Holding Back Struggling Readers Helps Them — and Their Siblings — Study Finds

The research is the latest pointing to big benefits from third-grade retention policies. But it’s unclear how such gains are achieved.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Holding back struggling readers in elementary school can yield benefits that extend in surprising directions, a recently released study suggests. In addition to improving academic performance for targeted students, the authors determine that younger siblings in the same families also see greater success in school in subsequent years.

The study, circulated as a working paper through the National Bureau of Economic Research, focuses on a Florida policy that has previously been shown to boost achievement among young learners. In so doing, it adds a new wrinkle to an evidence base that has not only expanded substantially over the last few years, but also coalesced around a consistent discovery: grade retention, at least for low-scoring children in early grades, meaningfully improves their test scores.

How that improvement is accomplished is still up for debate. While some believe schools foster the learning gains through extra instruction, others point to the simple advantages of children studying the same material after undergoing a year of cognitive and social development. And the latest results — referred to as “spillover effects” on younger brothers and sisters — raise further questions as to how retention works.

Umut Özek, a senior economist at the RAND Corporation and co-author of the latest Florida paper, said that while the academic growth he measured was likely attributable to multiple causes, families and educators could be motivated by the “threat effect” of students being flagged to repeat a grade.

“When you have this goal set in third grade, such that you need to score above a certain level to be promoted, it provides a clear signal to schools and parents that they need to do something in earlier grades so their students aren’t retained,” he remarked.

However promising the research outcomes, grade retention remains one of the most contentious planks of the education reform agenda. Since 2013, over two dozen states have passed laws either allowing or requiring school districts to make grade promotion decisions based on elementary reading performance. But parents have increasingly expressed frustration with the policy, with some suing for the right to opt-out of third-grade reading exams. Legislators in Michigan and Ohio significantly relaxed their elementary reading mandates earlier this year. In Tennessee, which adopted its own retention policy in 2021, 60 percent of third graders scored below the threshold for promotion this spring, and over 25,000 retook the exam in an effort to demonstrate proficiency.

In the wake of generational learning loss stemming from COVID-related school closures, some experts expect retention to gradually affect larger numbers of K–12 students. Katharine Strunk, the dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, said that the prospect of seeing their children fall short of promotion was having an “eye-opening effect” on many families.

“One thing that’s come out of the pandemic is that we know that parents are not always made aware of the challenges facing their kids at school,” Strunk said. “Maybe for the first time, parents are being told, ‘Your kid is really struggling in a way that’s much worse than his or her peers.’”

A ‘very clear signal’ for parents

Florida’s reading retention law, first enacted in 2002 under then-Gov. Jeb Bush, requires pupils to score above the minimum achievement level on a literacy exam in order to move onto the third grade — though “good-cause” exemptions are often granted to children who receive special education or English learner services, who have already been held back, or who can demonstrate reading proficiency via other means. Due in part to energetic lobbying from Bush and his think tank, ExcelinEd, a slew of other states adopted similar proposals over the last decade.

To reveal the impact of the original policy, Ozek and his collaborators gathered a comprehensive set of student-level data from 12 anonymous school districts, including standardized test scores, special education status, demographic indicators and teacher characteristics. That information was combined with birth records from the same areas, allowing the researchers to link the progress of older students targeted for retention with that of their closest younger siblings.

The paper encompasses the first seven years of the state’s grade retention system and subsequent test scores for both older and younger siblings through 2011–12; during that period, Florida’s portion of third graders retained was approximately 10 percent, though the annual rate declined from 15 percent in 2002 to just 6 percent in 2010.

Comparing kids who placed below the retention cutoff score against those who placed above it, the team found that repeating the third grade was associated with a statistically significant increase in state test scores in both reading and math. That finding largely echoes those of prior research into retention in Florida, including an earlier study co-authored by Ozek.

To account for the growth, Ozek cited the breadth of resources that schools are required to provide children who are not promoted. Such students are assigned to highly effective teachers, receive 90 minutes of dedicated reading instruction each day and are given the option of attending an intensive, literacy-oriented summer camp.

“These students receive substantial support in the following year, and that support is more personalized and tailored toward their needs,” Ozek said. “That’s probably a key element behind the success of some of these policies.”

That observation echoes the conclusions of a paper circulated this spring by a pair of researchers at Michigan State University. Their analysis, which examined the effects of early literacy policies on both state test scores and performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, showed that achievement growth was greatest in states that implemented “comprehensive” policies — including some form of retention, but also extensive assistance for affected students and coaching for their teachers.

“Altogether, these results indicate that the full set of interventions available under early literacy policies is important in improving literacy achievement and skills,” the authors wrote. (Strunk, until recently an education professor at Michigan State, helped review the paper.)

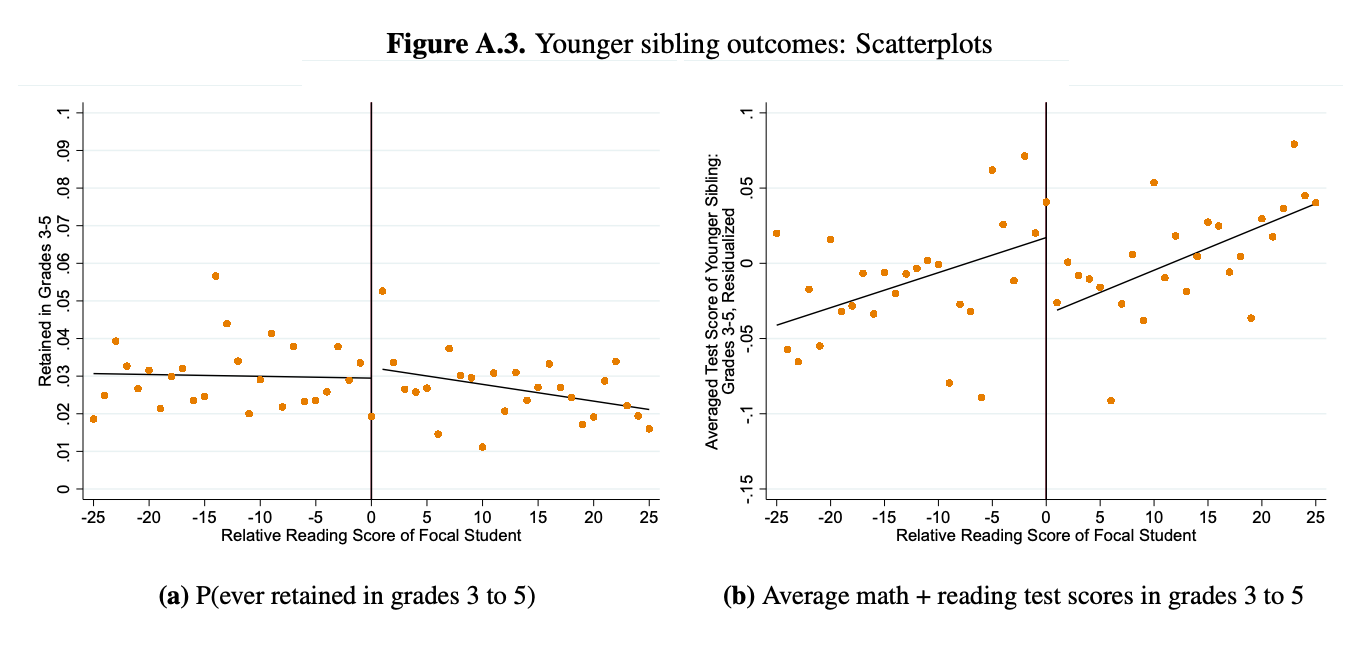

Beyond the direct improvements, however, Ozek’s Florida paper finds that retained students’ younger siblings also saw a bump in test scores compared with the brothers and sisters of children who were promoted to the fourth grade. That advancement was measured at approximately 30 percent the size of the main effects; it was also particularly concentrated among boys, as well as immigrant families and those including a disabled child.

The authors offer several theories to explain why younger siblings experienced positive, albeit smaller, movement. Among them: Having an older sibling held back was correlated with being assigned to a classroom with relatively higher-performing peers, perhaps because parents of retained third-graders influenced the classroom placements of their younger children.

Additionally, in instances where retained students attended schools that received a state accountability score lower than an A over the preceding two years, their parents were more likely to move younger siblings to schools with better reading results, higher-performing teachers (as measured by value-added scores on state tests) and those specializing in reading instruction.

Ozek said he could understand why having a child repeat a grade would seize parents’ attention. A father of two, he noted that retention was a much starker message than performance on state tests, and one that would likely cause adults to take notice.

“It’s really hard for me, even as an education policy researcher, to assess what those [state test] scores mean,” he said. “But when you get a signal that says, ‘Your kid is not performing at a level that will allow them to be promoted to fourth grade,’ that’s a very clear signal that will likely induce a response from parents, and schools as well.”

The harms of being held back

Little outside evidence exists to either validate or undermine the new study’s claims around spillover effects on younger family members. But competing explanations have recently cast doubt on the fairness and effectiveness of retention in early grades.

Mississippi’s third-grade “reading gate,” which largely resembles Florida’s law, has been nationally lauded for pushing up historically dismal literacy scores over the last decade. At the same time, some policy observers argue that much of that climb is due to a form of statistical sleight of hand; since a healthy portion of the state’s fourth-graders have been held back, their additional year of intellectual maturity — not the effects of retention and supplemental instruction — could be responsible for their progress. (Advocates have responded that while that claim may be applicable elsewhere, it is dubious in the case of Mississippi, where the “reading gate” appears not to have increased the average age of fourth graders.)

Meanwhile, studies of students retained in higher grades have found that being held back in middle or high school makes students less likely to graduate and significantly more likely to be convicted of a crime. While younger children are seemingly less fazed by repeating a year, the practice may be salient, and damaging, when it coincides with transitions to middle and high school.

The University of Pennsylvania’s Strunk, who has investigated some of the effects of Michigan’s now-weakened retention system, agreed that students who repeated third grade had “more opportunity to develop and learn,” theoretically allowing them to achieve at higher levels on that basis alone. Beyond that possibility, she added, there is something of a paradox in sending low-achieving students back to the same classrooms and teachers that failed them the first time around.

“Is it really a good idea to give kids an extra year of school if the schooling is not working the way we want it to?” Strunk wondered. “It’s like the Einstein quote: ‘The definition of crazy is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.’”

Leaving aside the precise causes of post-retention growth, however, the bulk of the recent research suggests that retaining floundering readers can produce notable short- and medium-term gains. Another recent study of a Florida-style literacy standard, focused on schools in Indiana, showed that third graders who scored just below the threshold for promotion ended up significantly out-performing their classmates who were narrowly promoted. Those effects extended into the middle school grades, with no sign that retention increased disciplinary or attendance problems.

Cory Koedel, a co-author of that study and an economics professor at the University of Missouri, said he was agnostic about which explanation for the progress mattered most, or even whether the effects would eventually fade out.

“In my view, whether it’s the extra year of instruction or the extra year of maturity that’s allowing them to catch up isn’t that important. What’s important is that they’re catching up.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter