education institutions collectively hired 32,000 fewer educators per month over the first six months of the pandemic. That belt-tightening was likely caused by worries that the austerity measures of the last global economic downturn would be repeated, Kraft remarked.

“We had lived through the lessons of the Great Recession, which substantially cut education funding over multiple years and led to hundreds of thousands of teachers being laid off,” he said. “So schools were cautious, and I think rightly so, about filling positions even from natural turnover.”

After the slashed budgets of the 2010s, few if any observers predicted the federal government would allocate nearly $200 billion in pandemic relief to American schools. If that understandable misapprehension guided decisions during the early phases of the crisis, a general absence of accurate, real-time data has further clouded the picture ever since.

The deficiencies of public data sources are several, Kraft and Bleiberg note. Some surveys don’t clearly differentiate among K-12 employees, such that job additions or attrition among non-instructional staff can be conflated with those affecting teachers. Others make it hard to differentiate between public K-12 schools and private institutions (or even colleges and universities). And as with virtually all data regularly collected by the government, figures are subject to serious revisions even months after their initial publication.

Chad Aldeman is the policy director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, a research group that studies education finance. In an email to The 74, Aldeman called national teacher employment data “at best a patchwork quilt of federal, state and local databases, much of it several years old.” That disorganization makes it difficult to answer even basic questions, such as how many job openings exist throughout the nation’s K-12 schools and which specific positions principals and superintendents are hiring.

In normal circumstances, that kind of opacity paves the way to misguided policy choices. But at a time of unprecedented tumult in the labor market, it might come at the cost of critical, one-time resources that could otherwise be spent helping students climb back from years of lost learning. Aldeman said he was aware of cases in which districts were poaching from their neighbors, or even cannibalizing their own workforce, to fill specialist roles.

“I don’t think state and federal policymakers are taking these data gaps seriously,” he wrote. “Instead, states seem to be spending their own money blindly, and I don’t see many thoughtful plans to track the spending alongside student outcomes to make sure the increased staffing levels actually translate into better services for students.”

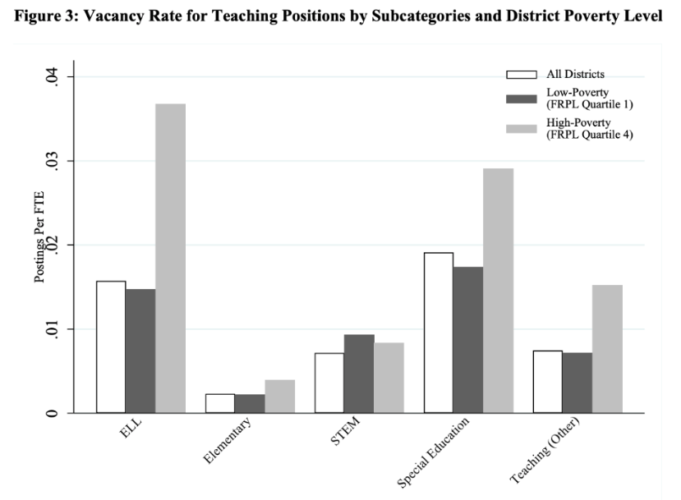

Kraft said that public confusion over the nature of teacher shortages is a serious concern, pointing to previous evidence showing higher vacancy rates at high-poverty or predominantly minority schools. The difficulties those schools face in hiring, and the increased stress suffered by their staff, are persistent problems that call out redress through higher pay and better working conditions, he argued; misbegotten narratives based on incomplete information could only make them harder to solve.

“We are failing these communities by failing to understand the nature of the problem, Kraft said. “And by failing to understand the nature of the problem, we may well diagnose it incorrectly and prescribe remedies that fail to address the underlying, structural inequities.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter