Suicide, Alcohol and Drugs Drove Deaths for Those Without a B.A. Prior to COVID

One positive: While mortality rates used to be similar for Black men with or without a college degree, those with a bachelor’s now faring much better

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Princeton researchers found a rise in pain and deaths of despair — suicide, alcohol abuse and drug overdoses — fell much heavier on those without a bachelor’s degree than on those who finished college in the decade leading up to the pandemic.

Building upon their earlier blockbuster findings on the link between education and mortality, the researchers said Americans are on two distinct paths based on educational attainment. Angus Deaton, who co-wrote the recently published The Great Divide: Education, Despair, and Death with Anne Case, calls the current system unfair.

“The B.A. has become this sort of condition for participation and dignity in the modern economy — and a lot of it is unnecessary,” Deaton, a British American economist and 2015 Nobel Prize winner, told The 74.

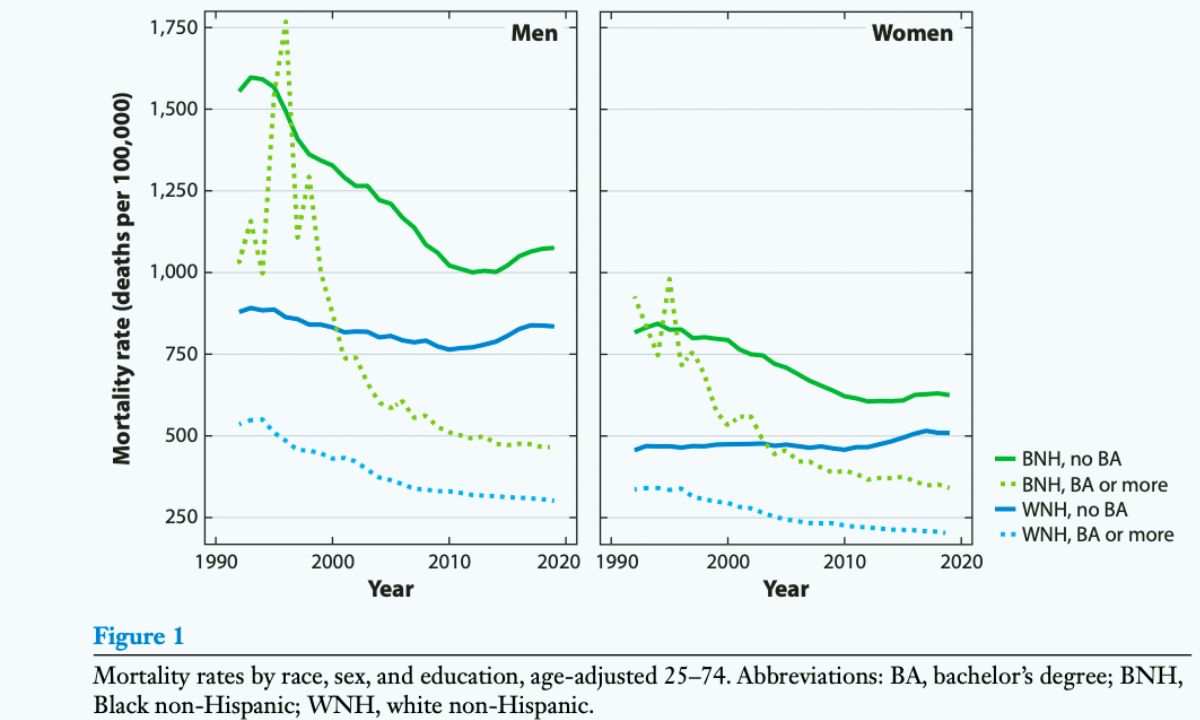

There was, however, one positive development, the researchers said. While the gap in mortality rates between those with and without a bachelor’s grew markedly since 1990, Black men with four-year degrees fare better than they ever have since such data became available more than three decades ago.

“It used to be that Black mortality rates were not very different whether you had a B.A. or not,” Deaton said. “Now, Black men with a B.A. are much closer to white men with a B.A. than they are to Black or white men without a B.A. The same is true for [Black] women. Blacks with a B.A. have made a huge amount of progress.”

But inequity remains: While 42% of white Americans 25 and older earned a bachelor’s degree, just 28% of Black Americans and 20% of Hispanics have this advantage, according to recent census data.

“The B.A. divide is getting bigger while the race divide is getting smaller — but it still exists,” Deaton said.

The pandemic worsened academic outcomes, particularly for minority men. While undergraduate college enrollment dropped for all students, for example, the figures are startling for Black men: They fell by 14.8% overall and by 23.5% for those enrolled in two-year schools between 2019 and 2021, research shows.

Latino men also fared poorly during this time, with their enrollment slipping by 10.3% overall and by 19.7% among those attending community college.

And COVID’s toll expanded well beyond education: Life expectancy itself fell in the U.S. in 2021 for the second year in a row, the first time it dropped for two consecutive years in a century, NPR reported.

Deaton’s and Case’s work has focused specifically on how higher education has acted to ward off death from a particular type of suffering, calling it a “talisman” against overdose fatalities.

The death rate from drugs, alcohol and suicide climbed for all Americans in the most recently studied period, they found, but was concentrated among those without a bachelor’s degree: The alcohol-related mortality rate for whites without a bachelor’s degree increased by 41% between 2013 and 2019 for those ages 25–74. The suicide rate jumped by 17%, and the drug-related mortality rate shot up a whopping 73% for that group, researchers said.

Results were equally troubling for Blacks and Hispanics who did not hold a bachelor’s degree: Drug-related deaths more than doubled between 2013 and 2019 for these two groups. The suicide rate increased by a third for both. Alcohol-related mortality rates rose 30% for Blacks and by 24% for Hispanics who hadn’t completed college.

The researchers gleaned data about educational attainment, age, sex, race, ethnicity and cause of death through death certificates. They called out how fentanyl, the drug now dominating headlines, had vastly different impacts in the Black community depending on education.

“The arrival of street fentanyl in 2013 led to a drug mortality rate among less-educated Blacks that was seven times greater than that among more-educated Blacks in 2019,” they write.

Deaton said results were not much improved for those Americans who completed some college — including those who earned an associate’s degree. Their mortality and disease rates and job placement were just slightly improved but far closer to those with a high school education than those with a bachelor’s degree.

While the calculations, first published in Annual Reviews in August, were made before data from the pandemic became available, there was no reason, researchers said, to think the rates would decline once COVID-19 was brought under control.

Deaton’s and Case’s earlier work grabbed so much attention after it identified that mortality rates among middle-aged whites shot up in a relatively short amount of time, between 1999 and 2013, because of suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol abuse. From this finding, they coined the much-quoted term “deaths of despair”.

Back then, the authors linked the deaths of less-educated white Americans to economic and social conditions. Through their later work on their 2020 book, they cited falling real wages, a decline in religious participation, increasing rates of children born to unwed mothers and a drop in marriage rates overall.

A decrease in availability of good jobs for those without a bachelor’s degree, exorbitant health care costs and a lack of a financial safety net for those who were neither children nor elderly also contributed to a “rising tide of despair,” they said.

“Both the safety net and the financing of health care are radically different in other rich countries where — with a few exceptions — there are few deaths of despair,” they noted.

Under these circumstances, they wrote, it was not surprising to see a rise in drug and alcohol abuse, unhealthy eating and suicide.

“We do not believe that the opioid epidemic in the United States would have happened to the extent that it did without the ocean of pain and distress among less-educated Americans,” they wrote.

Deaton told The 74 their later research yielded two important findings.

“These deaths of despair, which were largely confined to whites, later spread to the African- American and Hispanic population, largely to do with drugs, both legal and illegal, including fentanyl,” he said. “The other is that these deaths of despair are not confined to whites currently in middle age, but are even worse among younger people: Each younger-born generation is getting worse than the one before. We know a lot of people who have fallen into addiction traps. Among people without B.A.s, this is much worse.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter