Research: Achievement Shows Signs of Improvement, but Youngest Kids Need Help

Slow-moving rebound aided by mild summer slide, ‘buoyancy’ of students’ skills as schools emerge from pandemic

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Researchers saw promising signs of a slow-moving rebound in student achievement this fall, more than a year after a dire spring where performance “bottomed out.”

As U.S. students in August and September began their fourth school year under the shroud of COVID-19, researchers from NWEA, the nonprofit behind the widely used MAP Growth assessment, took an early look at their achievement. The data suggest that gaps between pre- and post-pandemic performance have been slowly shrinking.

Among the biggest contributors, for reasons researchers don’t quite understand: In 2022, the typical “summer slide” didn’t slide quite as much, giving kids a small advantage as the school year began.

The new findings are “evidence of resiliency on the part of students,” said Karyn Lewis, director of NWEA’s Center for School and Progress. “I think we’re seeing some buoyancy in terms of students’ achievement levels. That’s a testament to simply getting back in the classroom, being reconnected to their peers and their teachers.”

But in a more sobering finding, NWEA found that the youngest students in the study — third-graders who were kindergarteners when the pandemic closed their schools — showed the largest reading achievement gaps and the least “rebounding” from previous tests.

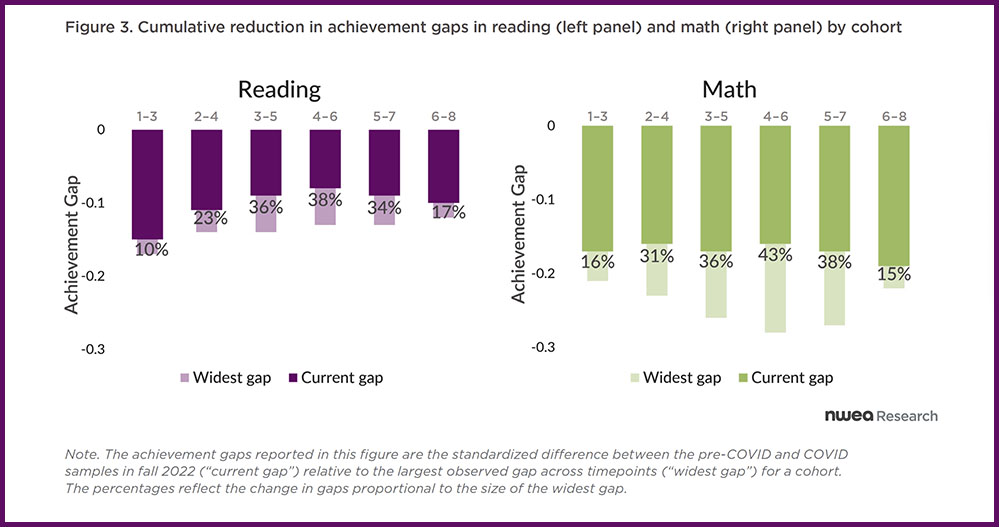

In reading, third-graders reduced their widest achievement gaps by just 10%, far less than other groups. By contrast, sixth-graders’ gaps shrank by 38%. The research found similarly small reductions for third-graders in math.

“That suggests to me it was really detrimental for those kiddos to be doing Zoom school in kindergarten to pick up on some of those foundational reading skills,” said Lewis. “And then for kids that return to the classroom in first grade, imagine trying to learn phonics with your teacher wearing a mask.”

These young students’ reading improvement was slower than their math improvement, researchers found. And they estimate that it will take them at least five years to fully recover from the pandemic in both reading and math, longer than nearly any other group studied except current eighth-graders. Given the five-year time horizon, many of those students may never fully get up to speed in either subject by the time they finish high school, they warn.

The new findings add to data NWEA released last month that showed achievement losses in the 2021-2022 school year disproportionately affected low-performing students, whose skills have languished since the pandemic, unlike that of high-performing students. At the time, Lewis told The 74, “If we think of the range of test scores, we see that the ceiling has remained stable. But the bottom has dropped out.”

Meanwhile, the new study found, the highest-performing 10% actually made more progress toward academic mastery than would have been expected absent COVID.

“In study after study we are seeing clear evidence that while some students are getting back on track quickly, far too many are not,” said Robin Lake of the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) at Arizona State University. “We’re also seeing clear evidence that schools and districts are really struggling to meet student needs.”

Federal ESSER funds, slated to help schools recover from the pandemic, are due to run out over the next three years — and schools must figure out how they’re going to spend the money by September 2024.

“I think this is a group we really need to keep our eye on and make sure that elementary teachers that are serving them now actually know how to help them catch up,” NWEA’s Lewis said. “You can imagine the trickle-down effect it has if these kids continue to struggle in reading.”

In addition to hurting students who had just transitioned to kindergarten, the pandemic deeply affected those who were even younger — from newborns to four-year olds, said Michelle Kang, CEO of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. As they prepare for elementary school, those students are going to need supportive teachers, she added, who “help them build on their resilience and thrive in academic and social emotional contexts.”

W. Steven Barnett, senior co-director and founder of the National Institute for Early Education Research, said it makes sense that the youngest students have struggled in reading. “If you think about where kids learn math and reading, the home environment has a bigger impact on reading than math. So the extent to which the home environment was also negatively impacted by the pandemic, you’d expect that to have a bigger impact on reading, a bigger impact on younger kids.”

While he’s encouraged by the summer findings, Barnett noted that a lot of federal COVID relief funding remains unspent, so it’s difficult to draw a direct line between federal aid and improvements in achievement. But he said schools should not waste time figuring out how to spend their relief money going forward, whether it’s for summer programs or intensive tutoring. “There are a bunch of tutoring programs that have been proven highly effective that schools could adopt that identify the kids who are behind,” he said.

A number of programs offer one-on-one instruction and don’t require licensed teachers for implementation. Actually, Barnett said, they offer training for volunteer and paraprofessional tutors. He also suggested that student-teachers could step in to fill a tutoring void in a tight teacher labor market.

CRPE’s Lake said the new data suggests one clear conclusion: “Now is the time to shift course. We must start acting like this is a national emergency and bring new solutions to the table. We cannot continue to ignore the mounting evidence that we are failing to give this generation of students a solid foundation for the future.”

A ‘dampened’ summer slide

NWEA’s Lewis said the overall upward progress among the students studied is in part due to what she called a “less-worse slide” over the summer, compared to typical years.

And while it might seem logical to attribute that progress to intensive, ESSER-supported summer learning efforts, like Barnett, Lewis cautioned against trying to find “a thread of causality” in the findings.

Actually, she said, other research suggests that many of the available summer remediation efforts “were probably not taken advantage of to the extent that would really lead to the results that we’re seeing here.”

But Lewis said it’s important to put both the progress and challenges in perspective. Those who would call the nation’s third-graders “a lost generation” — as well as those who don’t think the ongoing gaps are a big deal — are both missing the larger point.

“Like most things, I think somewhere in the middle is where we need to find ourselves,” she said. What may be most important is “shining light on which kids have been harmed the most” and serving them in a less standardized, more personalized way — for instance, through a “layered approach” to tutoring, summer programming, and other strategies.

“There will be no silver bullet,” Lewis said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter